Despite military conscription ending in 1973, the prospect of being drafted was a scenario on the minds of many gay men in the decades following the Vietnam War. In 1980, as a response to Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan, President Jimmy Carter reinstated the system that required all men born in 1960 or later to register for the Selective Service within 30 days of their 18th birthday. This kicked off the fear of another military draft.

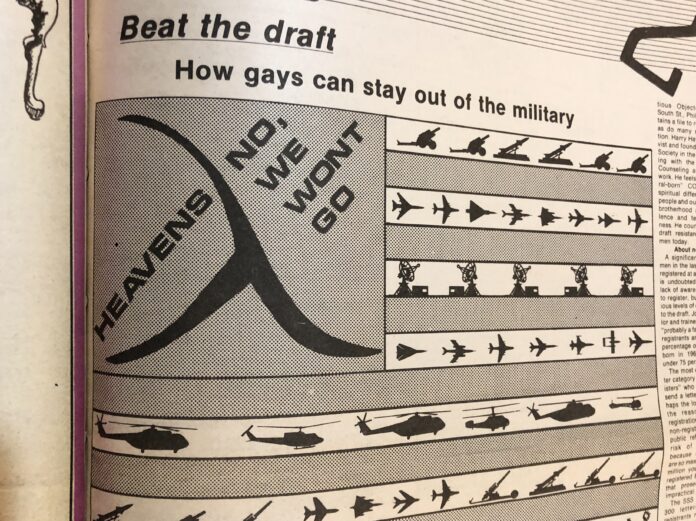

In October 1981, PGN published a feature titled “Beat the draft: How gays can stay out of the military,” by Marc Killinger.

“Not only do military regulations prohibit homosexuality while in the armed forces, it prohibits anyone who knows they are gay from entering in the first place,” Killinger wrote. “Hence, young gay men who are drafted face a double jeopardy of prohibitions.”

At the time, there was debate over whether or not the all-volunteer military was sufficient. When President Carter reinstated the Selective Service System, it ignited new theories that a draft was imminent. Senator Mark Hatfield (R-OR), who opposed the Vietnam War, was quoted as saying “If we had not had the draft, we would never have been at war for the length of time we were in Vietnam.” Michael Mongeau, who worked for the Friends Peace Committee, also felt that “they’re getting ready, but doing everything they can without taking politically unpopular actions.”

With the fear of another draft on the horizon, many gay men believed that if they were drafted they could merely proclaim their homosexuality and not be forced to serve because they were “medically exempt.” However, this option turned out to be much more complicated and potentially problematic than people realized. As Killinger wrote:

“Announcing that one is ineligible for the military because of homosexuality means taking the risk that permanent military records are not used against one later, either for the job and career discrimination we are routinely subjected to, or else in the context of some far worse anti-gay crackdown.”

However, there were other options to avoid being drafted than seeking a medical exemption. One could choose not to register for the Selective Service at all (it was estimated that “close to one million eligible registrants will not have registered” by the end of 1981). However, this option left one open to prosecution, though it was unlikely given the sheer volume of non-registrants. During the Vietnam War, an estimated 250,000 men refused to register, and around 250 of them were ultimately convicted.

Another option was to register as a “conscientious objector” (CO), someone who opposes war in any form “for religious, moral, or ethical reasons.” The Selective Service Board Member Information Booklet, when describing a conscientious objector, stated that “the fundamental issues are the sincerity with which his beliefs are held, the depth of his convictions, and the fact that his conscience would give him no rest or peace should he participate in war.”

Registering as a CO was deemed as the best path for draft resistance by longtime gay rights activist Harry Hay, who founded the Mattachine Society in the 1950s. During the ‘80s, Hay worked with the Lesbian/Gay Draft Counseling and Resistance Network. Hay felt strongly that registering as a CO was a safer choice than seeking a medical exemption. In fact, so many men had sought a medical exemption due to homosexuality in the 1960s that it was taken off of the Medical History Form, and there were no strict guidelines in place that would make one eligible for the medical exemption. Hay was especially offended at the idea of “proving” one’s gayness through letters from friends or a psychiatrist.

“Most of the kids we deal with [at the Resistance Network] are street kids, or will be,” Hay told PGN. “They can’t afford a psychiatrist. So advice about building a file on one’s gayness is to some extent a class thing.”

Killinger ultimately recommended to PGN readers eligible for the draft that “it cannot be stressed enough that young men ought to begin thinking about these issues as soon as possible. It can help tremendously to talk to a counselor about selective service options,” and he listed several organizations and resources that could provide assistance and information.

While we now know that a military draft was not instituted after the Vietnam War, the fear of it in the 1980s was palpable among the gay community. As PGN always did and continues to do, it provided insight, information, and ways to help the community through this uncertain time.