In honor of Black History Month, the National AIDS Memorial Project and the AIDS Memorial Quilt is displaying 56 panels commemorating Black lives lost to HIV/AIDS. The virtual exhibit reminds viewers that people of color were hit extremely hard by the virus; it was a leading cause of death for Black men aged 25 to 44 in the early 1990s, and it affected people regardless of age or gender.

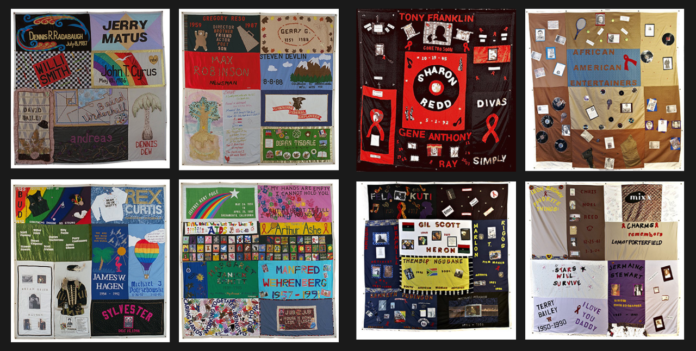

The panels of those memorialized by their parents, siblings, colleagues, classmates, coworkers, friends, and advocates show a cross-section of lives taken too soon. Moreover, the exhibit comes at a very poignant time when the world is dealing with another global health crisis.

“Look no further than the current pandemic as an example,” said Keisha Gabbidon-Howell, Prevention Education Services Supervisor with Philadelphia’s healthcare organization Bebashi. “Like HIV, marginalized communities have taken the brunt of COVID-19’s impact, and still have less access to the vaccination.”

Gabbidon-Howell, like many prevention experts, AIDS-related healthcare providers, and others in the medical field, is still acutely aware of the continuing HIV/AIDS health disparity taking the toll on Black lives. As recently as 2018 there were 38,000 new cases of the virus reported in the United States. A staggering 42% of that number were members of the Black community, with half that number of patients living in the South.

“It is important that HIV awareness remain relevant because we have not yet ended the epidemic,” Gabbidon-Howell said. “While, fortunately, there have been several breakthroughs and more resources exist today for people living with HIV, access remains a crucial barrier for many marginalized communities. Making people aware of the tools available i.e., education, testing, PrEP/PEP, is a sure way to prevent new HIV cases, or at the minimum keep them stable.”

The curated section of the AIDS Memorial quilt includes panels that tell the stories of those “countless men, women and children who have died and the impact AIDS has had on the Black community.” Several of the displays in the exhibit are the result of the Call My Name program, which was created in 2013 to draw attention to the impact of HIV/AIDS in the Black community by fostering the creation of new quilt panels by Black Americans to honor those they have lost.

People memorialized in the panels include Max Robinson, a news journalist who was the first Black person to co-anchor a national broadcast at ABC in the late 1970’s; Willi Smith, a fashion designer who pioneered streetwear; Stephanie Waller and Conrad Waller, a mother and son who died one year apart; Fabianne Curtis, a 19-year old college student attending Babson College; and Chakena “CC” Conway, a poet, health motivator, advocate, activist and youth representative who co-founded the Positive Women’s Network.

“This virtual exhibition shares stories of hope, healing and remembrance to honor Black lives lost to AIDS,” said Delaware Valley native John Cunningham, who serves as Executive Director of the National AIDS Memorial. “Our hope is that it helps raise greater awareness about the ongoing struggle with HIV and the impact systemic barriers have to positive health outcomes, particularly among the Black community.”

“Today, Black Americans face the highest impact of HIV/AIDS compared to all other races and ethnicities,” said Raniyah Copeland, President and CEO of the Black AIDS Institute. “This highlights the need to center Black and LGBTQ people in the fight to end the epidemic. By sharing these powerful stories from the Quilt, we can continue to advocate for Black people living with HIV, defy stigma, and create awareness around prevention and treatment options available today that can end HIV in Black communities over the next decade.”