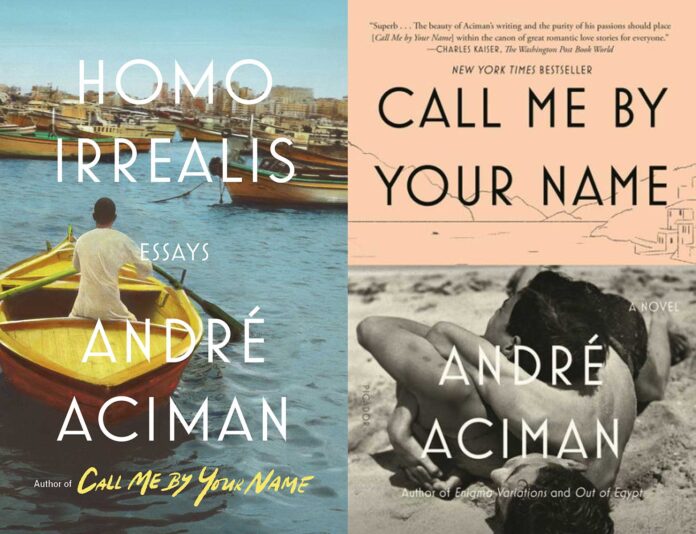

Author André Aciman, who penned “Call Me by Your Name” and its sequel, “Find Me,” has a new essay collection, “Homo Irrealis.” The title comes from the irrealis mood in linguistics, a liminal space where “the might-have-been hasn’t happened,” or “might still happen.” Aciman equates this to “awaiting nostalgia.” When he and his family are about to leave Alexandria for France, he describes being homesick for Egypt — even though he has not left his native country yet.

Such wistful emotions inform his essays in this volume as well as his novels. Each chapter addresses some “might-have-been life.” Aciman often searches for the site of a favorite film or a book to “slip into that world,” or “borrow the lives of its characters” so he can bask in a fictional space that speaks to him.

For example, in 1984, after Aciman saw “The Apartment” at a cinema in the Upper West Side of New York, he roamed the streets of city for the apartment in the film, which was said to be on West 67th Street. He later learned that the building was torn down the previous year. Moreover, Aciman discovers, the building that inspired “The Apartment” was actually on West 69th Street. However, he does not seem to mind. Aciman sees the film again and repeats the same pilgrimage the next day to recapture the feeling “The Apartment” gave him. “This film was about me,” he writes, to explain his obsessive connection to it.

The same association is apparent in the author’s three essays about Eric Rohmer’s films, “My Night at Maud’s,” “Claire’s Knee,” and “Chloe in the Afternoon.” Aciman’s appreciation of the French New Wave filmmaker stems from his identification with the male protagonists, whose efforts to resist the titular woman in each film often drives the character to declare his love for another woman. Rohmer’s work entrances Aciman because each film depicts a “what might-have-been” romantic situation. And the author peppers his discussions with his personal “what might-have-been” romances.

“Homo Irrealis” does have a confessional tone. In his essay, “In Freud’s Shadow, Part 2,” Aciman describes an encounter on a crowded bus in Italy in which a young man was pushing himself/being pushed against the author’s body. Leaning into the other passenger, Aciman wants the sexually-charged moment to last, but it ends quickly. The young man is never seen again; Aciman tried to find the stranger on the same route in the subsequent days. But the powerful hold that episode had prompts the author to take that same bus ride when he is in Rome to recapture that evening and relive that impressionable experience. The what “might-have-been” resonates.

This anecdote illustrates another vivid point Aciman makes throughout “Homo Irrealis,” that his experiences dictate who he might have become. There is a sense of possibility in this irrealis mood he describes. He could have had a tryst with that young man on the bus. He could have stayed in Alexandria and not moved to France or New York. His life could have always turned out completely differently. But such unrealized opportunity is what guides Aciman, who has “a nostalgia for what never happened.”

This is what is so appealing about Aciman’s writing. He may get too inside his own head, but he gets deeply inside the heads of his characters in his novels. “Call Me by Your Name” is steeped in the mindset that Elio has for Oliver. “Eight White Nights” (arguably his best book) chronicles a series of encounters between a young man and a woman who are always on the brink of consummation. The constant thinking and processing of “the might-have-been” or “might still happen,” creates tension and suspense.

However, it can also be exhausting. “Homo Irrealis” is, at times, quite dense, but it is balanced by chatty entries on topics ranging from paintings by John Sloan and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot; Beethoven’s music, and James Joyce’s “The Dead;” Lawrence Durrell and the gay poet Cavafy; a visit to St. Petersburg; and an analysis of the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa. (Some of the chapters have been previously published). One of the droller essays is his short doodle about the word “almost,” which Aciman says is inconclusive. “It is not a yes or a no; it is almost always a maybe.”

Aciman also includes an entry about one of his favorite subjects, Marcel Proust. (He edited a book on the gay author and teaches classes on his work at the Graduate Center at CUNY). He justly marvels at the Frenchman’s elaborate sentences, several of which appear in “Homo Irrealis,” and the way time is portrayed in “In Search of Lost Time.” There is always a lack of present tense, Aciman observes about Proust’s writing.

And this may be the root of all of Aciman’s yearnings and longings. His collection is an amalgam of desires, fantasies, and reality as seen through the lenses of art and life. By sharing them in “Homo Irrealis,” Aciman allows readers to absorb these thoughts and filter them through their own lives and experiences.