Research shows that eating disorders, thoughts of self-harm and suicide attempts are higher among LGBTQ+-identified individuals.

“The community itself endures certain types of stressors that heterosexual and cisgender individuals typically don’t,” said Roni Levy, team leader at the Renfrew Center of Massachusetts. At the Renfrew Center’s annual conference, which took place virtually from mid-November to mid-December, several presentations and discussions addressed eating disorders within LGBTQ communities.

As part of the conference, Levy presented a webinar on eating disorders in the LGBTQ community, where she talked about influences, treatment and prevention. Levy also co-led a discussion with Cindy Gretzula, assistant vice president of clinical support services and director of nursing at the Renfrew Center Florida, called Facilitating Dialogues on Privilege, Power and Pride: Intersectionality within the LGBTQIA+ Community. The Renfrew Center is specifically geared toward treating patients with eating disorders and has locations around the country, including Philadelphia.

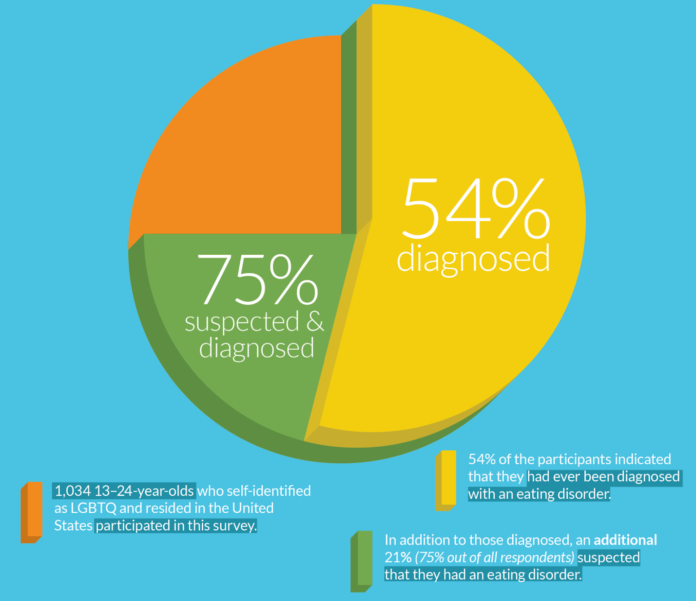

A 2018 report by The Trevor Project, National Eating Disorders Association and Reasons Eating Disorder Center shows that young cisgender female LGBTQ people had higher rates of eating disorder diagnoses than any other gender identity in the survey. Of the female-identifying youth in their survey, 54% reported having been diagnosed with an eating disorder, the most prevalent of which was bulimia. Forty percent of gender noncomforming and genderqueer youth in the survey reported being diagnosed with an eating disorder, and 39% of trans males reported the same. Out of youth who identify as another gender, 60% reported an eating disorder diagnosis.

In terms of sexual orientation, LGBTQ youth who identify as straight but not cisgender reported higher rates of eating disorder diagnoses than those of other sexual orientations, clocking in at 71%. Out of the bisexual LGBTQ young survey participants, 51% reported being diagnosed with an eating disorder, and 45% of gay or lesbian LGBTQ youth reported having an eating disorder diagnosis. Thirty-five percent of LGBTQ youth who conform to other identities, like asexual or pansexual, reported the same. The report found that eating disorders throughout sexual orientations and gender identities manifest most commonly as “fasting, skipping meals and eating very little food.”

According to NationalEatingDisorders.org, potential risk factors that can lead to the development of eating disorders in LGBTQ youth include fear or experience of rejection by friends and loved ones, internalized harmful messages about one’s sexual orientation or gender identity, violent experiences and/or post-traumatic stress disorder, encountering discrimination or bullying related to one’s sexuality or gender identity, experiences of gender dysphoria and “inability to meet body image ideals within some LGBTQ+ cultural contexts.”

“Someone who identifies as nonbinary, they often experience a desire to present as very androgynous, so obviously the control aspect over their body helps them to achieve that,” Levy said. “Even in the lesbian and gay and bisexual communities, I think, related to clothing and gender expression — for example, I hear my patients talk about ‘butch lesbian,’ ‘soft femme,’ things like that. There are certain expectations that are also intertwined with the body.”

Levy also explained that people with intersectional identities tend to be at higher risk of struggling with an eating disorder. NationalEatingDisorders.org reports that Black teenagers are 50% more likely than white teens to display bulimic behavior, Hispanic adolescents are substantially more likely to suffer from bulimia than their non-Hispanic peers and trends indicate higher rates of binge eating disorder in all minority groups. The report also found that people of color who worry about their own diet and weight were much less likely to be asked by a doctor about eating disorder symptoms, even though many different racial groups experience similar rates of eating disorder symptoms.

“You add on things like racial discrimination, age discrimination, ableism, things that really play a significant role in how they’re treated by society at large and therefore impacting their sense of self and their relation with others,” Levy added. “We find within eating disorder treatment that any stressors that are related to relationships and connection really take a toll on people just because connection is so vital for all of us.”

Multiple paths exist in terms of lessening and preventing eating disorders, including better training for medical professionals to properly identify the symptoms of an eating disorder “because they may present a little bit differently for someone in the LGBTQIA+ community,” Levy said. “Over the years what I’ve noticed is — what used to be called ‘diet mentality’ is functioning under this mask of the wellness approach. What’s happening is that these eating disorders are going undetected because it’s become the norm to essentially fixate and focus in on one’s body and the way in which they eat.”

Although eating disorders can lead to medical complications, the Renfrew Center team refers to them as emotional disorders, Levy said. “They’re definitely under the umbrella of mental illness, it’s just dependent on the angle you’re looking at it from.”

Education for all parties is paramount, Levy added.

“Even with my patients who may feel reluctant to admit that they are struggling with an eating disorder — it’s kind of this cost/benefit analysis,” she said. “At what cost are you engaging in these behaviors, and what is the impact on your quality of life? Oftentimes these individuals are sitting in a pool of emotional turmoil. I think that it goes unrecognized because it’s such a norm within our community to feel guilty for eating something, for having to ‘work it off.’”

Just as psychological trauma can manifest in an eating disorder, it can also manifest in other types of self-harm and thoughts of suicide, which also tend to occur at higher rates among LGBTQ individuals.

“Transgender people tend to show really considerable risk compared to LGBTQ people in general,” said Wren Gould, licensed clinical social worker at the Einstein Healthcare Network. They focus on providing their clients with LGBTQ-competent services.

According to the Trevor Project, a national study indicates that 40% of transgender adults reported having attempted suicide. Of those people, 92% reported having a history of attempted suicide before the age of 25.

Prime causes of suicide attempts and thoughts of self-harm among the people sampled include experiences of familial rejection, Gould said. People who are also at risk of self-harm include those who encounter violence related to their gender or sexual orientation, and gay men in relationships. “There also are significantly higher rates of intimate partner violence amongst communities of gay men,” they added.

In terms of seeking help with depression and thoughts of self-harm, Gould presented several options. It can be helpful to reach out to someone, especially with the availability of social media, texting and other ways of digitally connecting, be it with a close friend or acquaintance.

They also suggested using the internet to connect with folks and find resources, especially for members of the trans community. Philadelphia LGBTQ organizations have a number of trans-centric groups and resources, like the weekly meeting TransWay, which Kendall Stephens and Elizabeth Coffey Williams facilitate digitally. Mazzoni Center also publishes an annual Trans Resource Guide, which includes information about mental health therapists and psychiatrists.

“That’s definitely a way that people seek support and find a sense of relief — being able to find other people that have a similar experience or just being able to talk about whatever is actually causing them that emotional pain,” Gould said. Conversely, talking to someone about anything else, like a favorite TV show or book, can be “distracting from the emotional pain you may otherwise be sitting with,” Gould added.

Gould emphasized that it’s OK to seek out emergency services if need be, like calling 911, although they acknowledged the reluctance that some LGBTQ people feel toward contacting the police. Taking oneself to a psychiatric emergency room, perhaps with a friend, is another option that Gould pointed out.

“Many hospitals in the Philadelphia area do have what are called crisis response centers,” Gould said. In the Philadelphia area, such crisis centers exist at Einstein, Hall-Mercer Community Mental Health Center, Mercy Philadelphia Hospital, Temple University Hospital and Belmont Behavioral Health Center.

“It’s really OK to contact emergency services in a number of different ways if you’re feeling like you’re really worried about your safety,” they added.