If you live in Philadelphia and have ever entertained a tourist, chances are you’ve repeated the three or four hallmarks you’ve heard about Philadelphia and France: the Ben Franklin Parkway was modeled on the Champs Elysees in Paris; we had a world-famous French restaurant Le Bec Fen; we’ve got a lot of impressionist artworks. But the roots of Philadelphia’s intersection with France go much deeper than art, architecture, or appetizers.

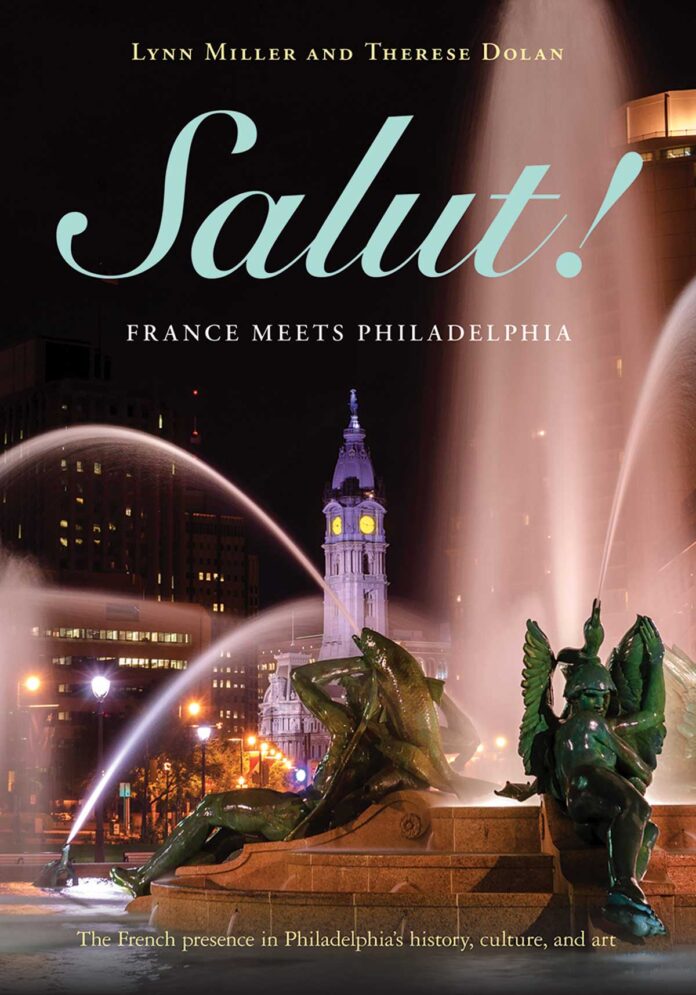

In the book “Salut! France meets Philadelphia” (Temple University Press) authors Lynn Miller and Therese Dolan chronicle 300-years of intertwined politicians, artists, architects, chefs, entrepreneurs, and city planners between the city of brother love and America’s first ally.

Starting just before the arrival of William Penn, “Salut!” opens with the reason Philadelphia was founded in the first place: as a land of religious tolerance. As many emigrants (including the French) fled intolerant Europe and moved to the British colonies of North America, they found that religion was less problematic than nationality. France and Britain were locked in an intense struggle to stake their claim in the new world. But it was that very struggle that set Philadelphia on its path to be a city of English origins but strong French influence. That combination, present all over the city throughout its history, is the heart of the book.

Along with helping the colonies defeat the British Empire, the French contributed much to the young United States in the way of aesthetic philosophy and the law as well. America’s founders looked to Montesquieu’s L’Espirit des lois (The spirit of the laws) for help in governance and politics. In the 1750s, the College of Philadelphia (now known as the University of Pennsylvania) had it on their reading list. When we talk today, amidst the turmoil and chaos brought by Donald Trump, about the America that our founders idealized, it is Montesquieu’s vision of freedom from oppression that they envisioned.

One of Philadelphia’s most important inhabitants, Benjamin Franklin, was highly responsible for bringing French culture to the forefront. But he also courted French assistance in the war effort. In that sense, Philadelphia served as the spark that truly lit the flame of revolution, and France helped provide much of the kindling.

“Salut!” goes far beyond Franklin, however, and highlights some of the lesser known figures that brought French influence to the city. From 1790 to 1800, when Philadelphia was the capital of the country, more than one in ten residents were French. The influx of French dentists, whose techniques and training were more advanced than the colonies, helped the oral hygiene of Philadelphians even as Thomas Jefferson helped popularize ice cream, another French import.

Philadelphia’s art history and art present owe much to France, and the book spends an understandable amount of time detailing French artists whose works populate the city (Rodin, Renoir, Cezanne) and the city’s native artists who went to France to find better prospects (Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassat, Henry Ossawa Tanner).

Paul Cret, whose name is likely not known to most Philadelphians but whose work and influence is felt throughout the city, is also given ample space in the book. Cret, a French-born architect, designed the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, the Rodin Museum, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, among other buildings around the country, and he taught at the University of Pennsylvania.

The book points out that almost every area of Philadelphia, not just obvious sections like Rittenhouse Square and the Art Museum area, has French influence. Point Breeze, for example, was home to Napoleon’s brother Joseph Bonaparte’s estate — one of the most lavish houses in the Delaware Valley — as well as the home to many of French ancestry including the Bouvier family, whose patriarch Michel created furniture for Stephen Girard’s home on Water St. Girard, understandably, also receives much attention in the book for his contributions to the city. It’s nice for a reader to learn more about him than just the avenue, college, and subway stop named after him.

“Salut!” provides readers with a wonderful glimpse into the French flair that Philadelphia has proudly brandished for centuries. As a coffee table book or a serious academic study, it’s accessible to a wide variety of readers. And for anyone who has wanted to take pride in Philadelphia’s French roots, it’s a must-read.

For those interested in learning more about the book, the authors will participate in a Zoom event “A Salute to Salut!” on December 9.