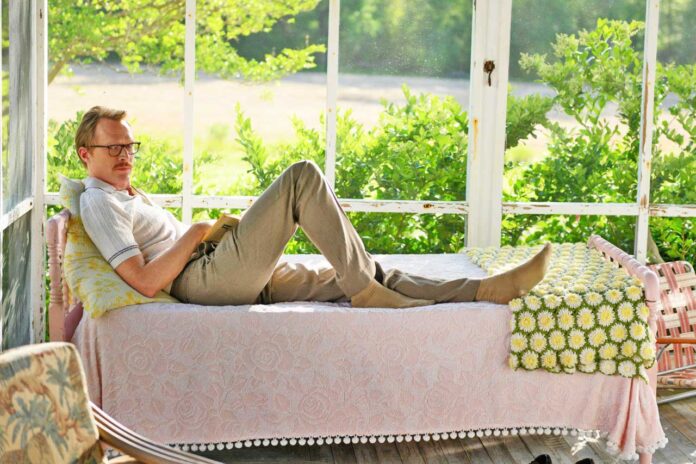

Out gay writer/director Alan Ball’s engaging drama “Uncle Frank,” available on Prime Video November 25, is an original story but feels like an adaptation of a Southern novel. The film is narrated by Beth (Sophia Lillis), a teenager who is related to the title character Frank (Paul Bettany).

It’s 1969, and Frank and Beth have a pivotal conversation in the Creeksville, SC home of Frank’s father, Daddy Mac (Stephen Root). Frank, who is the black sheep of the family, tells his niece to, “Be the person you decide to be, and not the person everyone wants you to be.” The talk motivates Beth, who four years later, becomes a freshman at New York University, where Frank teaches. And it is in New York where Beth learns not only that Frank is gay, but that has a lover, Walid “Wally” (Peter Macdissi, Ball’s real-life partner). When Daddy Mac dies, Frank and Beth take a road trip to the funeral, prompting Frank to perhaps come out to his family.

Bettany gives a fantastic performance as Frank, shifting from the inspiring uncle to a man who becomes anxious and scared as he returns to his hometown and grapples with some serious emotional demons. In a recent phone interview, the actor spoke with Philadelphia Gay News about playing “Uncle Frank.”

Did you have an “Uncle Frank” in your life? Not necessarily a gay or closeted family member but someone who inspired you to become who you are?

My uncle Theo and auntie Jill. They were married and surrogate parents for me. He gave me a really great non-toxic model of masculinity. And there was a woman called Shosh, who was a surrogate mother. They all gave me glimpses of a wider world.

What can you say about this duality of Frank’s character?

To outward appearances, he is nice and polite, and seems to be living his best life, but he lies to protect his family and himself. I think that schism between who he is in South Carolina and who he is in New York embodies this issue. It’s a movie for anyone who has struggled to live authentically because of pressures outside themselves — whether religious, or societal, or familial. I hope “Uncle Frank” speaks to people. Frank compromises himself because of the shame he feels.

Let’s talk about his self-hatred. As he gets closer to home, his emotional state becomes more fragile and exposed.

All that niceness and carefully curated look of the scholarly professor — he has less of an accent in New York. Suddenly, as he gets closer to home and his past, the cork becomes to loosen in this tight bottle. He tries to tamp it down, but these two worlds crash together — especially when his father wreaks havoc from beyond the grave. Luckily, Frank has the love of a great partner to hold him together and help him survive this terrible crisis. Frank is behaving badly, but you get to really understand who he is beyond the witty, erudite mentor. You see the dirt and love him more.

Yes! He becomes more sympathetic as a result. How did you approach Frank? He isn’t a stereotypical gay character, but a gay man who passes.

I absolutely didn’t consider some gay specificity, whatever that might be. I wanted Frank to be a man struggling with himself and who he was and is. My father wasn’t camp in any way, and he came out at 63. He was passing. He was a closeted gay man all his life and had a 20-year relationship with a man called Andy who was undoubtedly the love of his life. When Andy died, my father went back into the closet and denied the relationship. My father was a Catholic and my brother died early, and [Dad] felt he wasn’t going to get into Heaven to see his son. He was full of shame, and that had consequences for me, my family, and his wife. He had curated stories and passed them off as family history, but he had a secret history. That was a tragedy for me and him. When he came out, it was a release for him and everyone, and it was not in any way a surprise.

I also admire how you recalibrate Frank’s interactions. Frank reads a room well as in his exchange with Beth’s boyfriend, Bruce. But I particularly love Frank’s body language when he enters and sits, like a little boy in trouble, when he first sees his mother [Margo Martindale] during a key scene. How did you develop this aspect of his character?

I really didn’t consider his body language. What is interesting is that I don’t smoke like Frank does, but my father smoked like that. My father was hyper aware of the room. The scene you reference with Frank’s mother, happened by mistake. It was written that [Margo] was upstairs and called Frank, and I walked to the bottom of the stairs. Margo said, “Why don’t I sit in Daddy Mac’s chair?” I walked in and I was terrified. I think it’s a really moving moment.

It is! Frank really does not want to be part of his family. How do you think his life would be different if his father had been accepting of him?

Oh, my God, in a myriad of different ways. The stuff of growing up and learning to accept yourself and be right with yourself — Frank has not done that in a real way because he is hiding.

I have a friend in his 50s who is terrified of coming out to his family. This is a period film, but it is still pertinent now.

“Uncle Frank” is a road trip film. What do you like or dislike about this genre?

I love them. You have a very clear objective — to get from A to B, and you have the ability to meander both physically and emotionally. I love road trips because you really get to know people.