For better or worse, humans have a remarkable tendency to use myth, fables, and legends to help them better understand the world around them. The notion of such storytelling likely predates even proper language itself, going into the dimmest reaches of history as an oral tradition of passing on communal wisdom in the soot covered walls of our oldest ancestors’ caves.

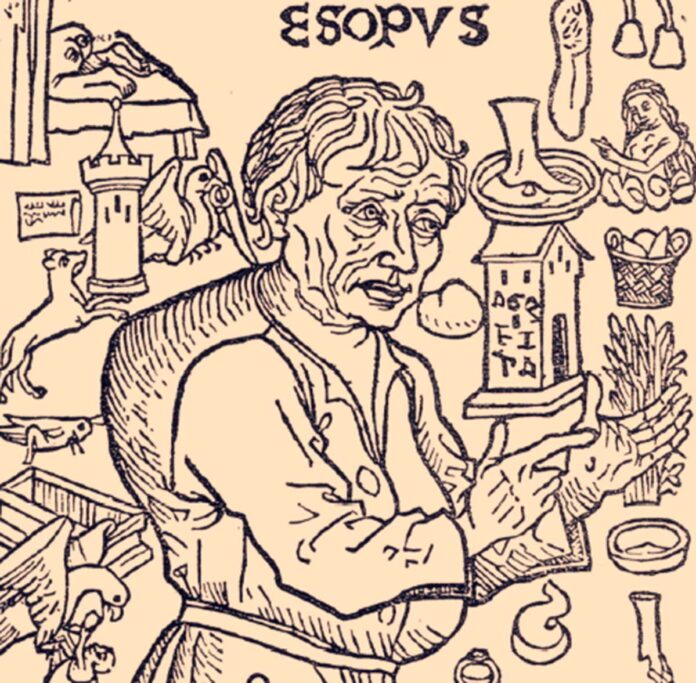

Of the many historical storytellers, Aesop is one of the first we have a name for. He was supposedly a slave and a storyteller, living in Ancient Greece some 500 or so years before Christianity, and his stories would begin to dominate culture. Aesop may have been themselves a myth created by other storytellers, and it’s plenty likely that the majority of their stories come from others.

Sometimes, with a good story, it’s not so much who told it originally, but what the tale conveys that matters.

In Aesop’s Fables 517, dating from Ancient Greece, circa the 6th century BCE, a curious story of Prometheus is relayed.

Prometheus, for those who may not know, was the Titan god of fire. Once he stole fire from the Gods and gave it to humanity, leading to him being chained to a rock, where an eagle would consume his liver daily, only for it to grow back overnight. Many viewed that fire as more to do with the flame of inspiration, rather than any literal embers.

That tale, however, is not what I wanted to share. You see, Prometheus was credited not only for his theft of fire, but also with the creation of humankind, sculpting us out of clay before bestowing us with the fire that, presumably, brought us to life.

Aesop embellished on this story, explaining in Fable 517 on the creation of lesbians and gay men that may, in fact, hold even more relevance for transgender people. Allow me to quote from Laura Gibbs’ translation of the Fable, from 2002.

“All day long, Prometheus had been separately shaping those natural members which Shame conceals beneath our clothes, and when he was about to apply these private parts to the appropriate bodies, Bacchus unexpectedly invited him to dinner. Prometheus came home late, unsteady on his feet and with a good deal of heavenly nectar flowing through his veins. With his wits half asleep in a drunken haze he stuck the female genitalia on male bodies and male members on the ladies.”

I bring this story up because humans are truly formed by a common clay of sorts, a set of genetic sequences that lead us throughout our earliest development. There are, indeed, those who would try to convince you that such development is some infallible act, a product of a all-powerful God or a set of long-perfected scientific ideals.

Admittedly, most days that’s true: a pair of cells will meet, divide, and eventually form a viable human being.

Yet we know that isn’t always the case. Humans carry variations from their parents genetic material, and other changes and mutations can form as one develops.

Consider, for example, handedness. Roughly 10% of the humans on this planet are left handed. You know, just about the same number are potentially gay, lesbian, or bisexual. Likewise, 1-2% of humans have red hair, roughly equal to how many people may be transgender.

I want to clarify, too, that when I speak of such things, I want to make it clear that I am not trying to conflate intersex people with transgender ones. Perhaps at some point, we might find stronger ties between both transgender people and intersex people — but for now, let’s tread carefully and avoid erasing anyone.

Last week, I was made aware of an interesting study from the National Center for Biotechnology Information by William J,. Anderson, et al. in it, researchers noted the formation of prostate tissue within seven of eight bodies of trans masculine people using testosterone that they studied.

In the human body, when it is forming, the genitals are initially a single structure. Gonads and other parts are undifferentiated. Within week 7 and 12, the body with usually go one of two ways, Forming into a penis, scrotum, and testicles, or into a clitoris, womb, vagina, etc.

At the same time, we’ve seen stories showing that trans women’ hypothalamus may be more in line with that of their non-trans siblings, rather than that of men. There’s a lot more story to be done.

Going beyond the studies, I cannot help but think of the hundreds of stories I have heard — as well as my own experiences — when a transperson starts hormone replacement therapy. The descriptions are poetic, of cloudy skies clearing and such. For me, it was like an annoying car alarm finally being shut off after blaring for years.

Hormone replacement therapy is our clay: it affects the trans body in ways big and small. As the trans community has begun to share information among ourselves, we’ve learned so much more about what hormones do to us than we had been told: everything from changes in food tastes to monthly cycles happen to us.

There are those who would tell you that transgender people’s genders are innately the same as the one they were assigned at birth. How is this different from that omnipotent God, creating every human with a watchmaker’s precision?

Yet transgender people are not this. We are Prometheus’ clay, both potentially formed differently from others, and malleable by us as we live our lives. We are not eternally tied to the destiny we were assigned by a doctor when we breathed our first air.

Gwen Smith already liked Prometheus when she only know the fire story. You can find her at www.gwensmith.com