When Spectrum, the undergraduate LGBTQ student group at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, launched in 1983, it became a resource not just for those on campus but for queer people living in that part of the South. Over time, people from hundreds of miles away rang its office seeking support and referrals for services.

If nobody picked up the phone, callers left messages on an answering machine. Such devices are largely relics today, but somehow the one used by Spectrum survived with its original tape. A librarian and faculty member who had advised the group for years had stored it in her garage.

“When I plugged it into the wall, it was so heartwarming and heartbreaking to listen to it. All these people were saying, “I am so glad you are here,’” recalled Joshua Burford, who earned undergraduate and master’s degrees from the university.

Burford, 45, who is queer and grew up in Anniston, Alabama, first listened to the recorded messages in 2008 while assembling the Miller-Stephens GLBTQ UA Student Organization Collection housed at the University of Alabama Libraries Special Collections. About a decade prior he had met with the student group’s first faculty adviser, who agreed to turn over the archival material stored in his garage.

“I built this tiny collection out of, I think, five boxes,” recalled Burford. “But man those five boxes set me on a completely different course in my life.”

In 2013, he had taken a job as an assistant director for Sexual & Gender Diversity at UNC-Charlotte in order to create the city’s first LGBTQ archive housed at the campus’ J. Murrey Atkins Library. Known as the King-Henry-Brockington LGBTQ+ Archive, one of its oldest contents is a stash of photos from 1940 detailing a queer bar night held at the Barringer Hotel’s Hornet’s Nest Lounge in Charlotte.

A lesbian who worked as a bookkeeper at the hotel started inviting her queer friends to the bar on Tuesday nights after realizing it was largely bereft of patrons on those evenings, recalled Burford.

“So it became this underground guerrilla gay bar,” he said.

In 2018, Burford moved to Birmingham, Alabama to work on launching the Invisible Histories Project with a fellow academic, Maigen Sullivan. The project sought to preserve queer Southern history, particularly in the states of Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. Burford and Sullivan first met in the mid-2000s on the Tuscaloosa campus of the University of Alabama, where Sullivan also received her undergraduate and master’s degrees.

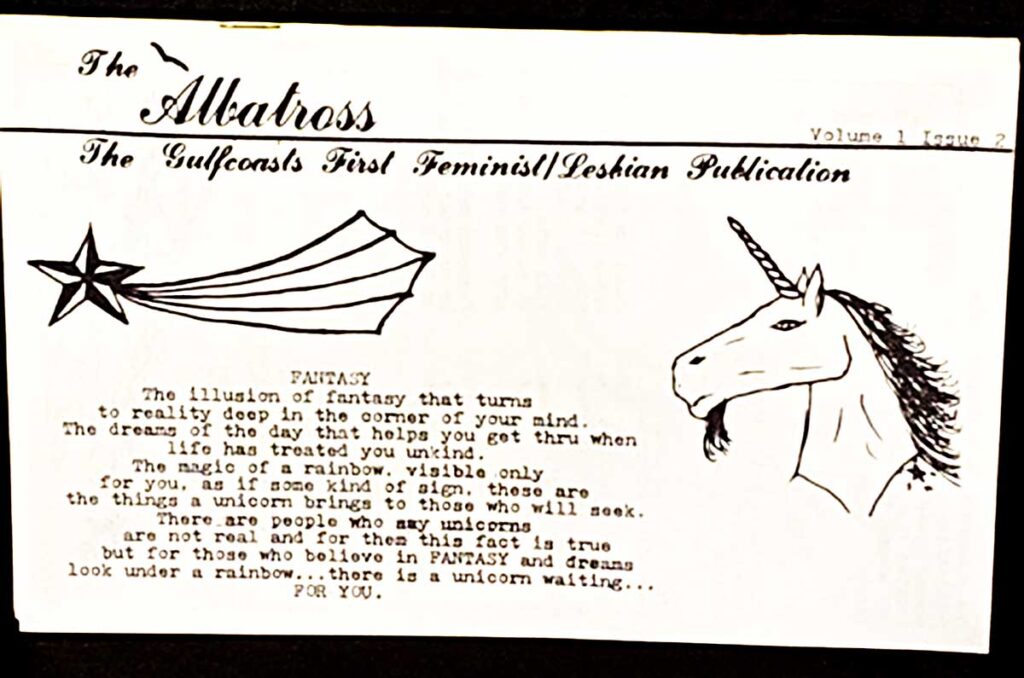

Rather than the story of the queer South being one of LGBTQ people fleeing for the coasts to find acceptance and community, they are unearthing how LGBTQ Southerners thrived in their hometowns. For instance, an LGBTQ community center opened in Birmingham in 1980, noted Burford, while there were various queer publications across the region in the 1970s.

“We can’t see us because we have been fully ignored this entire time. The South, especially the queer South, exists as a cautionary tale,” said Burford. “And as long as we are a cautionary tale, we can never be anything else. We are trying to fix it.”

Nonprofit formed

In 2016, Burford and Sullivan formed a nonprofit to begin raising awareness about, and money for, the archival project. A grant last year from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation afforded them both the ability to work full-time on the project. Burford is its director of outreach and lead archivist; Sullivan is its director of research and development.

“We both were really disappointed in the stories and narratives about being queer in the South we had been told for like, forever, or the lack of stories and access we had had,” said Sullivan, 37, who is queer and grew up near Sand Mountain in the Appalachian part of Alabama. “We knew all these amazing people, and not just currently living but had heard stories of other people. How can we let other people know what we know?”

A similar project is underway at the Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive housed at the special collections department of the University of Memphis campus library. A group of eight interested preservationists formed the LGBTQ Community of Researchers in 2018 and received a $2,500 seed grant from Tennessee’s public research university to launch the archive.

Last spring, the group took possession of the LGBTQ+ community center OUT Memphis’s historical records.

“They had all this stuff in closets. By us taking it and putting it in the library, hopefully it will make it more accessible to the community,” said Robert “Robby” Byrd, 40, a gay man who grew up in the rural Mississippi town of Amory and is now an assistant professor of journalism at the university.

The Mid-South archive is focused on preserving queer history in Arkansas, Mississippi, and parts of Tennessee and Missouri.

“It was important to start this because there was no other formal repository of queer history in the area that existed,” explained Cookie Woolner, 46, a queer femme who has been a history professor at the university since 2016. “There wasn’t a centralized place, archive, or organization focused on compiling local queer history.”

Byrd added that they are working to ensure it isn’t seen as an “ivory tower” collection meant solely for academic research and use.

“We want it to be a community archive so people feel comfortable using it and feel comfortable contributing to it,” he said.

Brigitte Billeaudeaux, 37, a queer questioning cisgender female, has worked as a librarian and archivist for special collections at the Memphis campus and is helping to organize the queer archive. It aims to collect everything from people’s paper records to the queer ephemera they have saved.

“We can also give people the option to donate just images of their artifacts or allow us to image it so they can keep their possessions,” she said.

Gay Memphis native Vincent C. Astor, 66, who helped found the city’s LGBT community center and writes about Southern queer history for various local publications, donated items he had collected over the years to the archive. He has a number of archival collections housed at local institutions, including the city’s public library, which only collects two-dimensional historical records, and the local history museum, where he donated ephemera from the city’s Pride event, like T-shirts and souvenirs.

“I have always been interested in history and historic preservation,” said Astor, known as the official historian of Memphis’ gay and lesbian community.

He gave his collection of old gay newspapers to his alma mater Rhodes College, which was known as Southwestern at Memphis when he earned degrees in German and theater there in 1975.

“When I heard about the archive at U of M, I gave them a big boatload of my stuff, the physical stuff. I had a lot of mementos from the Emerald Theater Company,” said Astor, referring to the local gay theater troupe with which he had performed, including twice as the flamboyant Emory in productions of the play “Boys in the Band.”

He hopes the archival material will shed some light for today’s young people and future generations about what it was like to be a gay man in the South.

“Young people’s frame of reference is so far removed, even from AIDS, that they have to be taught a little more intensely,” said Astor. “I am a museum person, I know these things just slumber until they are needed. That doesn’t bother me at all. I just like the fact that they are there if someone like me comes along in 25 years and wants to know what it was like.”

Film, video collections

One of the archive’s prized possessions is video from 51 years ago of the first Miss Memphis Revue, a drag show held on Halloween, as it was the only day men could legally dress in women’s clothing. A crowdfunding campaign netted $2,000 to digitize the 16-millimeter film.

There is additional film of the annual event they hope to also digitize at some point.

“There is quite a bit of film. We have no idea what’s on it,” said Billeaudeaux. “It was donated to OUT Memphis at some point. It is unclear if it was given directly from the person responsible for the film or given to someone else and then passed on.”

When she also found a letter in the donated materials from Bill Kendall, the founder of the drag event, that helped to contextualize the videos, “My hairs were standing up. I had goosebumps,” said Billeaudeaux.

Via its Instagram and Twitter accounts at 901lgbtqarchive, the archive routinely posts images of its holdings in order to help raise awareness of the collection. It would like to add more personal narratives from people in the community, especially those who are Black or Latinx.

“I think that is necessary to help tell the story,” said Billeaudeaux. “I would like to expand our narrative beyond one side of what we have seen, mostly European American history.”

A conduit for queer history

Sullivan and Burford’s Invisible Histories Project is unusual in that it is not working to build its own archival collection about Southern LGBTQ history. Rather, they aim to connect LGBTQ people with established institutions, whether a local or university library’s historical collections, a collecting museum, or a historical society, where they can donate the items they have preserved over the years or record their oral stories about their lived experience in the South.

“We are an intermediary between queer and trans people and organizations and libraries and universities and museums,” said Sullivan. “We are a conduit. We research and locate potential collections.”

Their aim is to ensure the archives are accessible to the local queer community, noted Burford.

“I think one of the central tenets of our work is we want the materials to stay local. As local as we can keep it and as close to the communities that produce it,” said Burford. “Now, at some point in the future, if there is a drive or desire for a History Center for the Queer South, that is certainly something we wouldn’t say no to.”

In the meantime, Burford feels an urgency to the work they are doing to preserve not only people’s memories but also memorabilia.

“I know it sounds a little hyperbolic, but I wake up at night thinking about how much we have lost,” he said. “What went into the trash intentionally and unintentionally?”

They have utilized social media to their advantage in seeking out people and materials. In some cases they tag individuals online they are interested in talking to, and in others people reach out to them.

“When we go to meet someone for collecting, we ask them for 10 to 15 people we should talk to,” said Sullivan. “It is old school, grassroots queer Southern networking.”

Such was the case when Janelle Sweeney, a straight woman who lives in Birmingham, contacted the project out of the blue about a guide to gay bars she had discovered at an estate sale. Sweeney resells vintage and kitschy items she finds via her Instagram and Facebook pages under her business name of Janelle’s Attic Gold. Her former boyfriend, who is bisexual, happened upon a cache of men’s fitness magazines at an estate sale they had stopped at and came running over to her excitedly to ask if she wanted to buy them.

“I said, ‘Fuck yeah, grab it all!’ It was my beefcake jackpot; it was amazing,” recalled Sweeney, who believes she paid around $10 for the four boxes worth of old publications.

Thinking she could resell the muscle magazines, Sweeney was sorting through them when she was amazed to discover a second edition of the 1964 International Guild Guide to various gay bars from around the globe.

“I was fascinated. This one I had was international and had gay bars from just about everywhere all over the world, from the U.S. to Greece,” said Sweeney.

She ended up donating the guide to the archival project at the suggestion of a friend who is part of the local kink scene and had seen her social media post about it.

“I never knew it existed,” said Sweeney, who was impressed by their passion to preserve LGBTQ history. “Just the drive they had about it, especially for saving ephemera. It is a beautiful part of history that was never meant to have lasted.”

Sullivan and Burford are working on their first queer history exhibits based on the materials they have collected, one of which will be a small virtual exhibit they hope to unveil online later this year. In the spring they aim to open a larger exhibit on Birmingham’s LGBTQ history at a local art gallery in the city’s downtown, while the third isn’t ready to be revealed at this time.

They have also formed the Queer History South network that has brought together more than 350 historians, archivists, and community preservationists from 13 Southern states. It held its first conference in March 2019 and plans its second in 2022 in Dallas, having to postpone it from its original dates next February due to the COVID pandemic.

The Memphis archive has also had to postpone its plans due to the health crisis. After hosting a one-day symposium last fall, which marked its official coming out to the public, it had hoped to participate in various community events this year to increase its visibility and meet people willing to donate their materials or tape their own oral histories.

It is advising the local Pink Palace Museum on an expansive LGBTQ history exhibit the natural history museum plans to open in 2022.

“It would be lovely one day to have a Mid-South LGBTQ+ Museum,” said Byrd, “or at least an exhibit we can send around to local institutions.”

Meanwhile, both archival efforts continue to collect materials and oral histories from LGBTQ Southerners. They have helped preserve dozens of collections to date.

“A lot of the time we are convincing people, especially elder queer and trans folks, they are historically important,” said Sullivan. “They don’t think of themselves that way.”

Diversity is key

Sullivan and Burford have recruited a diverse board of directors to advise them on the archival project and ensure it encompasses more than just white, cisgender LGBTQ history. They have helped to digitize the records for Birmingham’s Black Pride organization.

Another project they are working on is doing oral histories with Black queer and trans individuals in conjunction with the Margaret Walker Center, an archive and museum at the historically Black Jackson State University in Mississippi.

“It is all part of this web of Deep South history we want to collect and highlight,” said Sullivan.

The Memphis archive plans to form its own community advisory board to ensure it is hearing from and working with diverse voices.

“We are all ready for the pandemic to subside. We were gaining some momentum, then this hit and put everything on hold,” said Byrd. “As soon as we can get back to this we will start collecting in earnest and getting the community involved and growing this collection. We want it to be more reflective of the community too and not just portions of it.”

To learn more about the Invisible Histories Project, visit its website at https://invisiblehistory.org/.

To learn more about the Mid-South LGBTQ+ Archive, visit its Facebook page at https://www.facebook.com/901LGBTQArchive/.

Matthew S. Bajko is an assistant editor with the Bay Area Reporter.