If you want to know how musical chameleon Shamir is doing right now, expect the 25-year-old to answer much like he approaches making music. In both cases, he doesn’t like to repeat himself. “I’ve done a lot of interviews, so I’ve been trying to vary my answers,” he says, laughing.

On the day we connect by phone, he’s not good, he’s not bad. “I’m alive, you know.”

Considering his 2020, which has been one of his most successful years yet, that’s a very good thing to be. In March, just as the United States shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic, the Las Vegas-born, Philly-based musician, known for his exploratory DIY style, released “Cataclysm.” It wouldn’t be his only album of the year.

Six months later comes “Shamir,” his first self-titled album and, it’s obviously worth noting, his seventh altogether, all released within the five years since his 2015 breakout “Ratchet” dropped on the same label as Adele and garnered him prestige in the pop music world.

Shamir, who identifies as non-binary and is open to being addressed by any gender pronouns, went on to release two albums in 2017, “Hope” and “Revelations.” Then came 2018’s “Resolution” and 2019’s “Be the Yee, Here Comes the Haw”. Genre-wise, his outside-the-box work is whatever he wants it to be, from pop to punk to country-inflected indie rock.

With “Shamir,” his second album of 2020 on his own label, he modernizes the lo-fi, women-led alt-pop-rock sound of the ’90s. At this point, he finds a way to do what he wants, when he wants, with nothing stopping him. Not a label, not a producer. Not even a global pandemic.

Is it a weird juxtaposition to be successful amid chaos and crisis?

Definitely. But knowing the way my life works, it makes total sense.

In other words, for you, this is just another year?

Well, success in the middle of a pandemic? That’s who I am. Anytime anything great happens to me, there’s always a catch. If you think of my most successful era, “Ratchet,” yeah, that was my most successful release “but” it was in a genre I didn’t want to do, had no business doing, and didn’t even fucking understand. (Laughs.)

Considering the artist you’ve evolved into, I wondered how you looked back at that era. Can you talk about the artistic journey you’ve been on?

It was just all natural. I completely removed myself from electronic-based pop music. I had to go back to being behind the guitar because before that record that’s what I was doing. It was weird to see me sing without my guitar, and I think I kind of did the pop era as a way to prove to myself that I could step back from behind the guitar, and I did and I did it successfully. But I realize that it didn’t make me happy. And I’m happiest behind the guitar. I enjoy songwriting more that way, and I realize that, well, this is my job now, and my life now. (Laughs.) I have to do it how I want, in a way that make me the most comfortable

With this being your first self-titled album, I wondered if the significance of that is that this is you at your purest.

It’s exactly that. Not even necessarily me at my purest, but it’s how I always imagined myself. It applies to every element that I love, because I do like to listen to electronic pop music and I am inspired by it, but I love playing guitar and I love grunge and I love indie rock, but I also love country and I also love punk. I think this record encapsulates all of that but also makes it digestible for anyone who likes any genre of music, really.

You seem more proud of this work than any albums you’ve done in the past. Is the feeling that you have now about this title different from, say, the feeling you had during the “Ratchet” release?

Yeah. I feel different after every release. I think I only make records when I’m in a fairly transformative time in my life, and with every record, I can pinpoint what I was doing in that section of my life, what I was feeling, and where I was mentally and physically. I think it just varies with each release. Obviously this release is so different. Even if I wanted to kind of treat it like every other release, I can’t just by virtue of releasing it in the middle of a pandemic (laughs). Everything I release is so different, and I’m in such a different mindset. I just got through this year relatively very sober – the most sober I’ve ever been. I mean, not necessarily on purpose but kind of. And also last month was a year since I last had a cigarette and quit smoking, so yeah, pandemic aside, I feel like a completely different person just from those two things.

It sounds like you are finding personal fulfillment by controlling what you can even if the world is falling down around you.

Yeah. This is the first record where I was “not” having a cigarette break between each vocal take. (Laughs.)

That’s progress.

My last engineer would joke because I’d do maybe a few vocal takes and then be like, “OK, I need to take a break and have a cigarette.” He’d call it my “vocal warm-ups.” I hear a difference in my voice. I’m sure other people can’t, but there’s a certain clarity that I’ve never heard.

When it comes to making music, how did you learn to do so much on your own?

I kind of have this jack-of-all-trades personality trait, and I don’t care to find out how something is made unless I feel like I can do it myself.

Did you learn anything new while making this album?

No, not necessarily. I’m such a jack of so many trades now at this point. (Laughs.)

There’s nothing more to learn!

There really is nothing more to learn, and if anything, it just kind of makes things more efficient. We made this record in only two weeks.

You’ve really cultivated a space for yourself in the underground pop music world, and I’m not sure how to best ask this question, but do you feel like your white gay contemporaries get more credit?

People love to ask me that. I will say this: No one can deny that if I was white my career wouldn’t look different. A perfect example is how (British musician) Scott Walker died not too long ago and I did not know about him until he died, and I felt such kinship because his career trajectory was very similar to mine in the sense that he started off as a teen pop singer who kind of had a hit but then that wasn’t his vibe so he started to do more avant-garde stuff. No time throughout my career did anyone compare me to Scott Walker, but yet a lot of people who knew Scott Walker compared me to Prince. Why were you comparing me to Prince? (Sarcastically.) I wonder why! You really have to think about that. I would be looked at completely differently if I was a white artist just in general, straight or gay or anything. Also, Black people are just expected to be exceptional because to make it anywhere as a Black person you have to be exceptional. It’s kind of just expected of us. That’s why sometimes…I’m gonna say this on the record, but if you take this quote out of context, I’m gonna fight you. (Laughs.)

There will be no fight, I promise you.

I don’t need the Beyhive comin’ for me. But I love Beyoncé. Beyoncé is honestly one of the greatest performers of all time. It is not her fault that she is one of the greatest performers of all time. I’m not trying to chastise her for being as great as she is. But a lot of people think all Black people need to be on the level of Beyoncé or they’re not shit. And that’s not her fault; that’s structural racism. So we gotta be on the level of Beyoncé to be seen as exceptional. Beyoncé is just un-human-level exceptional. For anyone. But because she’s a Black woman and because she’s Black, if Black people aren’t touching that, then it’s just like, “Why should we care?”

It seems Beyoncé has become the go-to name for Black artists in the sense that white people I think go, “Is it really a race problem? Because look at Beyoncé. She’s made it.”

And in a way, it’s kind of ridiculous that she’s had to get to this level to get to the level of success that she’s had when someone like…I love Britney Spears. Britney Spears is great, right? But Britney Spears did not work as hard as Beyoncé. But they’re seen on the same level. Yes, Britney worked a lot and everything, but the way that Beyoncé…Beyoncé never lip synced! The mic is always on!

What other challenges have you faced in the music industry because of who you are as a non-binary Black artist?

Producers undermining my taste or what I want, just in general. Not listening to me. That’s obviously really hard.

Is that one of the reasons why you sought autonomy?

That’s definitely one reason. Because I really don’t like confrontation. I’m the type of person who, a lot of times, would rather put my white flag up than really fight for something that feels frivolous in the grand scheme of things. One of the main reasons why I didn’t work with any producers (on past albums) is because every producer that would be willing to work with me already because of “Ratchet” had a preconceived notion of the type of artist I was and really couldn’t see past that. So I had to go and create this whole new world for myself to show the world and the industry what I’m becoming and kind of give them the picture of what I am doing. So I had to self-produce those records myself, and I was hoping that, out of that, a producer will hear them and eventually come to me. That’s what happened with Kyle (Pulley) who produced five tracks, and I recorded most of it at his studio. He liked my artistry and what I was doing as opposed to being, “This person has a cool, unique voice. I want to basically use it to further my ideas.”

It’s a shame it took so long to find a producer to honor your vision.

Yeah, it is a shame. But, honestly, that’s my life. It’s sad. But I can be sad about it or I can just pick myself up by the bootstraps and just do everything. Again, the jack-of-all-trades thing, it also comes from it being kind of a necessity at this point. I would get nothing done if I waited on people to help.

There were so many times in the recording process where I would override a decision and Kyle would just be like, “OK.” There was not a back and forth. I did not have to fight someone. I used to get in spats with the producer of “Ratchet,” honestly, to the point where at the end of the day of recording, I just gave up. I just didn’t care. I was like, “This is not my record anymore.”

What was the motivation behind the aesthetics for this project?

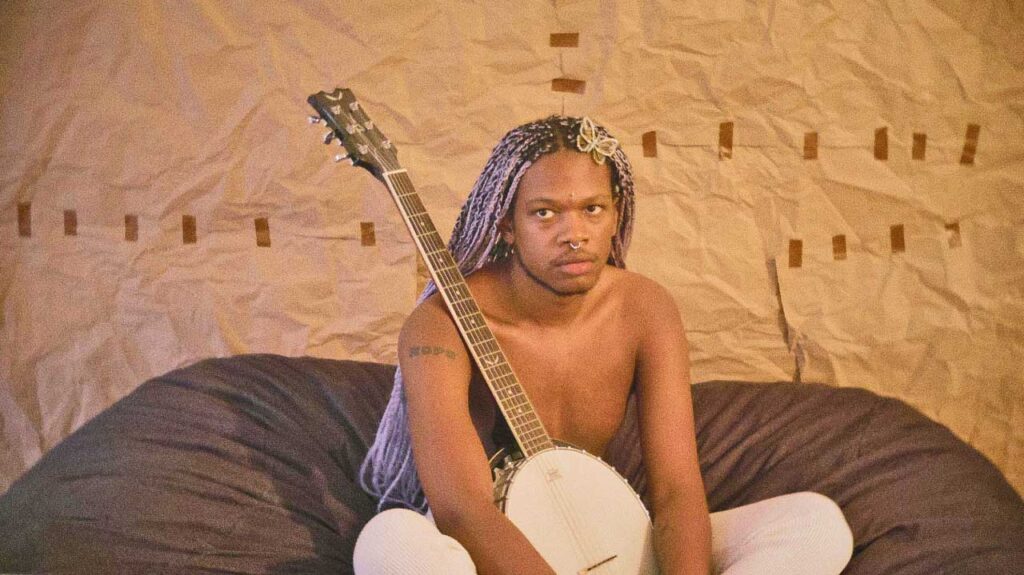

This was the first time where I kind of really felt like everything artistically did come with intent. I knew I wanted to have purple hair for this run (laughs). That came to me just in a vision. And I have spent all of last fall perfecting the very digital vintage look with the covers and the videos and the “On My Own” video. That video is very straightforward. It’s simple but it relies a lot on aesthetics, which I really loved. That was really fun for me, just styling and makeup wise. “I Wonder” was inspired by Keith Haring. So I think this, of all eras, was the most thought out artistic-wise.

How did you land on the blue nightgown for the “On My Own” video?

I got that last summer in Seattle at a thrift sale at a pop-up shop. I just literally had it lying around, and I’m glad I got to immortalize it.

You’ve released seven albums in five years. How do you do it?

I write like a crazy person.

Do you write like a crazy person for any particular reason?

Because I “am” a crazy person. (Laughs.) I work so fast. It doesn’t actually take up a lot of my time, and that’s why I’m like, “Oh, I’m gonna start a label and work with other artists and do 50,000 other things.”

How do you create so prolifically without repeating yourself?

Because I approach every record completely differently. “Ratchet” was made in a basement with one other dude, and then “Hope” was made in the middle of a manic episode in a weekend, and then “Revelations” was made after I got out of the mental hospital and had nothing to do but stay in my aunt’s house because I wasn’t allowed to do anything else. I just approach everyone differently. I don’t produce the same way each time or try to figure out what worked, what didn’t. I just want to make something that sounds good and feels cohesive.

You leave a lot up to where you’re at during that moment, both physically and mentally.

The outside elements, basically. Which is how life is. I think art should flow in that way too.

But you could’ve just made “On the Regular” over and over.

I could have, but it wouldn’t fulfill me. That would’ve fulfilled my bank account, sure. (Laughs). And that’s really important for me. I’m not a materialistic person at all, unfortunately. I wish I were because I’d be rich by now. I wish I were a materialistic, capitalistic-ass person, I really do. I don’t like being this queer communist fool. Honestly, I’ve been bamboozled most of the time, but I can’t help it. I was just raised like that, and this goes back to my jack-of-all-trades personality, but I’ve always felt more wealthy with the knowledge that I have, and (with) what I can do.

As editor of Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ wire service, Chris Azzopardi has interviewed a multitude of superstars, including Cher, Meryl Streep, Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.