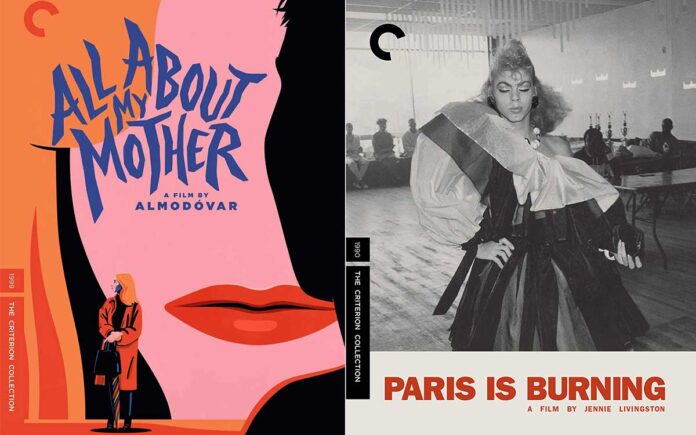

“Paris Is Burning”

In “Paris Is Burning,” a strut is a defiant act, an exertion of suppressed power. In the mid-to-late 1980s, when the landmark documentary was filmed, these moves couldn’t be showcased just anywhere. Today the same is true, as the call to end violence against trans people and to confront transphobia persists. Given the number of trans people killed since the doc was released (and the surge of trans murders currently making headlines), that call seems, still, to fall on deaf ears. And so white, queer, non-trans director Jennie Livingston’s 1990 film remains fiercely important, as much a time capsule as a reflection on how much progress has been made (and has yet to be made), its haunting relevance resonating yet again during our modern LGBTQ and Black Lives Matter movements.

At the time of its release, Livingston’s film illuminated issues of transphobia, racism, AIDS and poverty through intimate, everyday depictions of legendary voguers, drag queens and trans women, including Pepper LaBeija, Dorian Corey and Venus Xtravaganza, as they found both refuge from the oppressive outside world and a unifying sense of community within the drag-ball scene. “Paris Is Burning” introduced shade and voguing; it was the doc that opened the door for TV’s groundbreaking trans-centric show “Pose” and Netflix’s new doc on trans depiction in media, “Disclosure”, which acknowledges the classic doc’s historical significance while also critiquing it for being exploitative of a seriously marginalized community.

The Criterion Collection’s digital restoration of the film features: an episode of “The Joan Rivers Show” from 1991, with Livingston and ball community members, who teach Rivers queer slang; a new sit-down with Livingston, Sol Pendavis, Freddie Pendavis and filmmaker Thomas Allen Harris; and over an hour of never-before-seen footage. “Now more than ever, the call for realness, that reverberating standard of ball excellence, is required,” writes Black LGBTQ activist and filmmaker Michelle Parkerson in an essay in the 38-page liner notes of the Criterion release, which also includes a 1991 review by the late, Black gay poet and activist Essex Hemphill. In 2020, the film’s urgency can be heard loud and clear: our greatest act of defiance, it reminds us, is living authentically, for the whole world to see.

“Portrait of a Lady on Fire”

Forbidden love flourishes in the quietest of corners, outside of view, beyond the patriarchal pressures of the conformant. So it goes in writer-director Céline Sciamma’s achingly beautiful, queer-feminist love story “Portrait of a Lady on Fire”, where fire, often in a literal sense (there is lots of actual fire), burns fiercely and freely between two women, one an enamored painter, the other her reluctant subject. Sciamma sets her story in the late 18th century, during the dawn of the Romantic era.

A young painter, Marianne, played by French actress Noémie Merlant, arrives on a remote island off the coast of France to paint Heloise, played by French actress Adèle Haenel. The portrait is to be her wedding portrait, but Heloise doesn’t want to marry the man she is about to wed, so she refuses to pose. As Marianne’s relationship with Heloise blossoms, it’s clear she will have a better chance at capturing Heloise than the previous portrait artist, who left without accomplishing the task of painting Heloise. But Marianne is different, patient. She draws Heloise from memory in secret until she establishes her trust; she speaks to her in a way no one likely ever has, her attraction expressed fervidly through sometimes nothing more than small, stolen moments when she fixes her enraptured eyes on Heloise.

Aesthetically, the film is a ravishing work of art all its own, a kind of visual poetry that cinematographer Claire Mathon captures to breathtaking effect. In stunning 4K, Criterion emphasizes the sumptuous beauty rendered in each scene. Beyond the film itself, the Blu-ray includes a new conversation with Sciamma and film critic Dana Stevens, new interviews with Haenel and Merlant, and an interview with Mathon.

“All About My Mother”

In the 1999 Spanish drama “All About My Mother,” the celebrated gay film visionary Pedro Almodóvar’s reverence for women movingly permeates every vibrant frame of his loving ode to sisterhood. Self-assembled family units are, of course, a dynamic that is an-oft necessary way of life for members of the LGBTQ community, which “All About My Mother” honors through the character of Agrado (played by Spanish actress Antonia San Juan), an early figure of transgender representation, and the way in which Almodóvar matter-of-factly folds her into a blended family of characteristically diverse women. Those women include Sister Rosa (Penélope Cruz), an HIV-positive nun; Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes), an iconic actress; and the film’s grief-stricken protagonist, Manuela (Cecilia Roth), whose determination to stay connected to her teenage son after his sudden death leads her to discover the magic of chosen family and the healing bonds those relationships engender.

In a 1999 written tribute republished in Criterion’s digital restoration of the film, Almodóvar reflects on whimsical distortions of truth for the screen, and a perspective his mother shared with him as a child that became the impetus for “All About My Mother”, one that is hard to argue with: “how reality needs fiction in order to be complete, more pleasant, more livable.” Elsewhere, Criterion’s Blu-ray release includes a 52-minute documentary from 2012 on the making of the film, a TV program featuring Almodóvar and his mother, and a post-screening Q&A from 2019.

“The Prince of Tides”

Barbra Streisand has garnered far less attention for her work behind the camera than in front of it, even though she was instrumental in dismantling the status quo of male-dominated directors. And so her film “The Prince of Tides” rightfully deserves Criterion treatment, with all the bells and whistles presented here, including a stunning 4K transfer and lots of Babs. She is featured in several interviews, and provides a thoughtful audio commentary, recorded in 1991 and updated in 2019. There’s audition and rehearsal footage, behind-the-scenes footage and an alternate ending that features a song that Streisand wrote for the film called “Places That Belong to You,” cut from the movie so as not to distract from the film’s central character study.

Released in 1992, “The Prince of Tides” was Streisand’s second feature as a director, after her 1983 telling of “Yentl.” So emotionally invested in Pat Conroy’s novel of the same name years before its release, Streisand’s cinematic take on the story, which she also starred in and produced, scored seven Oscar nominations and traverses genre borders, from schmaltzy romance to family drama and, during the film’s most horrific reveal, a shocking thriller. The film features the multi-hyphenate living legend as Dr. Susan Lowenstein, a psychiatrist who unearths one family’s buried trauma. She does so through regular meetings with Tom Wingo (Nick Nolte) after his sister, Savannah, attempts suicide. Of note: George Carlin as Eddie Detreville, Savannah’s trusted gay neighbor, and Streisand’s gay son Jason Gould, who plays her son in the film. Moving through, and past, trauma is the film’s crux, until it makes a full-on soap-opera leap and centers the soppy love-conquers-all romance between Streisand and Nolte, undermining the drama’s stronger, more complex themes. What’s admirable, though, is how, nearly three decades ago, Streisand shined a light on the potential danger of toxic masculinity and nurtured a project that encouraged men to embrace sensitivity and vulnerability.

Chris Azzopardi is the editor of Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ wire service. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.