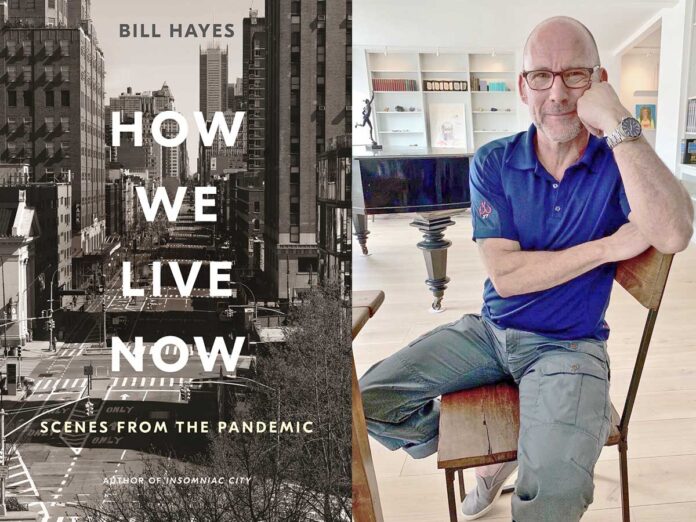

Out gay author and photographer Bill Hayes’ eloquent and elegant new book, “How We Live Now,” is subtitled, “Scenes from the Pandemic.” Hayes provides “snapshots” of life during COVID both in prose and in black and white street photos. (Check out his Instagram for additional images, including ones from the book in color).

His slim volume can — and perhaps should — be read in one sitting. But readers also may feel like they should wear PPE while holding it. “How We Live Now” is delicate both in its prose and content. Hayes’ writing is crisp, and several chapters are poetic. (None are more than a few pages).

The thoughts expressed in the short, snappy vignettes are reflections on life during lockdown. Hayes’ tone is elegiac, but he holds the reader’s hand through what he (and most everyone) is enduring during these uncertain times. This is not a survival guide — though to an extent it is; it is more like an undated diary, where days bleed into one another. He writes out an exercise regimen on March 18, 2020 and 25 pages later, he acknowledges a lack of motivation to exercise. Only nine days have passed.

Hayes misses the gym, and swimming. He is bored and restless in his solitude and living alone. (His husband, the neurologist and author Oliver Sacks, died in 2015). One of the first chapters is a list of 41 things he used to do, from “shaking hands with a stranger” to “falling in love.” This entry provides an ersatz table of contents as “How We Live Now” recounts Hayes’ thoughts and experiences about simple things like riding a subway, kissing someone, going out for a drink, or getting a haircut.

He mixes personal stories with observations. The approach works, because much of what Hayes writes is universal. He recounts the moment last Christmas when he met Jesse, his lover, in a bar and took him home. He reveals his weakness for Jesse’s gap-toothed smile and writes about kissing and kissing and kissing Jesse on New Year’s Eve.

Readers may be disappointed that Hayes does not include an image of Jesse, but then, several pages later, he does. It is an arty black-and-white nude entitled, “The Last Time I Kissed a Man,” dated March 14, 2020, 1:44 p.m. The gap-toothed smile is hidden under a pillow. The fact that such intimacy may not be recaptured for a long time is potent because their nascent romance is arrested by the virus. Despite a weak moment where they meet in person after lockdown, most of Hayes’ exchanges with Jesse are conducted via text or at a social distance. Hayes bemoans celibacy, and that he no longer needs to take PrEP. He longs for touch and human contact.

“How We Live Now” provides other impressions of life during quarantine. Hayes chronicles the eerie, enforced silence of New York City, documenting the change as Manhattan feels like “everyone has gone missing.” Whereas the subways have throngs of riders wedged tightly, “shoulder to shoulder, ass to ass,” he includes a photo of the “L Train at Rush Hour” at 5:05 pm, April 22. It is as empty as his photo of 8th Avenue on April 6.

Hayes writes briefly about depression, and he could have expanded more on that topic. His observation, “The most important thing I’ve learned about depression is not to think about it as ‘a depression,’ as if it were a single monolithic thing,” is practical, useful, but also vague. It would have been interesting to know more about how he coped with the bouts of loneliness under lockdown.

The book suggests he took walks, and met people, from a woman arranging a mandala, to a trio of residents in anesthesiology at NYU Medical Center, who all had COVID, sitting on a stoop, to the clerk at a local liquor store, who signs Hayes’ credit card in an amusing fashion. These are “New York moments,” and “How We Live Now” is full of similar enchanting stories. Hayes recounts having an illicit drink at a restaurant with the owner, Joe, when he swings by to pick up a food order. He hears a story from a friend who was kindly offered a tissue by a passing car, and he describes the response by his neighbor and doorman to prevent a naked man outside their building from being hit by a car or put in jail.

What emerges in these and other scenes is solidarity and humanity. Hayes is kind to a teacher from Philadelphia who inadvertently calls him. He gives money to Raheem, a homeless man he knows. And he reaches out and renews friendships.

A thread throughout “How We Live Now” is about chances taken and regrets for things not done. This provides the book’s most poignant, salient theme. Hayes describes taking a photo of a man he met on a subway, pre-COVID. The stranger tells Hayes he agreed to pose, “Because I never do things like this.”

Hayes’ book offers hope that we can experience such random, pleasurable moments of connection again soon.