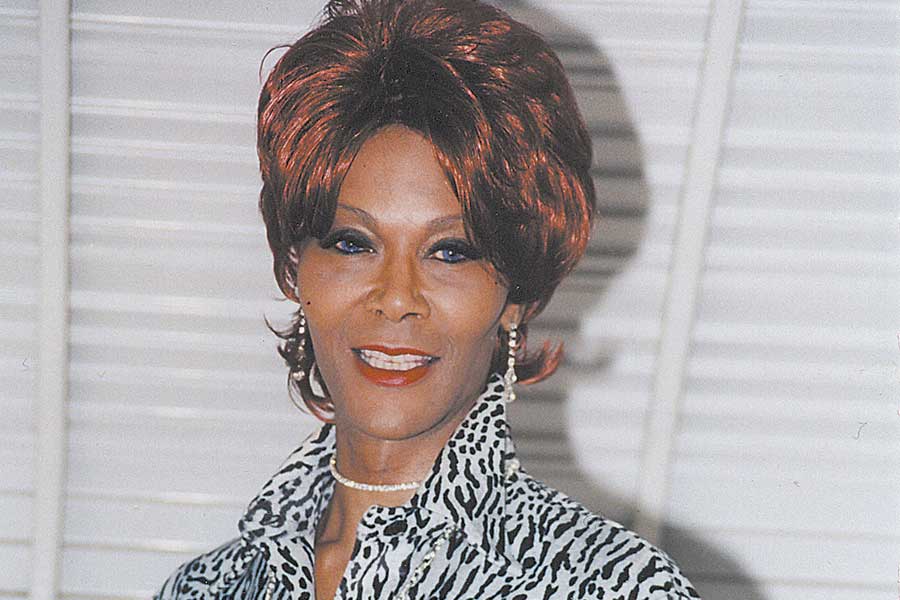

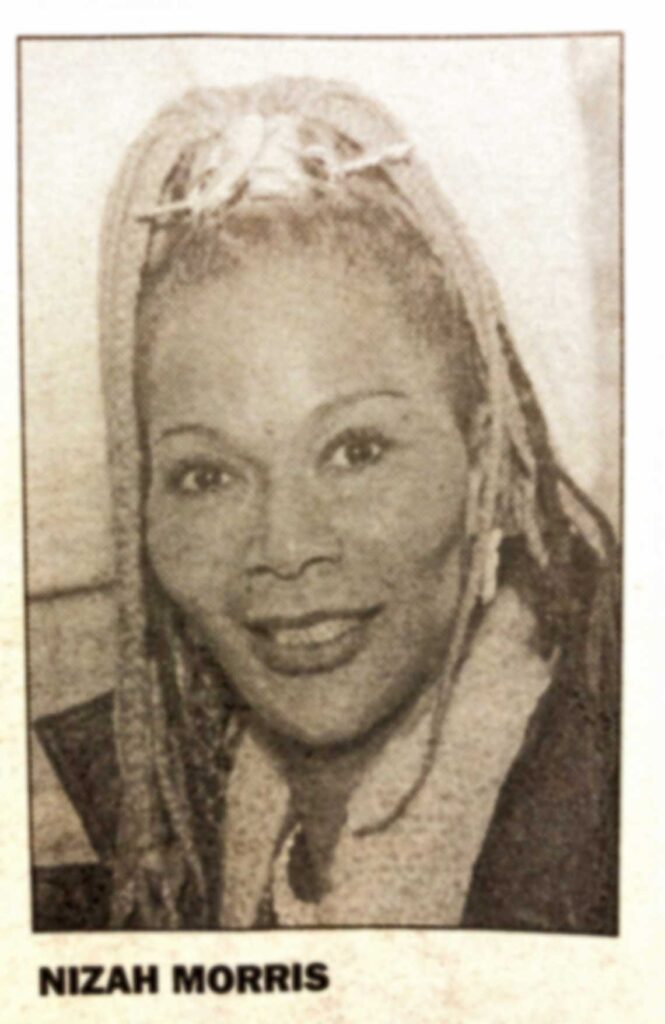

This month marks the 65th birthday of Nizah Morris. It’s difficult to believe that Nizah would be a senior citizen if she were alive today. She was born on Oct. 19, 1955. So much has changed since her tragic death in 2002 — possibly connected to an encounter with Philadelphia police. This year, 2020, marks my 17th year — and counting — reporting on her case. Today, widespread police-reform efforts are underway. But when Nizah was alive, many police officers believed they could brutalize the LGBT community with impunity.

At the time of her death, Nizah was a 47-year-old trans woman of color and a beloved figure in the Philadelphia community. She was a popular entertainer and advocated for transgender rights.

On Dec. 22, 2002, she attended a private party at the old Key West Bar, near 13th and Walnut streets. From all accounts, she had too much to drink at the party. Nizah was stumbling and falling outside Key West. At 3:07 a.m, a person identified only as “Anisa” placed a 911 call on Nizah’s behalf, seeking an ambulance because Nizah couldn’t stand without assistance. Officers Kenneth Novak and Elizabeth Skala were dispatched to investigate Nizah at 3:10 a.m. Paramedics were also summoned. Skala arrived first, canceled the paramedics, and told the dispatcher she would “drop off” Nizah at 15th and Walnut. Skala said this at 3:13 a.m., according to 911 tapes. (Skala later told investigators she thought Nizah lived at 15th and Walnut. But Nizah lived three miles away in West Philadelphia.) Novak’s movements during the “courtesy ride” for Nizah remain unclear.

Twelve minutes later, at 3:25 a.m., a passing motorist called 911, reporting that someone was lying unconscious in the street at 16th and Walnut, bleeding from the head.

Once again, paramedics were summoned. But when they arrived at 16th and Walnut, they acted strangely — speaking at length with Officer Thomas Berry rather than tending to Nizah, according to an eyewitness. A few minutes earlier, Berry had offered to help Nizah out of Skala’s car, but his help wasn’t needed, Berry later told investigators.

Nizah had a subdural hematoma and needed prompt medical attention if she were to survive. But when paramedics finally placed Nizah onto a gurney for transport to Jefferson Hospital, Berry put Nizah’s jacket over her face, as if she were already dead, according to an eyewitness.

Nizah died 64 hours later at Jefferson Hospital. She was alone. The police didn’t try to identify her and summon her family. On Dec. 25, 2002, the Medical Examiner’s Office declared Nizah’s death to be a “homicide” due to “blunt-force head trauma.” Several days later, when relatives were informed about Nizah’s “courtesy ride,” they became deeply concerned that police were linked to her death.

Police officials initially refused to accept that Nizah was a homicide victim. They retained a neuropathologist, Lucy Rorke, to review the medical examiner’s findings. Rorke reaffirmed that Nizah was a homicide victim. But a police spokesperson insisted that any suggestion that police were responsible for Nizah’s death would be “preposterous.”

My reporting of the case intensified in January 2003, when Nizah’s mother Roslyn contacted me and expressed concern that police killed her daughter. Roslyn simply couldn’t believe the story she was getting from police. I’ll never forget Roslyn’s question to me: “Since when are the police a taxi service?” As for Skala thinking Nizah lived at 15th and Walnut, Roslyn said: “Nobody lives at 15th and Walnut.”

Thus began a lengthy effort to answer the question: “Who killed Nizah Morris?” The first thing I did after Roslyn’s phone call was to request police reports for the pre-injury and post-injury incidents involving Nizah. I paid $30 expecting to receive two reports. Instead, I got a letter from police claiming no police report was written for either incident. This inaccurate information was sent to me via the U.S. Postal Service. I asked the police department’s LGBT liaison officer to look into the matter, but he was of no assistance.

After I wrote a PGN story about the police’s assertion that no report had been written about Nizah, her sister Andrea contacted me and said she saw a police report among the possessions of a homicide detective who visited Roslyn’s home.

I conveyed this information to PGN’s then-editor, Patti Tihey, who wrote an editorial calling for an FBI investigation of Nizah’s death.

Perhaps as a preemptive measure, then-District Attorney Lynne Abraham telephoned me after the editorial appeared and said her office would investigate the case. That happened in April 2003.

Abraham also told me that police did write an incident report about Nizah. She said I could pick up a copy at the 9th Police District in the Fairmount section.

Berry wrote the police report but wasn’t available to answer questions about it. I was dumbfounded when I saw that Berry speculated about Nizah’s LGBT status in his report. He wrote that Nizah appeared to be a “transsexual.” Police officers aren’t supposed to speculate about the LGBT status of a simple “hospital case” — which is what Berry deemed Nizah to be. Berry’s report was mystifying and increased my curiosity about the police response to Nizah.

In December 2003, Abraham announced that the DA’s Morris investigation reached an impasse with no criminal suspects identified — thus clearing the way for public hearings before the Police Advisory Commission (PAC) for possible violations of police department regulations. Due to protracted resistance from the police department, the hearings didn’t take place until December 2006.

The main thing I remember about the PAC’s 2006 hearings was Skala’s complete inability to distance herself from Nizah’s head injury. I will never forget this exchange between PAC Commissioner Adam Rodgers and Skala:

Rodgers: For the record, your best estimate is she’s with you for 16 minutes and you dropped her off?

Skala: Yes.

Skala’s 16-minute estimate placed her squarely with Nizah at the time of her head injury. Please remember: At 3:10 a.m. Skala and Novak were dispatched to investigate Nizah near 13th and Walnut. At 3:25 a.m. the first post-injury 911 call for Nizah was placed at 16th and Walnut. That’s 15 minutes after Skala and Novak were initially dispatched. If Skala was with Nizah for 16 minutes, she had to be present when Nizah sustained her head injury. Just do the math.

Also during the hearings, I was struck that Novak wasn’t called to testify. Nizah’s relatives implored PAC staff and commissioners to require Novak to testify. But for some reason never explained to the public, Novak wasn’t required to testify at the PAC hearings.

Computer-aided dispatch records released during the PAC hearings indicated that several Morris 911 transmissions had never been released to the public. That prompted me to file an open-records request with the police for a complete set of 911 transmissions relating to the Morris incident. The litigation ended when the police department acknowledged its entire Morris homicide file was missing. Mind you, the Morris case was receiving a fair amount of media attention at the time. Yet the police still managed to lose their entire Morris homicide file.

At PGN’s insistence, the city Law Department agreed to contact various city agencies in an effort to reconstruct the Morris homicide file. I was given a copy of the reconstructed file. Several city agencies contributed records to it, including the DA’s Office and the PAC. If additional Morris documents were located, they were supposed to be placed in the reconstructed file — which I would be permitted to access upon request. This agreement was memorialized in a stipulated order signed by Common Pleas Judge Jane Cutler Greenspan in May 2008.

In January 2011, I was pleased when a new group of PAC commissioners agreed to reopen the Morris probe. (The previous PAC cleared police of any responsibility for Nizah’s death.) The new PAC commissioners subpoenaed all Morris records at the DA’s office. In response, a contingent of commissioners was permitted to visit the DA’s Office and photocopy Morris records never revealed to the public. But due to a nondisclosure agreement, PAC commissioners couldn’t share the DA’s records with the public. Moreover, the records weren’t deposited in the reconstructed Morris homicide file, which in my opinion was a violation of Judge Greenspan’s order.

Still, the PAC’s second investigation was helpful because it unearthed an unredacted version of Berry’s report. The unredacted version shows that Berry made emendations to his report after visiting Nizah at Jefferson Hospital around 6 a.m. Dec. 22, 2002. Novak and Skala also were there. I don’t know why all three officers visited Nizah at Jefferson Hospital. But I do know their patrol logs and Berry’s police report document Nizah solely in the context of being a “hospital case.” My concern is that all three officers waited to complete their paperwork until they visited Jefferson Hospital and could write about Nizah in that context.

In doing so, the officers avoided documenting the courtesy ride and Nizah’s fatal head wound. Such details wouldn’t be necessary for a simple “hospital case” that was transported to a hospital by paramedics, not by police.

I’ve tried on numerous occasions to obtain clarity about the officers’ paperwork, to no avail. In my opinion, it’s outrageous that police don’t feel the need to publicly explain these official documents. Perhaps with the national movement for systemic police reform currently underway, an explanation will be forthcoming.

In 2013, the PAC issued a supplemental Morris opinion, calling for state and federal probes of the Morris case. So far, neither the U.S. Attorney’s Office nor the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office has agreed to investigate the matter. Attorney General Josh Shapiro has stated publicly that he would review the case if the legislature gives him the power to do so. As of presstime, no such legislation has been introduced.

In 2014, I was honored by the Society of Professional Journalists with a Sigma Delta Chi Investigative Reporting Award for my coverage of the Morris case. I will always remember the trip to D.C. to receive the award, accompanied by PGN Publisher Mark Segal and then-Editor Jen Colletta. It was the first time an LGBT media outlet had been honored with a Sigma Delta Chi award. The recognition was deeply appreciated and helped shine a spotlight on the case. I hope that Nizah was looking down, smiling.

The struggle for transparency in Nizah’s death continues to this day. The Edelstein Law Firm recently was retained by PGN to help enforce the stipulated order signed by Judge Greenspan in 2008. It is hoped that city officials will cooperate with the order and deposit all of the city’s Morris records in a reconstructed homicide file — without the need for additional litigation.

Julie Chovanes, a civil-rights attorney and transgender advocate, is also trying to bring transparency to the Morris case. Thanks to Chovanes, the police department released its Morris Internal Affair Bureau file in July 2018 — a huge achievement which the city resisted for many years. Chovanes is currently seeking all Morris records at the DA’s Office. Her open-records request remains pending in Commonwealth Court.

The Morris saga is far from over. Many questions remain: Why couldn’t Skala distance herself from Nizah’s head injury at the PAC hearings? Why didn’t Novak testify at the PAC hearings? Why did Berry place a jacket over Nizah’s face as she was clinging to life? Why did all three officers visit Nizah at Jefferson Hospital? Are local authorities pursuing justice or perpetrating a cover-up?

Releasing the city’s Morris records could potentially answer many of these lingering questions. Judge Greenspan didn’t see any danger with transparency in 2008. I don’t see any danger with transparency in 2020. Information is power. As I told DA Larry Krasner not long ago, transparency in the Morris case would be akin to applying Mercurochrome to a festering wound. Then, the healing process can begin.