“Oliver Sacks: His Own Life,” available in virtual cinema via kinomarquee starting September 23, is a fantastic, inspiring tribute to the late gay neurologist and bestselling author.

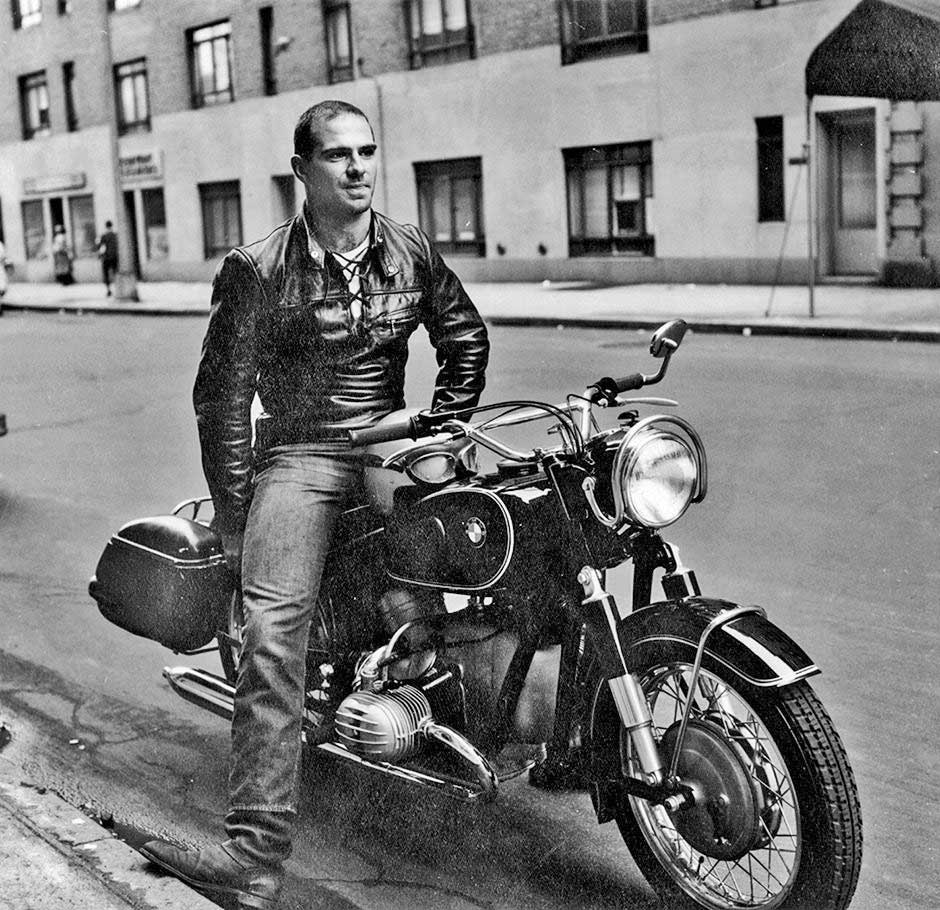

Director Ric Burns’ documentary takes the traditional portrait approach, covering Sacks’ early life. He grew up Jewish in a family of doctors in England, had a schizophrenic brother, and his coming out prompted a horrible, painful response from his mother. He eventually moved to America, taking up bodybuilding, motorcycle riding, and consuming a myriad of amphetamines while also working in various hospitals.

Throughout his life, Sacks mostly focused on his work, humanizing patients with sleeping sickness, Tourette’s Syndrome, and other misunderstood disorders, which eventually made him a household name and author. While he had some sexual experiences — one with a straight roommate is revealing — he was celibate for 35 years. Then, in his seventies, he met his partner and love of his life, Bill Hayes.

The lack of respect Sacks received from the medical community rankled him, but his ability to publish books with case studies of patients that made these individuals feel more accepted and less “other” was the key to his success. The impact his work had on a generation of students is a testament to his genius.

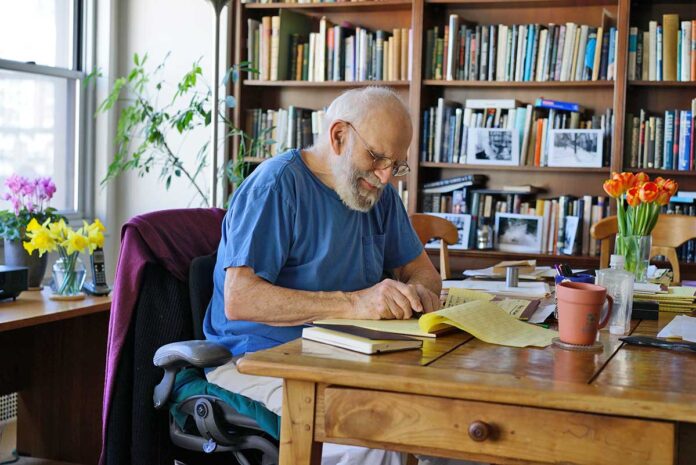

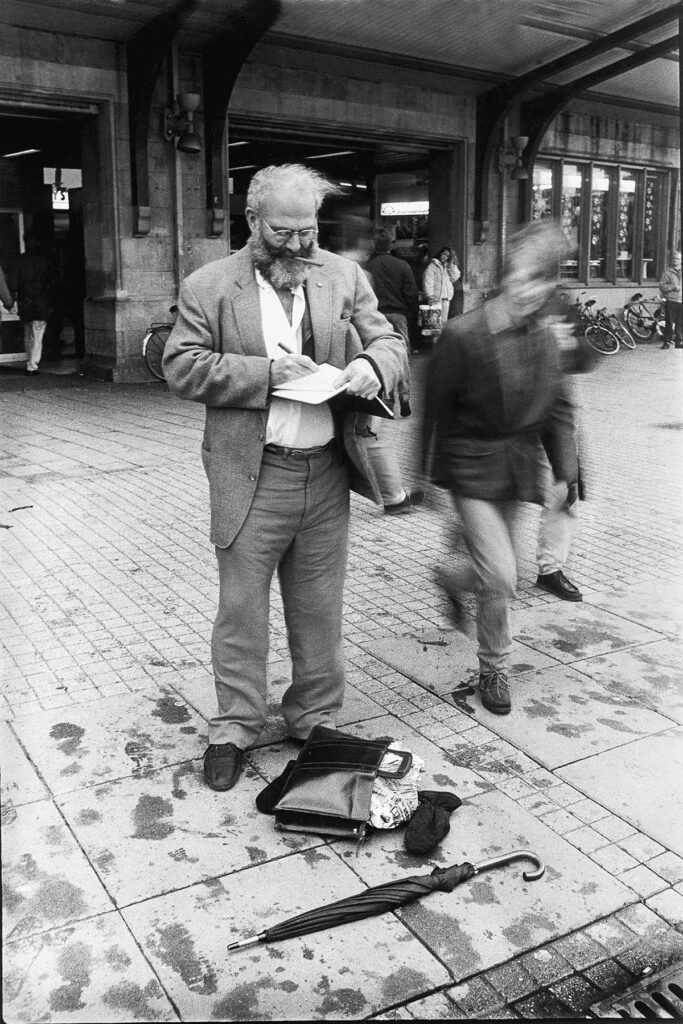

Burns illustrates these aspects of Sacks’ life and work through charming scenes of the late doctor as well as archival photographs and interviews with Hayes, his friends, colleagues, and peers.

In a recent Zoom chat, Bill Hayes, Sacks’ widower and author of the new book, “How We Live Now,” remembered his late husband.

Sacks is seen in the film as being funny, shy, self-deprecating, and even self-destructive. Knowing him as you did, how would you describe him?

He was very shy, throughout his whole life, but paradoxically, he had another side to him. He was very extroverted and a performer and once he got in front of an audience to give a lecture, or teach a class, he could come out of his shell. Every day and every night with Oliver was interesting. He had constant energy. He was so curious. He was extremely productive. Even when he got a terminal cancer diagnosis, it didn’t divert him. He had so many interests beyond writing. If he wasn’t writing, he was thinking or reading about or exploring botany, minerals, elements, the periodic table. Keeping up with him was sometimes a challenge. He was hilarious and quirky, and by his own admission he was eccentric and hypochondriacal. That is the Oliver I knew in our six years together, and that is the Oliver of the everyday. He was charming, brilliant, hilarious, eccentric, empathetic, all those things.

What observations do you have about your relationship with Sacks?

There was about a 30-year age difference, and Oliver had never been in a romantic, domestic relationship before, whereas I had. We had this immediate rapport when we first met in person. He was unlike anyone I ever met. In the 5 years since his death, I’ve come to appreciate how amazing he was even more. We first connected as writers. He read my book, “The Anatomist,” which tells the story behind “Gray’s Anatomy.” He wrote me a letter, which I later learned, was not uncommon for Oliver. But for someone, like me, to get a letter from Oliver Sacks was pretty fucking amazing. I wrote back, and to my surprise, he wrote a letter back. We had a brief collegial correspondence. I didn’t know if he was gay or straight. I moved to New York — not to be with Oliver — but when we met, the chemistry was undeniable, and we fell in love pretty fast. We had many interests in common, but we also taught each other new things. I got a crash course in neurology, neuroscience, psychology, the periodic table, and botany, but I introduced Oliver to what it is like to be in a domestic and romantic relationship. There was a balance.

The film shows the shame, stigma, and secrecy he experienced as a gay man, but also the way he helped patients who were seen as “other.” It was his status as an outsider that made him empathetic, and he allowed his own experiences to inform his work. What are your thoughts on his approach to his work?

There are many aspects to the unusual empathy he had for his patients. But I do think there’s another word that’s equally important, that applies not only to his patients, but to Oliver as a person, and that is curiosity. That’s an important ingredient in how he got into his patients’ lives. He used to say he tried to imagine himself in the lives of his patients.

Sacks was very obsessed with classification. You state in the film that he carried a periodic table in his wallet. Yet he struggled to classify himself as a doctor or a writer. Why did he seek order?

I’m not sure there is an answer, but part of it is rooted in his chaotic and confusing childhood, being sent off to a boarding school during the Blitz. I think he found comfort and solace in the order of numbers, the periodic table, and the rationality of science. That helped him make sense of the world. He also naturally had that interest, coming from a brilliant family of physicians. That was a part of living with Oliver, which was wonderful. You could throw a number to him and he could tell you the history of the discovery of that particular element in the periodic table. He was known for giving the element from the periodic table that matched your birthday. When I turned 50, he gave me tin. He loved to do that for friends if he could afford it, or it was safe — because there are some elements that are not safe to give to a friend as a birthday gift.

I like that you recognize his survival skills, that he found ways to cope with a world that did not always appreciate him. Can you talk about that quality, and what he taught you in your time together?

This goes back to his intense curiosity about the world and going to extremes to explore what interested him; taking risks — driving to the Grand Canyon overnight and taking handfuls of drugs. Survival as a theme runs throughout his whole work, like his interest in ferns and the patients he was devoted to. He was kind of a survivor as a writer as well. He did not really become famous until “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” when he was 52. It was the latter part of his life that he had that kind of recognition. For me personally, living with him, just seeing that example, was really inspiring. I had not achieved that kind of success. He certainly didn’t get much recognition from his colleagues as a neurologist.

Sacks is said to have been “ahead of his time” in one interview. What do you think his legacy will be?

I think his greatest legacy was that he normalized the idea of neurodiversity. Although he didn’t coin the term, which is common nowadays, he normalized the idea that there is a whole spectrum to neurodiversity. These are not diseases, but differences in how we live as human beings. His writing about autism or Tourette’s syndrome — those were the two chief disorders he surfaced through his writing, not only by identifying them, but by humanizing those who have those syndromes. I hear people say that by reading Oliver, or hearing him talk, it makes them feel they are interesting in their own ways, and different, but not bizarre, or diseased, or crazy.