In the peppy documentary “House of Cardin,” fashion designer Pierre Cardin is described as “a label, a logo, and a legend.” This celebratory film, available on demand September 15, collages interviews, observational and archival footage, and hundreds of photos of fabulous fashions, to showcase the designer’s work and life.

Directors P. David Ebersole and Todd Hughes start by tracing Cardin’s early life. He was born in Italy and went to France at 16. He interned as a tailor at first and worked at Dior at age 20. He also designed costumes for Jean Cocteau’s 1946 film, “Beauty and the Beast.” Being young and good looking, he was desired by many admirers. The directors hint that the gay filmmakers Cocteau, Luchino Visconti, and Pier Paolo Pasolini all wanted to sleep with him, but Cardin’s sexual relationships are saved for later discussion.

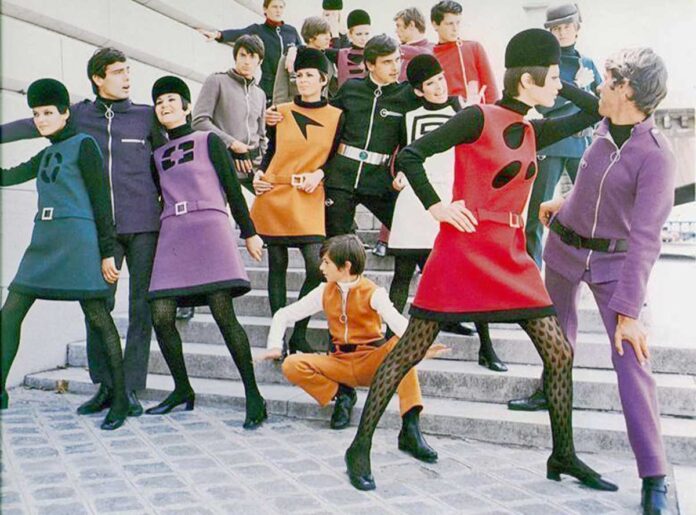

Instead, the film’s early focus is on the designer’s style. He created a “bubble dress” that got him noticed. The fashions Cardin made were chic and modern. He shifted from haute couture to ready-to-wear — which may be at the root of the jealousy between Cardin and fellow designer Yves Saint Laurent. (The filmmakers don’t address this too closely.) Cardin eventually developed a men’s collection and even modeled some of the clothes himself. The documentary indicates that male models at the time were assumed to be gay, so this was a bold move.

Cardin made other bold moves, which the film suggests is why he is so deserving of reverence and attention. In the 1960s, he hired Hiroko Matsumoto, a Japanese model. Ever a trendsetter, Cardin hired a number of diverse models, the filmmakers announce proudly. “House of Cardin” even pauses to ask queer model/actress Jenny Shimizu about the importance of this, and she explains that such representation (or lack thereof) was partly why she decided to become a model herself.

These and other anecdotes reinforce how Cardin was focused on the youth market. His designs freed women’s bodies, and as a result, his clothes empowered females. He thought about men’s suits differently and designed clothes for The Beatles. His fashions were hip and fun and as the barrage of images of dresses and suits show, they were also gorgeous.

“House of Cardin” is exciting as it breathlessly recounts all of Cardin’s achievements. When he moves into designing furniture, with Philippe Starck, no less, the designer gets futuristic. Soon Cardin is propelled into designing eyewear, and eventually becoming a brand, with Pierre Cardin cologne — in a “chic bottle that looks like a penis,” one interviewee observes. He even designed both an AMC Javelin car and an executive jet. Sure, the Pierre Cardin name is overexposed at this point, but the designer made so much money he could buy or do anything he wanted. And he did. In one of the most interesting purchases, Cardin buys the Art Nouveau restaurant Maxim’s — an establishment that once kicked him out for not adhering to the dress code.

“House of Cardin” almost overwhelms viewers with information about Cardin’s trips to China and Japan, where he revolutionized fashion in areas that were practically monochromatic in color and style. He established a theater, Espace Cardin, where he hosted various concerts including ones by Marlene Dietrich, Dionne Warwick, and Alice Cooper. And yes, a riot broke out when Cooper played, which the performer cheekily insists is why Cardin booked him.

Cardin, the filmmakers assert, is all about finding pleasure in his work. Nearing 100, he is still keeping busy, a quality most of his staff admire. The film does not provide many insights into its subject — that is not its intent — but one nugget they do get is Cardin admitting that he gets bored on vacation. Another is that he is proudest of receiving an award from the Académie de Beaux-Arts, the highest honor in France.

“House of Cardin” largely avoids Cardin’s personal life save a discussion of his relationship with actress Jeanne Moreau. Cardin designed costumes for several of Moreau’s films, including “Bay of Angels,” and they apparently “dated” for a while, much to the chagrin of André Oliver, Cardin’s partner. The film could have addressed his romantic relationships more, but perhaps Cardin’s participation in the documentary is why it is so congratulatory.

The upbeat tone is not much of a drawback. It is fun to hear Naomi Campbell gush or see Sharon Stone modeling a Cardin dress. Jean-Paul Gaultier, who worked for Cardin in the 1970s, talks about his mentor, and other designers, like Trina Turk, address his influence.

“House of Cardin” is an effusive, appreciative look at the designer that focuses on the clothes (and other things) its subject created and the impact they had on the world in general and the fashion world in particular.