This past July, when Dr. Rachel Levine, the Pennsylvania Secretary of Health and a trans woman, was cruelly mocked at a dunk tank at the Bloomsburg Fair in rural Columbia County, fifty LGBTQ organizations from across the Keystone State immediately demanded an apology.

This isn’t the first time that the Bloomsburg Fair, which was begun in 1855, has crossed the line between family fun and anti-LGBTQ animus. In 1978, Anita Bryant, a former pop singer turned anti-gay activist, brought her “Protect America’s Children” campaign to the fair.

Unwilling to let Bryant’s views go unopposed, Dan Maneval, who cofounded the Homophiles of Williamsport along with Gary Norton, quickly organized a counterprotest. Other groups, including the Pennsylvania Rural Gay Caucus, joined them. In addition to making their views known at the fair, the activists garnered surprisingly good coverage in the local media. Television stations in the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre area even broadcast a clip of Maneval’s speech.

All told, the counterprotest was a success. In the aftermath, however, Maneval’s family home was repeatedly vandalized. Recognizing that the local police would be no help, he sold his house and moved away.

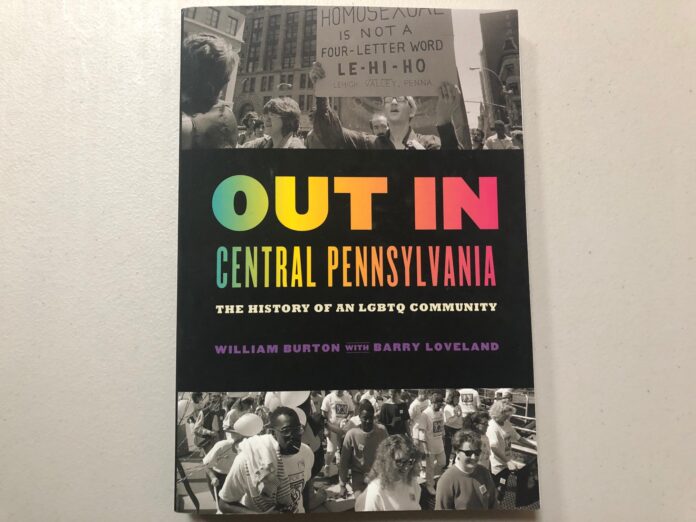

That’s just one example of the bold initiatives undertaken by LGBTQ people recounted in “Out in Central Pennsylvania: The History of an LGBTQ Community.” The book, written by William Burton with assistance from Barry Loveland, focuses on LGBTQ life in the small cities and rural towns scattered in and around Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Valley. It unfolds in roughly chronological order, from the late 1950s to the present.

Although the people Burton and Loveland write about don’t live in big cities and are largely unknown to the general public, their lives — and accomplishments — are noteworthy. As the authors put it, “With no laws to protect them, no distinct LGBTQ neighborhoods in which to live, and no centralized space to congregate, they collaborated to find inventive ways to form social networks and organizations, fight successfully for civil rights protections, and build a dynamic community.”

One highlight of “Out in Central Pennsylvania” is its profiles of individuals like Lorraine Kujawa. Kujawa, a schoolteacher in Dauphin County, was instrumental in creating the “Lavender Letter,” a monthly newsletter of social events for lesbians that circulated in the early 1980s. These stories of coming out, cruising, and creating an LGBTQ community add memorable personal detail to the book.

Another highlight is the more than 80 black-and-white images that populate the book. Some record significant events like the photo from Harrisburg’s first gay rights demonstration in 1977. Other images preserve ephemeral artifacts, such as a pin marking the seventh anniversary of the Pennsmen, a gay leather group from Harrisburg.

But those personal anecdotes and quotidian details exist in a broader context that includes both hard-won achievements and daunting challenges for LGBTQ people more generally. In April 1975, for example, Governor Milton Shapp issued an historic executive order banning employment discrimination against LGBTQ employees working within the state government. The need for that remedy was brought to Shapp’s attention by LGBTQ activists, including PGN Publisher Mark Segal.

Shapp then signed a second executive order in February 1976 that created the Pennsylvania Council for Sexual Minorities. For LGBTQ employees working in state government, especially those in Harrisburg, these were welcome developments.

Despite such victories, change was slow in coming to small cities throughout central Pennsylvania. In January 1993, for example, York mayor William Althaus proposed a local ordinance banning discrimination against gays and lesbians. Opposition was swift and rancorous. The Rev. James Grove, pastor of a small Baptist church in the tiny hamlet of Loganville, invited Paul Cameron of the Family Research Institute to campaign against the ordinance. (The Southern Poverty Law Center’s website calls Cameron an “infamous anti-gay propagandist” who “churns out hate literature masquerading as legitimate science.”)

The ordinance eventually passed, but it was a bruising fight. In an article that appeared in the “York Daily Record” the following year, David Fleshler wrote, “Most gays and lesbians remain in the closet, fearing harassment and the deep-seated attitudes that new laws can’t change.”

That may sound discouraging, but it’s important to note that “Out in Central Pennsylvania” is largely a book about ordinary people and grassroots activism. Even when the authors discuss individuals whose actions take on a greater significance for the larger LGBTQ community within their region, like Jerry Brennan, who founded the Gay Switchboard of Harrisburg and Dignity/Central PA in 1975, or Jeanine Ruhsam, who started TransCentralPA in the late 2000s, they are not discussing figures with the name recognition of, say, the recently deceased activist Larry Kramer.

What the future holds for the LGBTQ residents of central Pennsylvanian remains to be seen. But as “Out in Central Pennsylvania” clearly shows, they can certainly be proud of their history.