Consider the question: what if the COVID-19 pandemic lasted for decades? That’s what Javontae Lee Williams, program coordinator for the Department of Public Health, asked those viewing an August 6 webinar on ending the HIV epidemic in Philly.

“Imagine COVID existing at the epidemic or pandemic proportions for 30 years. When you think of it in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, we have lived at this moment of crisis for a long while,” he said.

Williams said that due to advances in HIV treatment and delivery programs, the HIV services community has become complacent in terms of the status of the epidemic, even though we have the ability to end the epidemic with those advances.

In the presentation, Williams said that ending the local epidemic is contingent on addressing issues like HIV stigma, homophobia, the availability of resources, access to education, accessibility of care, gaps in information, as well as social factors such as poverty, inadequate housing, racism, deep-seated medical abuse that causes community distrust in public health entities, and historic police violence and incarceration.

He also acknowledged the impact of HIV on LGBTQ folks of multiple races, including Black and Brown people.

Williams walked the audience through Philly’s Ending the HIV Epidemic Plan (EHE), which is based on the federal government’s Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative. The EHE is divided into four pillars: diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and response.

He then discussed the public health department’s participation in planning activities and working with community partners, including the Office of HIV Planning, Penn Medicine, the Transgender Mobilization Project, and GALAEI.

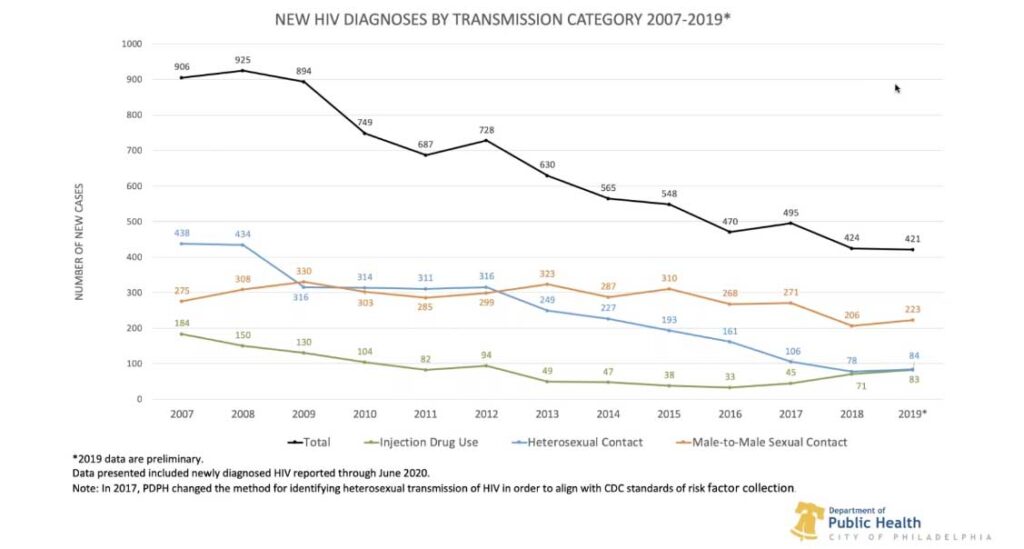

For the diagnosis pillar of Philly’s EHE, Williams illustrated the decline in HIV diagnoses through graphs. In 2018, for example, Philadelphia saw an overall decline in diagnoses, but not equally across all demographics. That year, 36% of new HIV diagnoses were among Black men who have sex with men (MSM), 71 newly diagnosed cases of HIV were among people who inject drugs who are also MSM, and one in four newly diagnosed HIV cases in 2018 were young people between the ages of 13-24.

“There’s still a lot of work to do among male to male sexual contact and also injection drug users, and heterosexual contact in transgender individuals,” Williams said.

Williams shared some methods of eliminating the HIV epidemic in Philly, such as bio-social screening, or making HIV testing accessible in medical spheres that offer chlamydia or gonorrhea testing, for example. He also discussed the need to expand upon community-based HIV testing and boost access to testing in community programs, which is happening in Center City but not necessarily in other areas of Philadelphia.

Williams added that organizations such as the AIDS Activities Coordinating Office (AACO) need to do better at reaching out to specific populations, including injection drug users, MSM, transgender people, and young people.

Regarding treatment of HIV-positive people, Williams highlighted the need for effective and widespread treatment. 87% of HIV-positive Philadelphians currently in care are virally suppressed. Having an undetectable viral load means a person is not able to transmit the virus. However, almost half the overall population of people living with HIV are not currently in care, and 40% of people living with the virus are not virally suppressed. Williams also said MSM of color are less likely to be virally suppressed than white MSM.

“We’re going to have to move our system from blaming individuals, and [start] taking personal responsibility,” Williams said in the presentation.

To address some of the barriers to care like provider accessibility and education deficits, Williams said that AACO is planning “to increase the capacity for immediate retroviral treatment,” up the ante in terms of keeping people engaged in HIV care, and develop “low-threshold, treatment-first models” where people who may be experiencing other issues, such as substance abuse, can receive HIV treatment first and foremost.

Under pillar three, prevention, Williams said that almost 14,000 HIV negative Philadelphians “should have access to PrEP, but only about 3,000 of them are actually accessing PrEP. That’s a huge gap.” He laid out strategies for increasing access to PrEP and other HIV prevention measures, including adding new models for PrEP, ramping up support for PrEP-related lab costs, creating networks of PrEP providers and connecting with peers and community partners to publicize the use of PrEP.

Regarding the ability to respond to HIV outbreaks, Williams discussed AACO’s DexIs project, which stands for demonstrating expanded interventional surveillance. The program serves to connect with newly diagnosed people who are willing to share how they navigated partially impenetrable HIV health systems, with a focus on Black and Brown MSM and trans women of color. The program also leads medical providers across the city to take part in a vigorous, de-identified review of new HIV diagnoses, and strives to hone in on missed opportunities and community resources via a monthly review.

Recommendations that have emerged from the DexIs project include providing guidance to health providers to facilitate regular follow-ups with patients after their initial appointment and start of PrEP and addressing detrimental provider language to avoid perpetuating HIV stigma. Williams also expressed the need to reassess the existing infrastructure of Philly’s HIV workforce to expose gaps, analyze quality of services, increase evidence-based interventions, and amplify sexual risk assessments.

He ended the presentation by promoting a “think outside the box” approach for ending the HIV epidemic in Philly, and he invited audience members to provide their feedback on the public health department’s EHE, which can be found at www.ehe.hivphilly.com.

“This is really about the community’s plan to end the epidemic,” Williams said. “We need your input, we need your voice.”