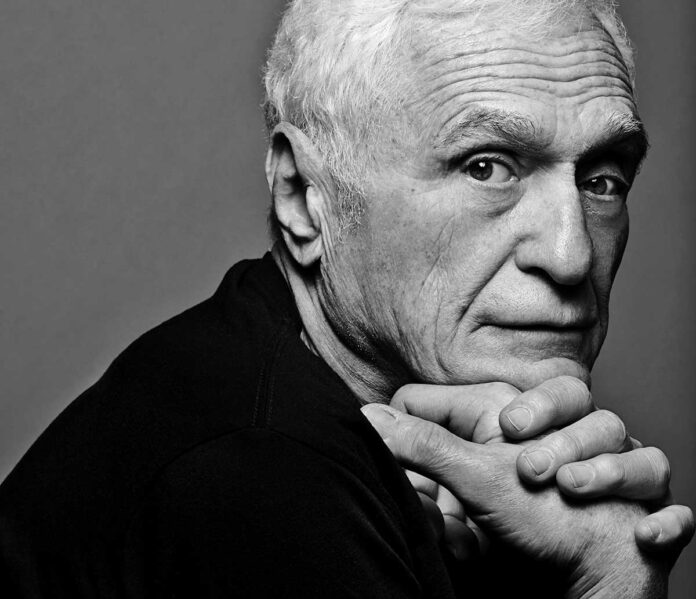

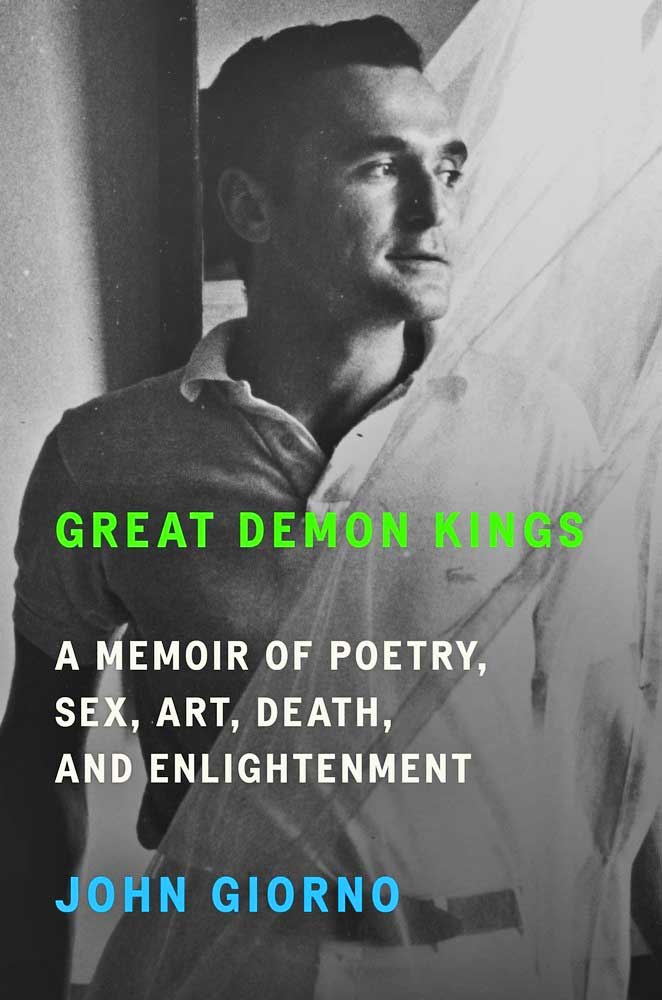

The late gay poet John Giorno’s posthumous memoir, “Great Demon Kings” is a deep dive into the New York poetry and art scene of the Sixties as told by one of its survivors. Giorno established a reputation as a poet in his own right, but it was his intense sexual relationships with artists Andy Warhol, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns — as well as writer William Burroughs and others — that allowed him entry into the hallowed world.

Giorno’s book focuses on three particular periods in his life. The approach reads more like a diary turned narrative than a proper memoir, but that is not a drawback. The author is immediately ingratiating when he describes doing a poetry assignment in his high school English class and seeing poet Dylan Thomas read. He is turned on to Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and the work of Jack Kerouac, meeting both at a party while in college at Columbia. He eventually meets Warhol (pre-Factory fame) and becomes his lover.

“Great Demon Kings” shows how Giorno became ensconced in the art world. Warhol would take him to happenings, and they would spend time together. Warhol also famously filmed Giorno for the 5-hour plus documentary, “Sleep,” which buoyed the poet’s celebrity for a while. For readers wanting dish on the pop artist, Giorno writes about sex with Warhol, who had a foot fetish.

Giorno often reports about the numerous hangovers he suffered and how he smoked weed at any and every opportunity. This is, of course, part of the Sixties milieu, and while it may have been great for the poet and his artistic friends, it gets a little tedious to read about how drunk and stoned he was.

More interesting are Giorno’s recollections of meeting Salvador Dali and the keen observations about the great surrealist’s late career. There is also a strange section involving Jane Bowles examining herself (and that’s a euphemism) in a mirror in Tangiers when Giorno was staying with Paul Bowles and Brion Gysin. And late in the book, he fondly recalls an explicit tryst in a men’s room with up-and-coming artist Keith Haring.

The author admires the artwork by many of his peers and lovers, but when Giorno talks candidly — as he does late in the book about his frenemy, Allen Ginsberg — his opinions are insightful, which is why readers might want to know more of what he really thinks.

Readers may also want more of Giorno’s poetry. The few samples of his work are fantastic, such as his seminal “Pornographic Poem.” There are a few discussions of his sound poems and his efforts to present poetry in a new way — for example, he worked with Robert Moog, of the synthesizer fame. Giorno also developed the wildly successful public poetry service, “Dial-A-Poem,” which randomly provided callers with work by Burroughs, Ginsberg, and others.

That Giorno’s poetry featured gay imagery in a time when many artists were reluctant to be out or include queer content in their work is critical and inspiring but underdeveloped.

“Great Demon Kings,” concentrates on Giorno’s interpersonal relationships, and a bulk of the book chronicles the step-and-repeat romances he had with Warhol, Rauschenberg, and Johns. The poet falls for the artist. They have great sex. Things are going along fine until something happens, and then it ends abruptly. Giorno looks back at the good and the bad in these affairs, and he acknowledges that he is a kind of whore with a heart of gold. He also discusses his depression.

But his relationship with William Burroughs is different and special. These two men did have sex (a really vivid passage) but developed a close bond that truly comes across in the text. There are extended scenes of Giorno and Burroughs sharing meals, living in the same apartment and a long discussion of Burroughs’s death and Giorno’s efforts to connect with him in the Bardo (the world between life and rebirth).

“Great Demon Kings” also emphasizes Giorno’s Buddhist practices and meditations, his visits to India, including one with Allen Ginsberg, meeting the Dali Lama (whom he gives a book of his gay poems to!), as well as his learning from various gurus. Giorno duly chronicles his enlightenment, though it is not very enlightening. In contrast, his impromptu trip to attend Woodstock captures an experience of that music festival with unerring detail.

One additional quibble: there are fabulous photos in the book, but they are all reproduced the size of about two postage stamps. Larger images would have been appreciated.

Giorno ends his memoir introducing Ugo Rondinone, an artist who became his lover, muse, partner (for 22 years) and eventual husband. It is gratifying, but also feels tacked on.

“Great Demon Kings” shows that Giorno’s heady journey of sex, drugs, art, celebrity, death and poetry was mostly worthwhile. His book, while flawed, is too.