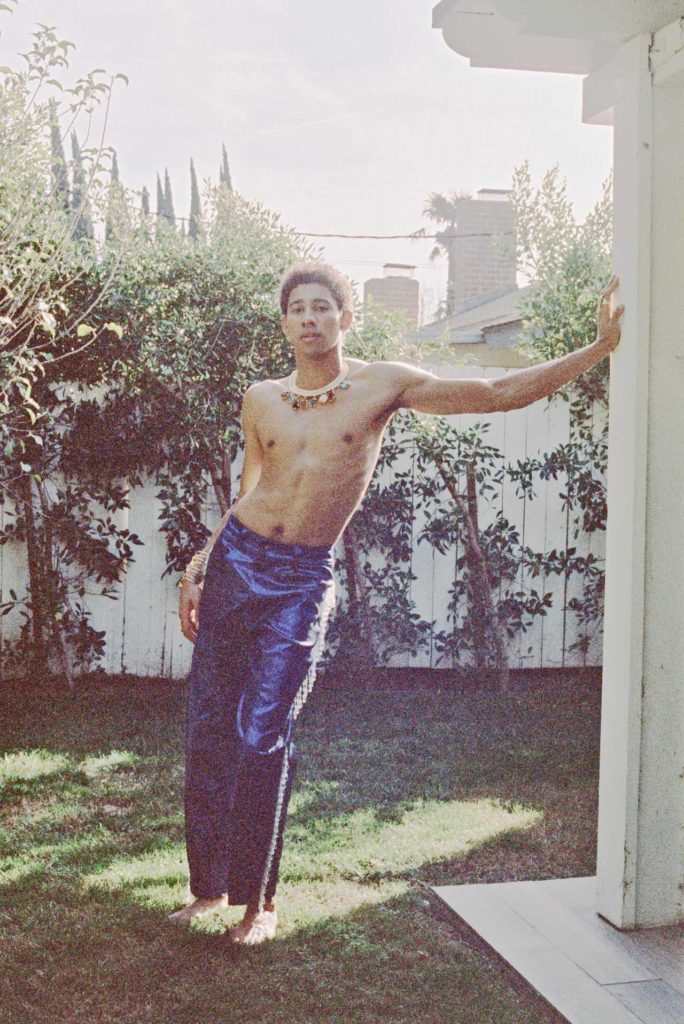

Once Keiynan Lonsdale made no apologies for who he is, the music followed suit. The star of the CW’s “The Flash” and 2018’s gay teen comedy “Love, Simon” celebrates his Black queer identity on his 14-track anthemic solo debut “Rainbow Boy.” Dance-pop song “Gay Street Fighter” is an audacious strut of a rally cry, proclaiming that even God is gay. And with a shout out to “my non-binary bitches,” “White Noise” and its buoyant groove lifts the stories of Black people that have fallen through the cracks.

Lonsdale’s album comes at the same time as “Love, Victor,” the “Love, Simon” spin-off on Hulu. In the series, the 28-year-old Aussie star reprises his role as quiet high-schooler Bram and becomes instrumental in Victor’s journey to authenticity.

When I recently connected with Lonsdale during a Zoom call, he was riding out the last two days of his mandatory 14-day quarantine in a hotel in Australia. At one point, the phone rang. And then it rang again. “Don’t mind me,” Lonsdale said, laughing. “I’m in the Australian quarantine right now, and so, actually, they call and check on you each day.”

In quarantine, Lonsdale has been able to “take stock of the album release, the state of the world…” He laughs again. “And the state of myself.”

When did you feel you could be unabashedly yourself in your music?

There was definitely one moment; it was three years exactly before I released it, where I had this realization that the best way for me to create would be to hold absolutely nothing back. I realized I was in control of the songs that I would write, and it would be a matter of what the writing led with, or staying in this sort of fear mindset that I had my whole life. And for good reason.

But it felt kind of like a spell was broken, and I was like, “I can say this shit, I can ‘sing’ this shit.” In fact, it’s what sparked me to realize that I could have my own unique voice. Before that I would say that I spent a lot of time trying to be like others, but always wanting to have the gall to be able to be my own (person). But I didn’t know what that meant. So it was nice to have that spell broken.

So then being able to mentor a younger gay person on “Love, Victor” and remind him that there’s no one way to be LGBTQ, what did that feel like for you?

It was great to be able to play a role that could share that knowledge, because it’s something that I think each of us have needed to hear at one time: that you are still the one that gets to define who you are. There is no one way, and as much as we like to paint people with the same brush, it’s just not how it works. So I think it sends an important message. I’m glad that’s the route they went with with the (lead) character.

Going back to the fear you said you felt when you were younger, before you came out: How much of that had to do with you being a Black queer person?

Yeah, it had a lot to do with that. I didn’t hear and I still don’t hear…[there’s] a lack of music that proclaims same-sex love. What’s ultimately needed is that it’s normalized; that hearing a guy sing about a guy or about a girl, they can become one in the same and not something that is conflicting or jarring or uncomfortable, or something that people have to avoid.

Photographer Mark Clennon, who has been sharing images of the Black Lives Matter protests and demonstrations across New York City, described sharing Black stories as “whimsical defiance” in a recent interview with Interview magazine. For you, what does it feel like to be sharing your perspective and story as a Black queer person during our current racial justice movement?

It’s both empowering and exhausting. I think a lot of Black people would likely feel this way too, because it’s a story we’ve lived with our entire lives. For a lot of us, we’ve expressed it for a while. You know, I wrote a whole album about my experience, and I wrote the album, like, two years ago. So, it’s coming out now and it’s amazing on one hand that people are listening in a different way than they were before. That provides me with a lot of hope on some days. On other days you just want to live your life. You want to be able to live your life without having to explain it all the time. And so I think that’s where it’s important to have the balance of doing the fight and also knowing, How do you heal at the same time? Take care of yourself? So, yeah. It’s hard to describe.

I’m assuming the song “White Noise” was written a couple of years ago too. During the song, you sing, “All the white noise that we just don’t need, you better move over.” What kind of significance does the song take on now in the midst of this uprising?

It has reminded me of the necessity of it. I was of the mind where I felt like maybe this song was too on the nose, but then, clearly not. There are a lot of people who don’t understand the importance of this, and I wanted to approach that song with a level of joy and invitation, to be able to point out an issue, pretty clear as day, yet to say that there’s a way forward. I suppose everyone has a different way of how they share their message, and with that song I wanted to kind of teach — and with the album, in general — through song and dance.

“Love, Victor” has been getting attention for its diversity, something many people thought “Love, Simon” lacked. What are your feelings on how the show and the movie handled representation?

I haven’t seen the show in its entirety yet, so I look forward to that. But that was definitely one thing I thought was exciting about this show. When anything is getting a spin-off, you get a little bit worried and you’re hoping that it’s done the right way. But I appreciated that it was taking a turn from the movie and moving forward, taking further steps.

In one way, I’m really proud of “Love, Simon” and how things were represented, but I’m not unaware of the fact that that was one step and that there are still many that need to be taken. As people also said, this is one specific telling of what it is for one kind of person to grow up gay in a fairly accepting environment, in a sort of privileged position. And those are conversations to be had. I’m glad that the movie was both celebrated yet also a topic of discussion about “How do we keep going?”

When you accepted your MTV Movie award for “Best Kiss” for “Love, Simon” in 2018, what was it like to get on stage as an out queer person and in a dress?

It was super weird because I had come out a few weeks after we’d filmed [“Love, Simon”], so I was out for only 12 months by the time the movie was out. Then I was doing all these interviews and speeches; it was really strange because I only just came out. I was kind of very much in my own experience trying to figure a lot of stuff out.

But you seemed to have known what you were doing when you got on that stage in that dress.

(Laughs) Yeah, well…I was just trying my best to listen to the spiritual aspect of it and that’s what allowed me the confidence to wear what I wanted.

How did you feel up there?

I felt amazing. I was really nervous. I didn’t know what I was going to say until I started walking up. It’s a surreal kind of experience. But I was over the moon, to be honest. It felt like a dream. And I felt really supported in that moment. And yeah, it was quite magical. I felt magical.

Did you see the crowd reactions? They were so into your speech.

I definitely heard them. It was really exhilarating.

I see how you affect a lot of LGBTQ youth, and to that end, I wondered what you think being out and playing Kid Flash has meant to both LGBTQ and people-of-color communities?

It’s meant a lot of things. Because at first it was met with a lot of celebration, but I was also met with thousands of racist comments online the day that it was announced. Same thing when I came out. To be met with such celebration but then also the opposite, it’s a funny juxtaposition. But I am proud. I’m happy that Kid Flash is a superhero and the message I know that a lot of kids have been getting is: They’ve got to watch me as a Black man play a superhero, and then they compare it with the fact that I’m an out queer Black man who plays a superhero. We weren’t taught you could do that back in the day. And so if that empowers kids to know they can be limitless, then that’s the best thing ever.

As editor of Q Syndicate, the LGBTQ wire service, Chris Azzopardi has interviewed a multitude of superstars, including Cher, Meryl Streep, Mariah Carey and Beyoncé. His work has also appeared in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, GQ and Billboard. Reach him via Twitter @chrisazzopardi.