“Bully. Coward. Victim. The Story of Roy Cohn,” airing June 18 on HBO, traverses some of the same territory as Matt Tyrnauer’s fantastic 2019 documentary, “Where’s My Roy Cohn?” This latest film, however, is distinguished by being directed by Ivy Meeropol, who is the granddaughter of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Cohn unapologetically sought the death penalty for the Rosenbergs for espionage.

Both films take a slightly different approach to chronicling the closeted power broker who never admitted he was a homosexual, or that he had contracted AIDS near the end of his life. They each recount Cohn’s career as a lawyer, which spanned decades, starting when he worked as Chief Counsel for Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s to helping Donald Trump in the 1980s. But Meeropol’s focus is on the impact of her grandparents’ unjust execution. As noble as that is, the filmmaker awkwardly shoehorns these discussions — which include interviews with her father, Michael — into the larger portrait of Cohn.

The new film could almost be retitled, “Roy Cohn: This Time It’s Personal,” given Meeropol’s agenda to take down this man who caused her family so much suffering. The title “Bully. Coward. Victim.” is generated from the words on Cohn’s square of the AIDS quilt. Meeropol and her father went to view the quilt and unexpectedly stumbled across Cohn’s square first. This film is most certainly not designed to humanize its subject.

Meeropol’s documentary is a bit of a patchwork in itself. She edits awkwardly between episodes, time periods and topics that create a general impression that most viewers no doubt already hold — that Roy Cohn was evil.

The filmmaker interviews Peter Manso, who interviewed Cohn for Playboy, and then flips back to a discussion of her grandparents. She has Cohn’s cousin, David Marcus, talk about a relative in Sing Sing, where the Rosenbergs were held, then cuts to “Angels in America” playwright Tony Kushner, who makes the not very insightful connection that he was interested in writing about Cohn because, like Kushner, he was Jewish and gay. New York Post columnist Cindy Adams talks about placing items in her articles for Cohn, whom she calls a friend, but later dishes about returning art he never paid for from a dealer she knew. There are also discussions of Cohn’s clients which range from mob bosses to Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager, the owners of the famed nightclub, Studio 54, where Cohn often partied. (Tyrnauer also made a great doc on the nightclub).

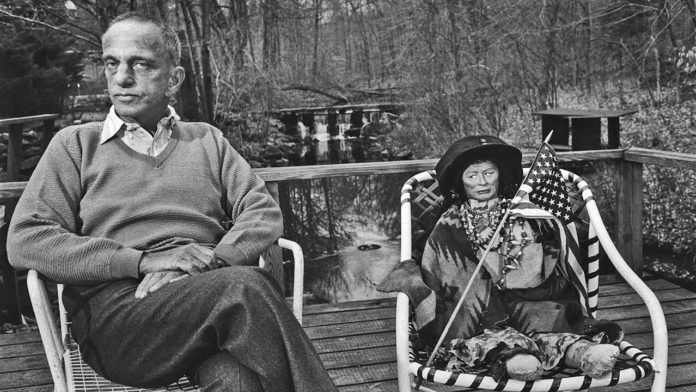

“Bully. Coward. Victim.” is lively when it presents Cohn’s questionable behavior. There are some intriguing reports that Cohn never “owned” anything (so he could avoid paying taxes) and left numerous unpaid bills. Meeropol’s scrutinizing of Cohn’s sexuality, features amusing anecdotes by John Waters about Cohn’s summering in Provincetown, as well as Ryan Landry’s account of being picked up and driven to a remote house to be Cohn’s companion. This story, however, does not require reenactments of driving through the woods or a shot of a fireplace to communicate the intimacy.

Arguably, the most interesting part of “Bully. Coward. Victim.” is the harassment charges Cohn brought against Richard Dupont in the early 1980s. Dupont went into business with Cohn to develop a gym, only for Cohn to stiff him. Dupont waged a campaign to embarrass Cohn by calling the police and fire departments when Cohn had guests over and publishing a magazine, “Now East,” with lascivious cartoons depicting Cohn in gay situations.

However, the impact of Cohn being disbarred — a situation that one interviewee claims was more devastating to him than his AIDS diagnosis — is practically glossed over. In contrast, clips of out actor Nathan Lane playing Cohn in “Angels in America” and having Lane talk about his impressions of Cohn seem superfluous. Likewise, interviews with Cohn’s Provincetown landlord, or a woman whose restaurant Cohn held court in, may be Meeropol’s clumsy attempt to flesh out her main (and obviously biased) goal of defending her family’s reputation.And to that end, there is a compelling bit featuring Michael Meeropol goading Cohn on TV to sue him if he is lying about Cohn knowingly doing what he did to the Rosenbergs. If only the filmmaker had focused on just this aspect of her story, her film might have been stronger. Of course, that would have made “Bully. Coward. Victim.” a 20-minute short.

Meeropol’s film never generates sufficient outrage about Cohn’s manipulation, and corruption, even if viewers are not aware of Cohn’s full history and abuse of power. Instead, this documentary just makes one wish this treatment of a fascinating if repellent subject was better.