Mark Horn marched in the first gay pride parade in New York in 1970. In pride parades since, he has often held the banner of Gay Liberation Front, the activist group born out of the Stonewall Riots. Horn’s journey through the gay rights movement, from GLF to Gay Activists Alliance to founding two university LGBT groups, has been as much a spiritual one as a political one. Like many gay people, he left organized religion when he was young, eventually finding his own blend of spirituality that includes parts of Judaism, Buddhism, Tarot, and Kabbalah, a form of Jewish mysticism.

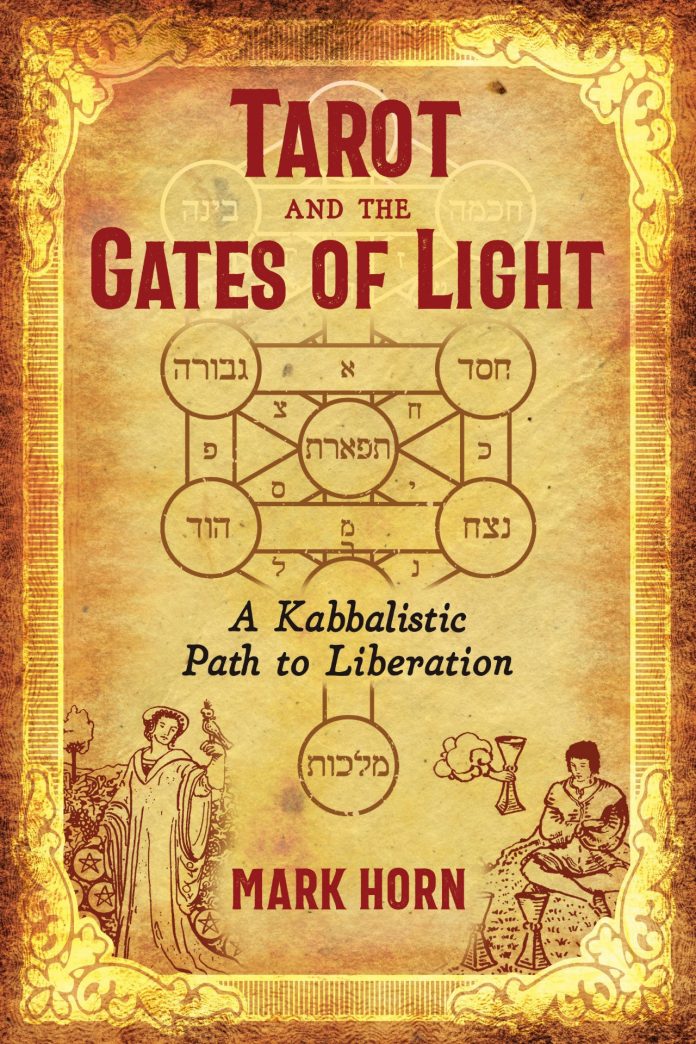

Horn’s new book, “Tarot and the Gates of Light,” is an exploration of Tarot, the cards commonly used in divination readings, and their relationship to Counting the Omer, a 49-day spiritual practice that commemorates the Jewish people’s exodus from Egypt to their receiving the Torah at Mount Sinai. Each day for seven weeks, the book guides people through Kabbalistic meditation and prayers using Tarot cards as a backdrop. Weaving in bits of his own life story as well as cultural references including Mel Brooks, Japanese pottery, and Broadway musicals, the book is a spiritual guide, memoir, and self-help text rolled into one.

PGN interviewed Horn about his book, his time in the gay rights movement, and how spirituality and the divine affect us all.

You were a member of Gay Liberation Front in the ‘70s. What was the spiritual pulse of that and other early activist groups? Were there many people who were religious?

Back in those days, GLF was busy freeing ourselves from all societal constraints. We weren’t interested in marriage equality. We felt marriage was a tool of the state, and a way that religion controlled our bodies so that many of us were anti-religious in all different ways. I don’t think there was anybody in GLF who was particularly in a faith community at that time.

Does the number of queer faith groups today in all religions surprise you?

One of the things I like about a number of faith traditions, Judaism among them, is that it’s non-dual. It believes sexuality and spirituality are not separate. This is at the root of the Catholic teaching. People believe you can’t do certain things because they’re not spiritual, but actually, no, it’s all in your attitude of how you approach it. Loving another man can be just as spiritual as loving a woman. There are different ways to connect with one’s spirituality. And as long as one is doing it from a position of integrity and rigorous self-honesty, then I think that it’s the way to go, whatever’s right for you.

How do you think LGBTQ people can use your book’s 49-day journey, which you describe as a “spiritual MRI,” to improve their lives?

The book is in some ways like any self-help book, except that it comes at it from the perspective of two mystical traditions — Kabbalah and Tarot — that give you a new vocabulary for a way of looking at the world. Those traditions allow people to open up things in themselves because it gives them a container that will feel safer to do so.

A lot of the questions in the book relate to our willingness to receive love. I think that applies especially to LGBT people, many of whom who were taught that they were not worthy of love. In a sense, does Kabbalah and Tarot allow for a person to see why they are closed off?

Once, a couple of years ago, I was reading for a young man I did not know at all. We were doing a reading, and readings often become very personal. I looked at one of his cards in relation to some other cards, and I turned to him and asked ‘Do you mind if I ask you a very personal question?’ He said he didn’t mind, that he’d come for the reading because there were things he needed to work out in his life. I said, ‘Well, I’m looking at this card, the nine of wands, and I’m wondering, are you in the closet?’ And he burst out into tears, because that’s exactly what his issue was. He didn’t know how to come out, he felt very defensive, and he felt that it was unsafe for him. Tarot cards are about exploring the dialectic dynamic between being open and being closed. Whether it’s in love, whether it’s in spirituality, whether it’s in our devotion to work, whether it’s in relationships with family, it’s all of these things. And the cards can help open us to seeing what our blockages are and how to free ourselves from them.

I think LGBT people, because we’re forced to question the nature of the world much sooner than heterosexual people, tend to look at life more incisively and read between the lines. We’re forced to question existing power structures and to find our own paths. I wonder if your sexuality is a reason that you’re so into Tarot and Kabbalah?

A couple years ago I started going to readers studio, which is an international Tarot conference, and I’d sort of noticed this in my time over life, but being in an international conference with Tarot readers from all over the world, I realized that I’d say 80 percent of the people at the conference were women, and the majority of the men were gay. On Facebook, there’s a Queer Men in Divination group with a whole bunch of Tarot queer people that I know now. Queer people have really always been a part of alternative spiritualties because we all felt spiritual exile from the traditions of our birth.

You use a lot of cultural references in the book, things like Freddy Krueger, Robin Hood, Broadway musicals. Is that a way of saying that all things have a spiritual element, or that you can find the spiritual in all things?

What I think is important to recognize is that the Kabbalistic view of the universe is that everything is an expression of the divine. It’s only our inability to see it that gets in the way. So part of this practice of counting the Omer is, when I say we’re clearing blockages, we’re also opening our eyes to better see the divine at work, not only in our own lives, but everything that’s around us. But also I include references from Broadway songs, Buddhist texts from the sutras, and Islamic poetry, and quotations from the Christian Bible, because I believe that in all of these spiritual paths — I would say Broadway musicals are a spiritual path — there is a way to find the divine.

The book is like four books in one. It’s a guide to self-betterment, it’s a book about Tarot, it’s a book about counting the Omer, and it’s also partly a memoir. Did you write the book knowing it would include so much stuff about you?

I realized that if I was going to show people how to do [this spiritual guide], I needed to show how I was doing it. And it also meant that I had to be open about some of the more difficult struggles that I’d faced. Part of doing this work is really facing your darkest things, your darker impulses, your complexes, and not being afraid to go there.

Did writing the book teach you anything about yourself?

One of the things about this book is that I’ve now come out on a larger stage, not just as a gay man, but also as a very serious Jew. It’s very interesting to me that this book came out this year, at a time when for the first time in my life since being a child, even in New York it feels unsafe to be Jewish again. I’ve actually started wearing a Kippah on the street, not even as a statement of spirituality, but also as a statement of political unity. I can pass as gentile, I can pass as a straight man, and I think it’s important for me to identify publicly as gay and as Jewish. My avatar on Facebook is the pink triangle yellow star, which queer Jews were made to wear in the concentration camps. I have the button I wear it on my coat every time I go out. I have a feeling most don’t understand what it means, but for me, it’s a way of saying I identify with these minority groups, and it’s my way of also saying, because I’m this minority I identify with the struggle of all minorities.

Another concept you explore in the book is the fact that religions borrow from each other and find self-affirmation in each other’s texts. It made me think of the question, do you think religions need each other to survive?

I don’t take the Bible literally, but I look at it as myth. Many people say ‘oh, that’s just a myth,’ but myth is a very important thing. A myth is a story that holds a deep truth that is very difficult to speak directly. It can only enter you through the mode of story. Part of the story in the Hebrew Bible is that there are 70 nations, and all of these nations have their own language and religion. The divine gave the Torah to the Jews and said you are a chosen people. Not “the” chosen people, “a” chosen people, chosen for a specific task. And we all believe that the divine is a jewel. Think of it as a diamond, and each religion has one facet and can reflect that specific facet of the light. But it’s not the entire light. Only when all religions come together, and we see the light in its entirety and appreciate the light coming from all of these traditions, will we ever really know god.

The book asks the reader to open themselves up, step by step, to intimacy and spirituality and acceptance, and it’s reminiscent to me of the coming out process. You have to gradually open yourself up little by little to accept yourself. Do you think the coming out process is similar to the book in a way?

When I first came back to Judaism as a gay man, I realized I was in two communities. In the Jewish community, I wanted people to know I was queer, and that that was part of my spirituality, and in the queer community, I wanted people to know that I was Jewish, and that was also an expression of my spirituality. And in both groups, there was a little suspicion of the other. Jews wondered if a person could be gay and Jewish, and the gay community said Judaism was a patriarchal religion and not good for me. I step outside all of that. I think that the process of coming out forces you to question a lot of things about yourself. As you said earlier, coming out forces you to question social structures, relationship structures, your own way of relating to other people, your own relationship to spirituality. One of the reasons you have all these gay men who read Tarot is because we’re closer to that intuitive sense and are able to connect to that realm because our categories are broken down more so we’re more open to receiving that information. I think that if one is open to that process in coming out, one actually opens up to a bigger heart for the entire world. However, one of the issues the queer community faces, is that because we’ve been so wounded by the traditions of our birth, we reject them, and we reject all kinds of spirituality, and we then try to fill that hole with other things. It’s because many [queer people] feel in spiritual exile that they just turn away from spirituality and fill that void with other things, whether its consumerism, circuit parties, crystal meth, compulsive sex, etcetera. And this is true of not necessarily queer people only. Every group has issues that drive them in that direction. Spirituality throws a great light on each of us. And when you throw a light, it also exposes the shadow. And you have to open up to that shadow so it doesn’t run you, so that you don’t fall prey to it. That’s also part of what this path is about. It’s opening up and looking at your shadow, so you can heal.

“Tarot and the Gates of Light” by Mark Horn is available now. For more information, visit http://www.innertraditions.com