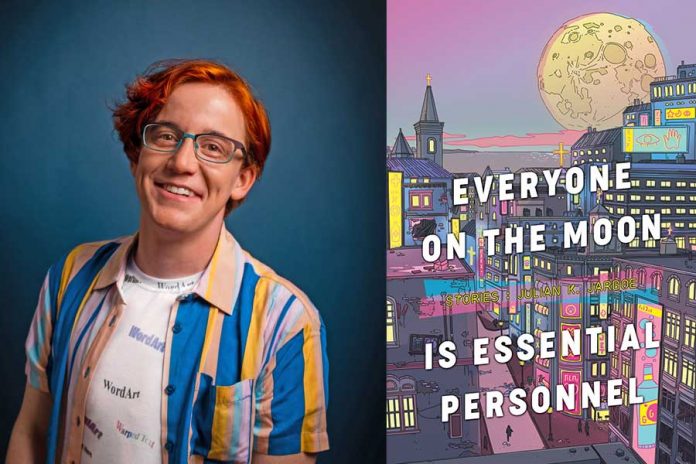

Trans author, writer and artist, Julian K. Jarboe casts a wide creative net with their debut collection of speculative fiction short stories, “Everyone on the Moon is Essential Personnel,” available March 1 from Lethe Press.

In Jarboe’s collection, 16 stories run the gamut — dystopian science fiction, body-horror fairy tales and blue-collar queer resistance that explore the themes of body dysmorphia, transformation, the realities of laboring under late capitalism and society’s faith in big tech.

PGN talked to Jarboe about the inspiration for their stories and how they fit into the changing social and literary landscape.

Did you have an idea of how all these stories would fit together when you were writing them?

I started off with a shorter collection originally. Some of them were deliberately planned to be conversations with each other from the get-go. What happened is the other stories that I originally thought would be in a smaller collection grew into resonance when I started revising some of the newest pieces in there, and I realized that it was linking back to both the original short collection as well as the other thing. It kind of grew and mutated into deliberately chosen stories that are meant to be next to each other for sure.

Science fiction and futurism always speak to or touch upon societal concerns. What do your science fiction stories tell us about the future of society?

This is a little bit cheeky but also deadly serious in the way that I know we’re joking, but I sometimes call the more science-fictiony stories in the collection mid-apocalyptic instead of post-apocalyptic. The future for me is always a concept that really only means anything about the present and the way people talk about the future. Of course, they’re always talking about the present and the past. People are going to come to different stories with different experiences, but I try to emphasize that a lot of the things that are being exaggerated in the near future in the stories are about right now for some people and the past for others. Typically elements about really terrible living conditions or really extreme environmental conditions, I didn’t intend for them to be warnings about what could come to pass. The most realism in there is about things that really happen to me and people that I know. There’s a lot of meta-conversation in there about the future, and there are science-fiction stories where the characters have science fiction in their lives also. I think that circular conversation about what we mean when we talk about the future and whose future is definitely a key point.

How do the fantasy and fairy tale oriented stories fit into the overall scope of this collection?

The fairy tales came out of an exploration of the first-person. Almost all of the stories are from the first-person point of view. There’s a neat thing with first-person. It’s deceptive. Some people think having the first person, the ‘I,’ being the narrator is more relatable because it’s like listening to someone talk to you. But the opposite is actually true. You don’t know if the person that is talking to you is giving you all the details. Everything is filtered through that perspective, and you’re actually getting a more deceptive, more evasive, flatter reality than you might get from a more omniscient narrator. So I wanted to do that on purpose with the way that fairy tales pose. It is what it is. If something is stated in a fairy tale you just assume that’s how the world works. I wanted to combine those two thoughts: to very deliberately work with worlds where rules are what they are and people are what they are in those worlds, and to ask the reader to trust the story, which is not to say they necessarily always have to sympathize. They won’t have all the information, and they have a picture of the world they might think they are getting, but they can go with the rules the story puts out and accept them.

Is this collection of stories specifically intended for an LGBTQ audience?

There’s definitely an appeal to audiences outside the LGBTQ community. My default reader is going to be that person, not because that’s the only person I want to talk to but because I sort of can’t help it. That’s the perspective that I bring. It’s a double-edged sword to claim that I’m writing for LGBTQ people because it would then create this inverse assumption that all LGBTQ people will find it relatable and that is not true. I think there are lots of people outside our community that have no relationship with queer themes in other works that will find things that will resonate with them. There’s a sensibility of surrealism and anger and intuition and knowledge that the body holds that I hope will resonate beyond one demographic or another.

With transgender issues and gender identity becoming a topic that is more frequently discussed in the mainstream press, do you think it will attract a broader audience to these stories?

I think it would in some ways. When I say these are trans stories by a trans writer, that’s true technically. If you are interested in reading works from a trans perspective, it’s impossible for me to remove that perspective from my work so you’re going to get it. One of the things exciting about right now is that there’s so much trans writing coming out that it need not be a monolith. So I don’t necessarily feel the pressure that I would have 5 or 10 years ago to speak for everyone or present on behalf of everyone to an outsider, and that is a huge relief. It means you get to win both sides of it. This is trans writing. Yep. Absolutely. It’s by and for trans people. And also you have people who are like ‘some of these stores aren’t about gender at all.’ Yes, there are other things going on in my life. I actually do think about other things. It’s nice to be part of something that is growing so much that it’s freeing for the writer and the reader to have other concerns and complexities.

“Everyone on the Moon is Essential” by Julian K. Jarboe is available March 1. For more information, visit http://juliankjarboe.com.