“Cunningham,” Alla Kovgan’s entrancing documentary about out gay choreographer Merce Cunningham, celebrates its subject by tracing his work over 30 years, from 1942 to 1972. (His career spanned 70 years). The film, which was shot in 3D, opens in 2D format today at the Landmark Ritz Five cinema.

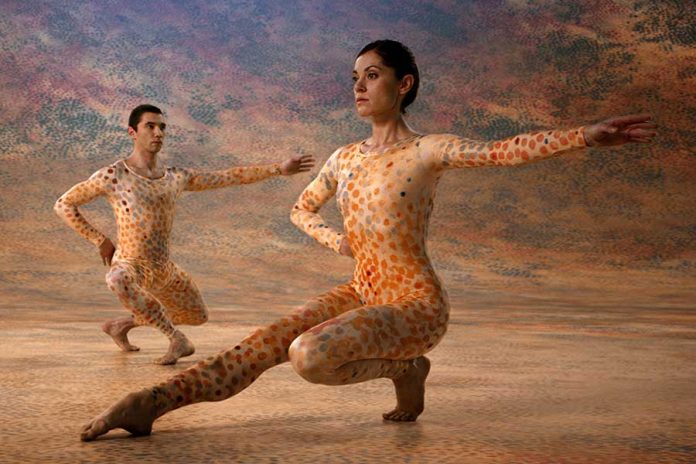

Fans of the dancer and choreographer will certainly swoon as Cunningham’s life and work are fabulously showcased. In many scenes, contemporary dancers recreate some of Cunningham’s famous pieces, including “Suite for Five” and “Crises,” among many others. The performances take place in all kinds of venues, from tunnels, to studios and theatre stages, as well as inside houses and even on rooftops — shot via helicopter from above. Kovgan appropriately films most of the dancing full-bodied rather than in close-up, which provides viewers with the opportunity to grasp the complexity of the choreography while also marveling at the beautiful bodies in motion.

“Cunningham,” however, may be less interesting to viewers who do not connect with the distinctive style of dance being performed. Throughout the film are discussions of negative reactions to Cunningham’s work. In Paris, some folks threw eggs and tomatoes. But Kovgan uses archival footage to let Cunningham explain his style — to the extent that he will. The choreographer rejects categorizing his dance as “modern” or “avant-garde,” calling it simply, “dance.” He wants the bodies and movement to be a pure form of visual expression. He took the grace of ballet in the legs and paired it with the “modern” dance torso to emphasize a kind of flexibility. It is the lithe bodies, bending and twisting, diving and shimmying, that make his work so remarkable. Moreover, Cunningham indicates that he wants to “present” dance, rather than provide some kind of “interpretation.” The film gets this point across clearly in its early scenes.

Kovgan also delves, perhaps too briefly, into Cunningham’s relationship with composer John Cage. The love letters the men exchanged and archival photos depicting their romance are wonderful.

In addition, “Cunningham” features interviews with members of the choreographer’s company. The last original member left in 1972, which is why the film ends that year. The dancers talk about how they worked with the choreographer, who explains he often trusted them and encouraged expression and eschewed having a structure or routine for his work. He often relied on the excitement of chance and acknowledged that sometimes it worked, and sometimes it didn’t. One of the most fascinating sequences in the documentary has Cunningham working with Sandra Neels and Gus Solomons, Jr. as they perform a fall while their bodies are intertwined.

Few moments offer a discussion in detail about the technique of the choreography. When “Suite for Five” is performed, Cunningham talks about using a stopwatch — anathema in the dance world! — to gauge the timing and movement. This also prompts a comment that detractors find Cunningham’s work “cold” and “inhuman.” But for many, the timing, beat and rhythm of this work is unique and exciting. His staging of “Antic Meet” had a dancer tie a chair onto his back, and the routine is recreated for the film.

One person attracted to Cunningham’s (and Cage’s) talents was the artist Robert Rauschenberg. He claims he connected more with these artists than he did with his fellow painters. Rauschenberg, who was bisexual if not gay, spent years collaborating with Cunningham and Cage, designing sets and costumes for several productions before he quit working with them in 1964.

The gay historical tidbits are interesting, but it is the performance scene where “Cunningham” really excels. It is not just that Kovgan stages each dance scene in a highly stylized fashion, but that the film dedicates sufficient screen time to the productions to allow viewers to get caught up in the performance. One of the best sequences in the film is “Rainforest,” which is staged with giant, floating, silver pillows — meant to resemble clouds — from Andy Warhol’s Factory. The dancers move between the pillows wearing flesh-colored bodysuits that have been ripped and torn — by out gay artist Jasper Johns (in the original).

Another highlight is the dazzling work “Winterbranch,” which is staged almost in darkness as various spotlights circle the dancers. The performance here is meant to suggest violence, but Cunningham leaves it up to viewers to ascribe specific meaning to the work.

In addition, the performance of “Second Hand” is also notable as dancers in bright costumes perform on a black, reflective stage in a riot of color and movement.

“Cunningham” is ultimately a feast for the eyes. It may prompt viewers to watch — or learn — more about Cunningham after the credits roll.