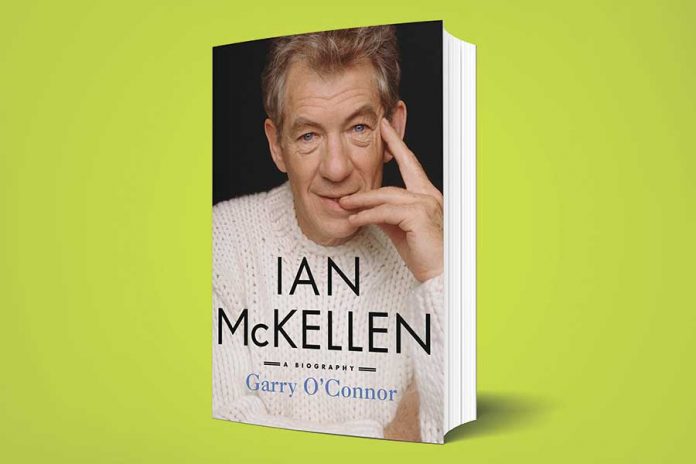

Garry O’Connor knows out gay actor and activist Sir Ian McKellen from their days attending Cambridge, back in 1958. However, while O’Connor’s friendship with McKellen might suggest he would be a fine biographer of the gay icon, the author’s new book, “Ian McKellen: A Biography,” is mostly a lazy hagiography. There are sloppy copyediting mistakes throughout and undocumented assertions. When O’Connor claims that “The Fellowship of the Ring” was voted, “The Greatest Movie of All Time,” he fails to include by whom.

O’Connor explains that McKellen does not want to write his memoir, nor does he want to “get involved with any book.” To that end, O’Connor hopes to “pluck out the heart of the Ian McKellen mystery” and explain the actor’s career, personal life and character. He does an only satisfactory job in that regard. O’Connor writes as if he is afraid to offend his friend. O’Connor provides banal insights, as when he reveals that making “Lord of the Rings” in New Zealand allowed McKellen to pursue “his favourite hobby, which was looking at countryside and especially mountains.”

“Ian McKellen: A Biography” briefly presents the actor’s childhood and family. His parents Denis and Margery raised McKellen in Wigan and Bolton. His mother, to whom he was close, died when he was young. His father remarried a woman named Gladys. He came out to Gladys but not to his father.

Many descriptions have McKellen discussing his sexuality publicly. He comes out on Radio 3 in response to Clause 28, which “made it illegal to promote homosexuality” and prompted his activism and support of gay charities and organizations. He attracted some controversy as gay filmmaker Derek Jarman questioned McKellen being knighted by a homophobic government. There was also McKellen’s theatrical provocation where he ripped out pages of the Bible, denouncing Leviticus as “dangerous pornography.” But the book largely steers clear of politics, save McKellen kissing Tony Blair.

Instead, O’Connor focuses on the intimate. The author identifies McKellen’s first gay kiss at age nine, his first erection — brought on by seeing gay film star Ivor Novello in “King’s Rhapsody” — and when McKellen lost his virginity at Cambridge, with Brian Taylor aka “Brodie.” These tidbits are certainly key in shaping McKellen’s gay identity. Still, these facts seem to be included, along with the lengthy discussion of McKellen’s stage nudity and “impressive genitalia” for their salacious nature.

O’Connor emphasizes his subject’s sexuality at every possible opportunity, which is not necessarily a bad thing for promoting a gay icon. The author chronicles McKellen’s multiple sexual partners, which included an affair with actor Gary Bond and being “stalked” by Rupert Everett. McKellen’s lengthy, complicated relationship with director Sean Matthias, 17 years his junior, is discussed as is his talked-about relationship with 22-year-old Nick Cuthell (McKellen was in his early 60s at the time). The sense that McKellen was not comfortable being alone or always needed an audience is mentioned, but that provides the only insight into his personal relationships.

Readers can deduce that McKellen can be a difficult partner on stage and off. O’Connor at least says as much in the discussion of his plays, where the self-serving McKellen could take over a production and become the star even if he was in a supporting role.

The author recounts almost every McKellen production and performance in meticulous detail as if to flesh out the content of his book. Readers’ eyes may glaze over at some of the minutiae. While it is important to know about McKellen’s breakthrough performance, where he put a gay spin on Aufidius in “Coriolanus” and his Edward II production, which featured a controversial gay kiss, a detailed analysis of his work in “’Tis Pity She’s a Whore” and “Doctor Faustus” border on boring. Better are the analyses of McKellen’s most famous roles in “Bent,” “Amadeus” and “Richard III,” which lead to his long-desired screen career, as well as celebrated productions of “Uncle Vanya” and “King Lear.”

When O’Connor contrasts McKellen’s work with fellow actors, such as Derek Jacobi, or Ian Holm, the biography does generate some interest as it shows how McKellen’s approach differs from his peers and why it is unique. Moreover, the rivalry between Jacobi and McKellen, culminating in playing lovers in ITV’s “Vicious,” is a useful throughline to show how two very similar out gay actors navigated different careers with varying success. The discussion of McKellen’s “bromance” with actor Patrick Stewart is also notable in this regard, much more than a tacky thread featuring McKellen’s goal to surpass Laurence Olivier’s performances and career.

O’Connor sums McKellen up best when he describes him as “mischievous and generous.” It is the best takeaway from this disappointing book.