For the first year of the AIDS crisis, 1981, nobody knew what to call the disease. ‘Gay cancer’ was a commonly used term, but medical professionals didn’t name it Acquired Immuno Deficiency Syndrome until over a year after the first media reports surfaced. The playwright Eve Ensler once said “Naming things, breaking through taboos and denial is the most dangerous, terrifying, and crucial work.” While AIDS remained nameless, while the government denied research funds and the homophobic Moral Majority spouted falsehoods, resources including the PGN tried to find the truth and share it with those affected. Here is a timeline of the AIDS articles published in PGN during the first year of the outbreak.

July 10th, 1981: The first story on AIDS appears in PGN, written by J.R. Guthrie. The disease is called “a rare and fatal form of cancer” with 41 known cases in New York and California. Physicians are unable to diagnose the illness, making it hard to track exactly how many people are affected.

Oct. 30th, 1981: A news blurb on Dr. Dennis McShane, a member of the American Association of Physicians for Human Rights, claiming there is no evidence of “gay cancer” and that any associations between gays and the illness are anecdotal, not pathological.

Dec. 25th, 1981: A report on three independent studies by the New England Journal of Medicine that reveal the disease leads to a breakdown of the body’s lymphocytes (white blood cells). One possible correlation between patients studied is the use of nitrites, otherwise known as “poppers,” but there remains no explanation for why the illness affects primarily gay men.

April 2nd, 1982: A news brief on an article in the Wall Street Journal that reports the disease has been found in nine women and 23 heterosexual men.

May 14th, 1982: A follow up on the “poppers controversy” which states that some activists do not want nitrites banned because “far worse” substances would become popular, while some San Francisco physicians want more stringent regulation on nitrites.

May 28th, 1982: An article on a Philadelphia study conducted by the Center for Disease Control. Dr. John Hanrahan interviewed people with Kaposi’s sarcoma and pneumocystis pneumonia as well as a control group. His findings conclude that the men with the diseases had a greater amount of sexual activity and drug use compared to the control group.

June 25th, 1982: An editorial titled “The epidemic continues” which lambasts mainstream media for continuing to use phrases such as “gay plague.” The Philadelphia Inquirer is called out for headlines including “Gay Plague has instilled fear of the unknown,” and NBC is praised for its coverage on “Today.”

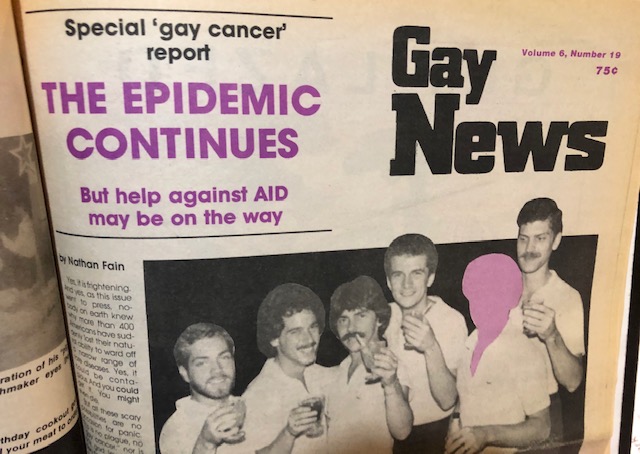

July 9th, 1982: One year after the first media reports, PGN publishes a front page, 4000-word special report on AIDS, written by Nathan Fain. The report provides both the latest medical information (including a debunking of the “poppers controversy”), as well as an analysis of mainstream press coverage.

By the time PGN ran the special report, much was suspected about the causes of the disease, though none of it was concrete. Even the name of the illness was still undecided. The CDC had begun using AIDS, but other names including AID (acquired immune deficiency), GRID (gay-related immune deficiency), CAID (community-acquired immune deficiency), and ACID (acquired immune-deficiency) were also used, not to mention the metaphors like “gay plague” put forth by both mainstream media and anti-gay conservatives.

Many experts quoted in PGN had hunches that sexual activity and intravenous drug use could be possible transmission routes. But those facts were unverified, and other guesses for what caused the disease, including poppers and fisting, were still being posited. There were no hard truths to come by. And even though reports confirmed that AIDS had also been contracted by heterosexual men, women, and children, it still became known as a gay man’s disease.

Nobody knew for certain that AIDS was a virus, or that it had found its way to the U.S. as early as 1969. Nobody knew in 1981 that 42-thousand people were already living with HIV and that number would more than double in one year. Nobody knew the extent to which the fearful would go to avoid the infected at all costs, the extent to which the homophobic would use AIDS as a vehicle to tell gay people they deserve to die.

For that first year the disease was a shifting puzzle, without a shape and with very few pieces to put in place. After the special report, articles on AIDS appeared regularly in PGN, both on the disease itself and the homophobic backlash that it spurred. Some weeks 75 percent of the paper’s news stories were about the epidemic. The reports and editorials in PGN, urging people to remain hopeful while also alerting them to the interference of politics and religion, shed light on an uncertain time for many. That work continues today.