Chet Catherine Pancake lives with their partner and child at Black Oak House — also the art gallery Pancake curates. The quaint but roomy West Philadelphia row home is across the street from Malcolm X Park and often adorned with drawings from Pancake’s daughter.

Pancake moved from rural West Virginia to Baltimore, Maryland, when they were a teenager and immersed themself in various art scenes. They built community that uplifted women, people of color and queer voices in music, visual art and performance. “In 1999 I said: no more white guys,” Pancake ruminated.

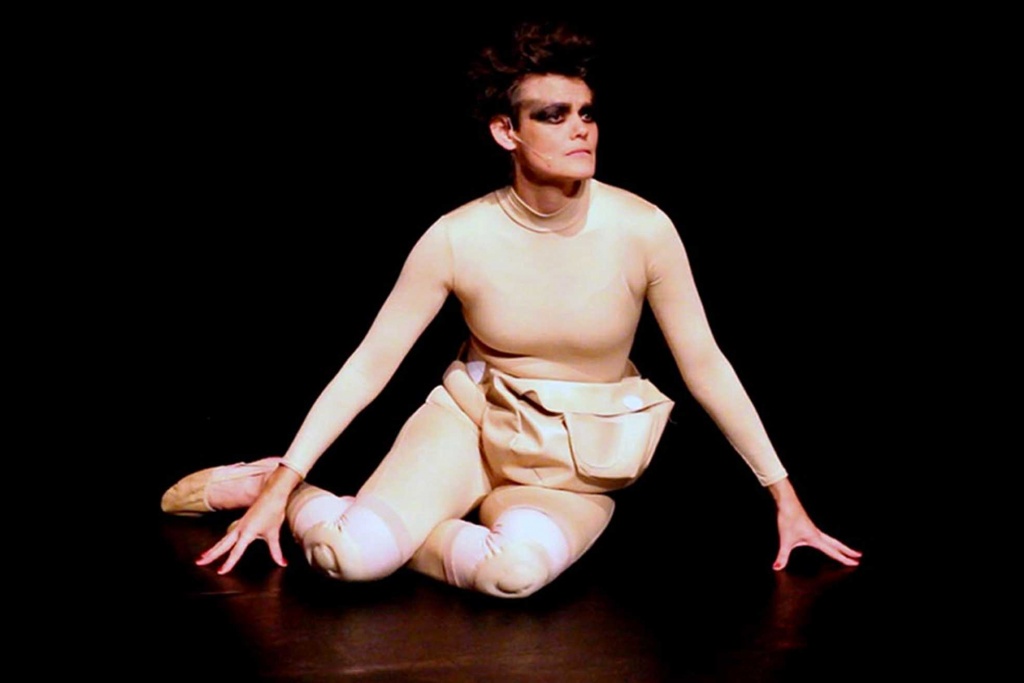

After moving to Philadelphia, Pancake found another well of artists with whom to form community — those genius inventors who were creating and preserving queer art. Enter “Queer Genius,” a film that explores the visionary work of Barbara Hamer, Black Quantum Futurism, Jibz Cameron and Eileen Myles. Billed as “a cinematic exploration of four visionary queer artists breaking down barriers in their creative fields as they confront fame, failure, censorship, family, gender and sexuality,” “Queer Genius” captures artists in their element, like capturing a dream. PGN talked with Chet Pancake about the film, as well as art, community, futurity and genius.

Your film explores the history of queer art and literature by way of Eileen Myles and Barbara Hammer specifically. How important is preserving and documenting history to you?

As a younger queer artist arriving in Baltimore, Maryland in the ‘90s out of the Appalachian mountains where many queer people were pulling up stakes and moving to cities in search of jobs and a new way of life, I was deeply influenced by books, movies and music that spoke to a new way of cultural life. I was essentially mentored by these complex artworks in a world that felt pretty extremely alienating. I saw Hammer’s “Nitrate Kisses” around this time, along with films like “Step Across the Border” and “W.R.: Mysteries of the Organism” that presented deep dives into intriguing alternate cultural ideas. I was also surrounded by a number of Baltimore artists — Laure Drogoul, Blaster Al Ackerman, Neil Feather — who kept alternative archives of their lives and worked largely outside the mainstream art world, and that resonated with me. I would consider alternative culture and queer culture my social/emotional/intellectual context, and I do think it’s very important to honor and document one’s “family” of choice — as well as biological family if you have one — regardless of the dominant culture’s acknowledgment.

Queer timelines seem altered, different than normative timelines — more fluid. How do you see your art, generationally?

This is one of the key motivators of my interest in “Queer Genius” and also Barbara Hammer and Eileen Myles. When I turned 40, I assessed my life and determined that I needed to make my creative life central to all my endeavors. I accepted that this may mean less economic success for me, which was very hard to do as I’ve never had financial support from family or external benefactors. I then became deeply curious about what it means to make queer art into one’s later years, and to me, it seemed a life choice that came with a sort of dignity that was not the case in the corporate world where I had been working for about 11 years. I actually see myself as more and more childlike, curious and hopeful as I get older, which has been a big surprise.

When I was younger, I was much, much more cynical, ironic, and “hard.” I was also much more identified as female then and endured very intense street harassment for years as well as all the other things that come with appearing in the range of desirable for cis straight men. My “softness” may also be due to caring for a child and also my embracing of my trans-masculine identity, which feels much more peaceful to my body. I found that Barbara and Eileen were much more in the present, working and active than almost any artists I know. It was extremely gratifying to document and learn from them. Also, Barbara, in particular, has been in and out of favor in the art world, so looking at someone’s history in terms of working through obscurity to fame back to obscurity and back to fame, etc., is an ocean that I think many “successful” artists swim in. I don’t feel in between generations, but I do feel over time, the urgent pressure to more intensely address constantly unlearning racism and the gap between pushing very hard to be inclusive over the years or devoting lots of time to it and the awkwardness of being asked to step aside when others need a certain space. I recognize in myself the “good feeling” of fighting for equality and then the stress of being decentralized or not “the diversity hero” when that is achieved. It’s a thing about white privilege on the left that is not talked about that much and should be more explored openly with empathy. The Leeway Foundation has taught me a lot about this process.

Do you feel most fulfilled as a curator or artist?

I feel equally fulfilled by both, but I work most currently as an artist and less as a curator. “Queer Genius” is a synthesis of both, and I think a sort of capstone of 15 years of volunteer curating and DIY organizing to create and diversify independent art spaces.

What moments were the saddest, most awkward and empowering during the making of “Queer Genius”?

Great question. The saddest A: Losing Barbara Hammer from this world as a living active force. I’m still sorting out my complicated grief. The saddest B: The utter lack of interest from the larger art world institutions in terms of funding or supporting this film in Philadelphia besides The Leeway Foundation, Bree Pickering, Kate Kraczon and Amanda Sroka.

The most awkward moments of the film were working with so many amazing musicians, cinematographers and people on the film and having to leave some of those folks’ work out in the final edit, i.e., getting people excited for the film, and then not being able to include commissioned music, visuals or ideas brought to me with total enthusiasm and generosity. I found the Kickstarter process and finding so much grassroots support for the film to be very heartening and exciting. Also, bringing my 7-year-old gender-expansive child to the Castro Theater in San Francisco for the premiere, and having her see the film on the big screen and seeing her name at the end in the dedication. She sacrificed a lot of time with me as I worked on the film, and it was very hard to endure for both of us. I basically worked on the film every single day for months, and she wasn’t sure why. Then she understood it was a “real movie,” and she was super psyched.

The film has quite a few tonal shifts, the kind of reserved playful madness of Hammer, the irreverent chaos of Jibz Cameron, rugged lifestylism of Myles and the intense, truth-to-power melancholia of Black Quantum Futurism. Did these tonal shifts influence your vision for the film or was it the result of editing, interviewing and process?

Yes … However, I am now pondering the melancholia of Black Quantum Futurism. Frequently they are described by white critics as “angry,” and I disagree with that, but it is a deeper and very rich range of abjection at times. Within this abjection and melancholia are also the frequent tender moments of care that they extend to each other and the community, so complex and very radical.

I originally was trying to impose a tone on the film by using expert testimony from a lot of art world big-wigs. This was a more analytical approach. However, frankly, Barbara Hammer rejected this tone and approach, and I think, in the end, she was right. I then worked with an editorial consultant, Fiona Otway, who helped me find the core tone in each portrait and also the story arc toward each artist’s personal genius and expression of that. I had asked each one specifically about “genius” in our core interviews, so that was then easy to build around that core concept.

What’s next for Chet Catherine Pancake?

I am currently [working] on a short fictional film in West Virginia addressing family dynamics and addiction as another aspect of my “Bloodland” fine artwork series. I’m also working on a larger video installation regarding the emotional and somatic resonances of ecological activism, landscape and labor around fossil fuel extraction on the East Coast of the United States.

The next showing for “Queer Genius” will be in Baltimore, MD, Nov. 21. For more information, visit facebook.com/queergenius.