There was a time when one out of every two Americans Gallup polled knew Alfred Kinsey’s name, and to gay men, lesbians and bisexuals, he was a living hero. Sadly, for the last quarter-century or so, calling Alfred Kinsey “the man who made the homosexual movement possible” has come not from that movement but the antigay industry.

On June 27, the late bisexual Indiana University zoology professor’s name was finally immortalized where it should have been long ago — in New York’s Stonewall Inn. His name now joins Harvey Milk, Edie Windsor, José Sarria, Christine Jorgensen, Bayard Rustin and others among the 50 individuals on the permanent National LGBTQ Wall of Honor “Honoring Pioneers, Trailblazers, and Heroes” who “contributed to the advancement of the LGBTQ community in a substantive way.”

Kinsey’s role is traceable to the birth of the gay rights movement in the United States after the first effort by Henry Gerber and his Society for Human Rights was smothered by authorities in Chicago in 1925.

As Lambda Legal luminary Tom Stoddard once told the Washington Post, “Civil rights shouldn’t be a matter of numbers, but they are.” Ours started with Kinsey’s 1948 “Sexual Behavior in Human Males” based on interviews with 5,300 men that shot to the top of The New York Times bestseller list.

Next to Kinsey on the wall is the late Harry Hay, who’d long dreamed of an organization of gays. Hay gave Kinsey and his book credit for mobilizing him in 1948.

“It was a shocker for us because we had assumed that we were a few hundred in every city. Turned out, we were thousands in every city that even he knew about. So, with my copy of [the book] under one arm, a sheaf of papers under the other, I go through the entire gay community as I know it at that time — which isn’t much,” said Hay.

Also shocking was how many Kinsey convinced to confide in him when a single sex act with another man could, then, lead to prison from one year in several states to life in Connecticut, Georgia and Nevada.

Kinsey thought it impossible to identify who was “homosexual” or “heterosexual.” It was only possible to identify and tabulate numbers of psychological reactions and overt behaviors. But the implication of higher numbers spoke for itself. According to Kinsey team member Wardell Pomeroy, after one interviewee realized how many experiences with men he’d acknowledged, “he rushed to the bathroom to vomit.” His profession? Psychiatrist.

Vocalist and comedienne Martha Raye’s satirical “Ooh, Dr. Kinsey!” was banned on the radio, which only triggered sales, allegedly 500,000 copies in three months.

Now if he’s timid around the girls

But around the boys he’s so sporty

His history is no mystery

It’s on page two hundred and forty

No wonder Bill was always strange

And kissed me with such poise

When I asked him where he’d been, he’d say:

‘Oh, out with the boys.’

A pioneer in nonbinary documentation, Kinsey wrote: “About 13 percent of the high school [educated] level has admitted such experience [with orgasm] after marriage and between the ages of 21 and 25. Only 3 percent of the married males of college level have admitted homosexual experience after marriage — mostly between the ages of 31 and 35. Younger, unmarried males have regularly given us some record of sexual contacts with older, married males.”

Hay, still married himself, hosted several gatherings ostensibly to discuss the book everyone was talking about but actually to promote his ideas for organizing; finding little interest, even mockery and hostility, until November 1950 when he and four others founded the Mattachine Society, the first enduring gay rights group in the United States.

Meanwhile, Kinsey had begun publicly advocating for the repeal of laws against consensual sodomy in 1949.

A 1950 syndicated newspaper article about what we now call the Lavender Scare read: “SENATE UNIT ADVISED TO READ KINSEY. If Dr. Kinsey’s sex data apply, there are 192 in Congress and half million in civil service who are ‘bad security risks.’ The Senate subcommittee investigating employment of ‘homosexuals and other moral perverts’ by the Federal Government had better read the Kinsey report before it goes very far.”

Unintentionally, Kinsey’s numbers only fanned the flames of politicized paranoia. To such witch-hunters, more homosexuals only meant more Communists betraying their country. Kinsey, himself, was accused of weakening America by reporting on any kind of sex outside the married, reproductive “norm.” One headline screamed: “Kinseyism Aids Reds.”

In 1952 and 1953, Mattachine applied Kinsey statistics in the cover letter to the first-ever gay questionnaire sent to political candidates — “there are at least 150,000 such persons in the Los Angeles area alone” — which was, in turn, quoted in an article in the Los Angeles Mirror.

Kinsey agreed to become an informal adviser to Mattachine in 1953 after they decided to help him find interview subjects for his next planned book, “Sex and the law.”

That fall his “Sexual Behavior in the Human Female” appeared, exploding hallowed myths about women’s sex lives, too. It was equated with an atomic bomb explosion and banned in South Africa, the Philippines, and on American military bases and ships. Some parents threatened to keep their daughters from attending IU and calls for his firing increased — all uncompromisingly and eloquently rebutted by university president Herman Wells.

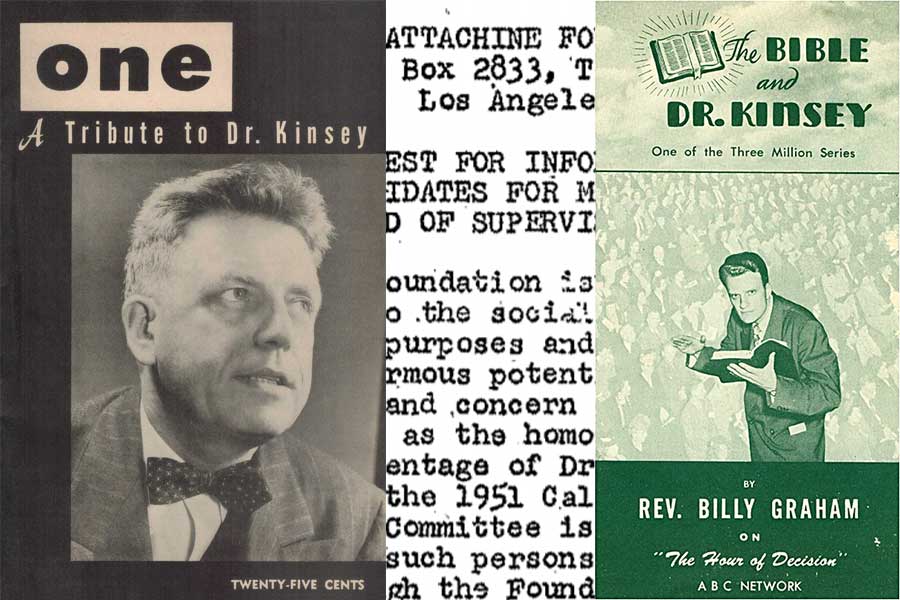

Rev. Franklin Graham’s Big Daddy, Rev. Billy, the first superstar evangelist, slyly called Kinsey and his fellow researchers “secret agents,” and raged in a radio broadcast, in print and to tens of thousands in revival meetings across the country that Kinsey was insulting women and teaching “our young people moral perversions that they’d never even heard of before.”

Mattachine gave Kinsey its 1954 Award of Merit, “For active promotion of individual freedom and education in the human community.”

In October 1955, Kinsey met with members of the Wolfenden Committee in London in support of decriminalizing sodomy in Britain. “Kinsey’s star status thus ensured that his views would carry weight,” said Brian Lewis author of “Wolfenden’s Witnesses: Homosexuality in Postwar Britain.”

They asked Kinsey about the “flood gate” argument that decriminalization would lead to an increase in homosexuality and the “Rake’s Progress” argument that it would result in more homosexual adults pursuing sex with minors. Kinsey told them that decriminalization (or less enforcement) in other countries and his study of over 6,000 males with homosexual experiences demonstrated there was no reason to believe such fears.

He added, “We have never seen a person [with predominately homosexual experiences who has] been affected by penal punishment or clinical treatment to further development of an exclusively or primarily heterosexual pattern.”

Biographer Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy said, “The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code of 1955 [which included recommending decriminalization] is virtually a Kinsey document. He was cited six times in twelve pages.” Kinsey met at length with the Illinois Commission on Sex Offenders, who told the legislature that “the Kinsey findings … permeate all present thinking on the subject,” and in 1961, the state became the first to repeal its sodomy law.

In May 1956, Kinsey visited the Los Angeles office of ONE magazine, the first successful gay periodical in the United States. He had been its first subscriber outside of LA, and in its first year alone, articles mentioned Kinsey in seven of its 12 issues. According to ONE historian Craig Loftin in “Masked Voices: Gay Men and Lesbians in Cold War America,” its staff was “deeply influenced by Alfred Kinsey’s famous two reports [and] his radical view that homosexuality was merely a benign variation of human sexuality and not some horrible genetic mistake. ONE repeatedly venerated Kinsey as a saint of gay freedom.”

In July 1956, “very much upset and agitated,” U.S. Senator Gordon Allott, a Republican from Colorado, forwarded to the FBI a pamphlet Mattachine had sent him. It, too, quoted Kinsey.

A month later, the movement’s saint was dead at only 62.

Exhausted — he had personally interviewed nearly 8,000 people one-on-one; desperately suing the federal government to stop their burning erotica he’d tried to import for research, and demoralized to the bone after funding was withdrawn by the Rockefeller Foundation panicked by a Republican-driven Congressional investigation into “Communist influence.”

Some closest to him believed he died mostly of a broken heart.

Behind his picture on the cover of the magazine’s August – September 1956 issue, a memorial editorial said: “To the staff and readers of ONE, his death is an immeasurable loss, deeply and personally felt.”

That month’s issue of Mattachine Review read: “It goes without saying that Mattachine and all its members and friends have lost a valued counselor and adviser with Dr. Kinsey’s passing. His helpfulness to Mattachine leaders will never be forgotten.”

The first issue that October of The Ladder, the magazine of the Daughters of Bilitis, the first American lesbian rights organization, quoted endocrinologist Dr. Harry Benjamin whom Kinsey had inspired to devote his practice to transgender people. “The world has lost an outstanding scientist and a champion of human freedom and happiness.”

Lesbian novelist Valerie Taylor in the May 1961 Mattachine Review said, “Probably the reams of material written in passionate defense of the homophile have done less to further the cause of tolerance than Kinsey’s single, detached statement that 37 percent of men and [13] percent of women who he interviewed admitted having [had at least one same-sex experience to orgasm].”

That January, fellow Wall honoree Frank Kameny applied various Kinsey statistics in his unprecedented Supreme Court challenge to his 1957 firing by the Army Map Service for being gay, his blackballing by the Civil Service Commission and President Dwight Eisenhower’s 1953 Executive Order banning gay federal employees.

Given Kinsey found that 13 percent of the men interviewed had more homosexual than heterosexual experiences for at least three years between the ages of 16 and 55, Frank wrote: “In the present Federal service, with its more than 2,000,000 employees, there are thus potentially some 260,000 persons intimately affected by these regulations and 600,000 against whom these regulations could be invoked.” In closing, he wrote, “In the name of justice … against infamous, tyrannical, immoral, and odious action of his government; in the interest of the public at large and of the nation as a whole; and in the particular interest of a large minority of the citizenry, this petition for a writ of certiorari should be granted.”

The Court refused, and, so, Kameny began a lifetime dedicated to lobbying every branch of government for gay equality. In his 1961 letter to President John F. Kennedy he spoke of the “situation involving at least 15,000,000 Americans”; to President Lyndon B. Johnson of “fifteen million homosexual American citizens.” To their successors and myriad other government officials, and in countless interviews and speaking engagements for decades, Kameny repeatedly used Kinsey’s research to prove that we matter.

Starting in 1965, he and his compatriots in the independent Mattachine Society of Washington echoed Kinsey numbers on protest signs in the first gay group pickets at the White House, the Civil Service Commission, Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, the State Department, and the Pentagon: “Fifteen million U.S. homosexuals protest federal treatment,” “Quarter million homosexual federal employees protest civil service commission policy,” “Quarter million homosexual American service men and women protest Armed Services policies,” “65,000 homosexual sailors demand new Navy policy.”

Hay’s and Kameny’s passion for fighting for justice sprang from the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, but it was Kinsey who gave them and others the ammunition — along with a belief in themselves they’d never had before. Late gay novelist Samuel Steward, who became close to Kinsey, called him “Doctor Prometheus,” saying, “He truly brought fire and light to the world. We looked upon him as a savior. He was the liberator. He was our Stonewall.”

His effect was never better dramatized than in the 2004 Kinsey biopic.

Without Kinsey would a Mattachine have formed; would Kameny have demanded equality; would the Stonewall riots have happened? No doubt, yes. But I also don’t doubt that without Kinsey, they wouldn’t have happened when they did. That’s why his name must be permanently displayed at Stonewall — to be visited and honored by new generations.

For however much researchers still argue about how many homosexuals you can get on the head of pin, by 1969 Kinsey’s once shocking revelation that we are many and everywhere had become common wisdom, weaponized again and again in the battles for workplace protections, against the military ban on LGBs, and for marriage equality.

Loftin said, “With Kinsey gone, others had to pick up his torch of sexual tolerance and spread the flame. Thousands and millions of gay people in subsequent years and decades preserved Kinsey’s spirit by asserting their right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and by fostering a more enlightened, tolerant and tolerable society to live in. Years later, we can be reassured that Kinsey’s humane message has not been drowned out by the fear-driven cacophony of intolerance, bigotry, and scapegoating that so routinely surges through U.S. politics and culture.”

Credit for the first contemporary effort to restore his place in history goes to Chicago’s outdoor museum of LGBT history, the Legacy Walk, which unveiled this memorial to him in 2012.