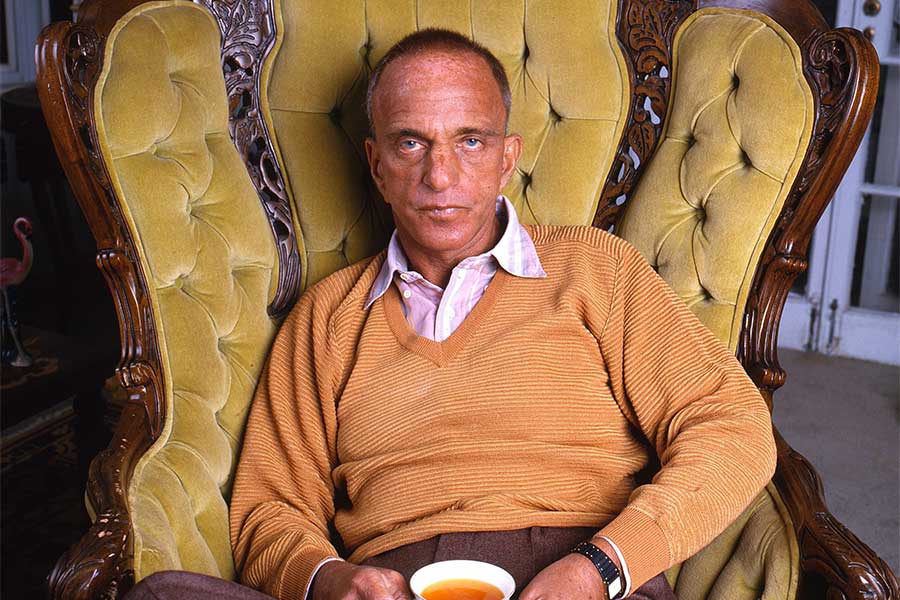

History shows how evil Roy Cohn really was. Described as “flamboyant” and “ruthless,” Cohn was a lawyer who helped send Julius and Ethel Rosenberg to their deaths; made a name for himself as Chief Counsel for Senator Joseph McCarthy; defended mafia kingpins, and had a protégé in Donald Trump. He even lost the Lionel train empire after taking it over. He never admitted he was a homosexual or that he had contracted AIDS.

Matt Tyrnauer’s detailed and layered documentary, “Where’s My Roy Cohn” — that titular quote is Trump’s — deep dives into the life and times of the singularly hateful man. He was a “political puppeteer,” pulling strings and manipulating the system to his advantage. He loved power and wielding it. The film opens Oct. 4 at the Landmark Ritz Five.

Tyrnauer elegantly traces Cohn’s rise and downfall decade-by-decade, showing how he was involved at key turning points in history. Cohn made his career on the backs of the Rosenbergs and urged Judge Irving Kaufman to pursue the death penalty in their case. Cohn then worked with J. Edgar Hoover at the FBI who recommended him to be Chief Counsel for Joseph McCarthy and his anti-Communist hearings. He investigated homosexuals as part of this work. Queerly, Cohn developed an affection for G. David Schine, who worked on McCarthy’s team. When Schine was drafted, Cohn tried to manipulate the system so Schine would be excused from duty. His efforts begat the Army-McCarthy hearings, and Tyrnauer features footage of the hearings, with discussions of “pixies” and “fairies,” that belie the subtext of what was really on trial. It also led to the Army’s lawyer, Joseph Welch, to famously ask, “Have you no sense of decency?” which brought an end to McCarthy’s career.

Tyrnauer shrewdly includes an interview of Cohn’s cousin, Annie Roiphe, who sports a naughty smile as she indicates that Cohn’s interest in Schine went beyond the handsome man’s mind. Cohn had a crush on him and, given the bevy of Nordic-looking men he hired as chauffeurs, or to captain his boat — plus those he dated, hired, and slept with — Cohn tried throughout his life to recapture that lost love. Wallace Adams, one of Cohn’s boyfriends, interviewed in the film, attests to Cohn having a “type.”

Cohn may have been a self-loathing, closeted gay man, but “Where’s My Roy Cohn” also asserts that he was a self-hating Jew, rejecting his privileged family’s background and contradicting everything he was supposed to become. His self-made man image certainly helped him.

For viewers experiencing “45 fatigue,” Tyrnauer’s film offers no relief. An extended section of the film addresses his relationship with the future President, and how both men had situational ethics. Neither would ever admit they are wrong or apologize. As information about the erection of New York’s Trump Tower unfolds, “Where’s My Roy Cohn” generates righteous anger.

The film does offer some glimmers of joy as Cohn gets some comeuppance. This may not be the case when he beats an indictment, but Cohn denied having a facelift, despite noticeable scars, and he squirms whenever someone probes into his personal life and sexuality. When Mike Wallace asks Cohn about contracting AIDS, it is illuminating to watch Cohn neither confirm nor deny the truth. Moreover, a few choice clips of Cohn on TV with Gore Vidal are, as one expects, particularly delicious.

“Where’s My Roy Cohn” also offers two amazing anecdotes. One involves a Seder and reveals why Cohn probably lacks empathy and ethics. The other involves his unexpected collection of frogs, which does not exactly humanize Cohn as much as it raises more questions.

Tyrnauer’s agenda in this documentary is to present many aspects of Cohn’s life and let viewers connect the dots. He solicits testimonies from folks as varied as Roger Stone and historian Thomas Doherty, as well as journalists along with Cohn’s cousins and colleagues. Their impressions help create a well-rounded picture of a man who always wanted attention.

The filmmaker does allow Cohn’s “charisma” to shine through, not just in his smooth-talking to reporters at trials but in footage of him doing his daily 200 sit-ups in his ceiling-mirrored bedroom while reviewing his date with Barbara Walters with his male secretary. And in the film Cohn certainly gloats when he helped mobster John Gotti get a reduced sentence for murder.

But for all his dubious achievements, Cohn’s end was ignominious. He was disbarred and investigated for a fraudulent codicil, lying under oath and other crimes. He refused to acknowledge he was gay or had AIDS but received special experimental treatments for the disease at the NIH, courtesy of his friend, President Ronald Reagan.

“Where’s My Roy Cohn” addresses all these points and more in its nimble 90-plus minutes. Tyrnauer’s impressive film will not win Cohn any admirers, but it does help to better understand this controversial historical figure.