Out gay writer-director Rodney Evans’ extraordinary documentary “Vision Portraits,” juxtaposes his experiences as a visually-impaired filmmaker with three other low-vision/blind artists: photographer John Dugdale, dancer Kayla Hamilton, and writer Ryan Knighton.

Opening September 6 at the Ritz at the Bourse, his film investigates how and why blindness is not limiting for these artists. More importantly, “Vision Portraits” never gives in to the “super-crip” trope that insists its subjects are inspirational or that Evans is making a hagiography.

The filmmaker, who currently teaches digital production and other classes at Swarthmore College, has retinitis pigmentosa, which causes retinal deterioration. He met with PGN during last month’s Black Star Film Festival and explained that he originally thought his own story would be more of a framing device or an entry point to the documentary.

“I wanted to talk about my condition and experiences at the beginning and what led me to explore the creative processes of these blind or severely visually-impaired artists. What did I hope to glean from them from having a dialogue and looking at their artistic process?”

Evans’ ultimate decision to include himself in the film was not solipsistic or navel-gazing, but critical. And it came about organically. He said, “I shared a lot of experiences they went through. I know what it’s like to walk around with a red-and-white cane. I know the pros and cons and stigmas attached to that. I know what it’s like to pass for fully sighted for as long as possible — or until it becomes completely impossible.”

He continued, “That was important to acknowledge. [I] wasn’t some fully-sighted, able-bodied person coming in and doing a story on this community. I was someone from within the community that they trusted.”

Evans’ goal when making the film was to “paint a multi-dimensional, nuanced portrait of each person” and assess “what it takes for an artist to find their voice within a piece.”

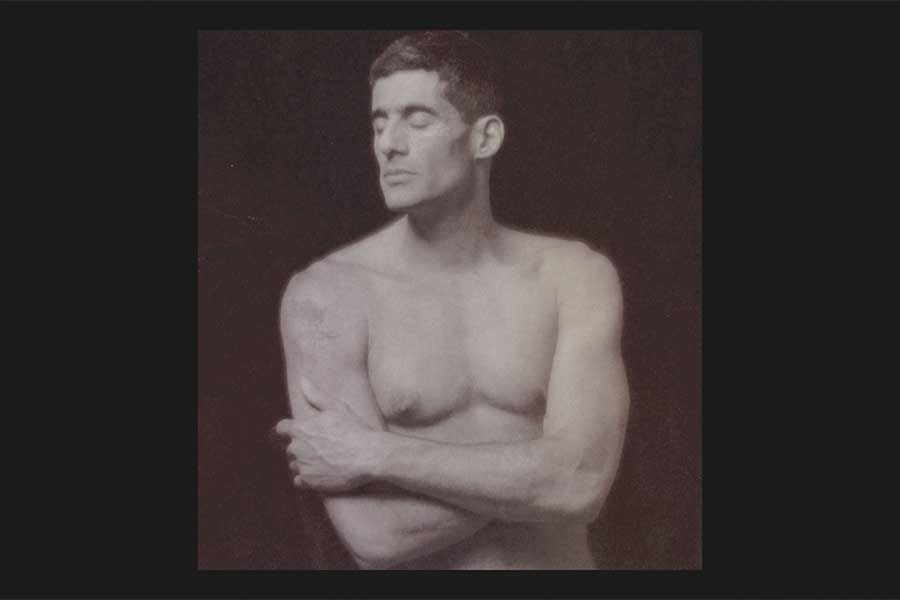

He had read Ryan Knighton’s book “Cockeyed: A Memoir of Blindness,” and found it “profoundly moving and impactful.” (Knighton is also diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa). Evans knew John Dugdale, a gay, HIV+ photographer, who went nearly blind because of CMV retinitis (an AIDS-related infection). The filmmaker recalled that Dugdale was reluctant to be in “Vision Portraits” because he had bad experiences with filmmakers in the past. But Evans explained how he convinced him to participate.

“I showed him a diary film I’d made in 1998 where I talk about coming out within a not-so-LGBT-friendly Jamaican family and the difficulties of that. And because of my vulnerability in that film, and the intimate way that story unfolds, I think that led him to trust me; that I was the right person, and I would tell the story in a respectful, tasteful way.”

As for Kayla Hamilton, Evans was looking for a woman, visually impaired, dancer of color, preferably African American, because he wanted dance to be a part of the film. He found Hamilton through a colleague and was able to film rehearsals and performances of her first solo dance piece, “Nearly Sighted” for the film.

“All of the artists have their own specific ways of dealing with blindness as subject matter or controlling the viewer or audience member’s experience of how they see their artwork. For Kayla, who only has vision in one eye, that was really important.” Hamilton asks the audience at her solo show to wear eye patches to see the dance from her perspective.

The filmmaker deliberately, and creatively, uses black screens, irises and blurred or obscured images to force viewers of “Vision Portraits” to understand what low-vision or blindness is like for the film’s subjects. These techniques never become gimmicky. They give the audience a perspective to see and experience what the subjects recount for themselves. For example, when John Dugdale describes his vision as being like the “aurora borealis,” Evans layers super-8 film stock rolling out along with flares and other abstract color washes to represent that image.

Evans explained, “Whenever we could convey visually, in a visceral way, what the character was talking about, we would do it. So when I’m on the subway and the periphery is blacked out, or made more abstracted and you see the center really clearly, it’s important for the audience to see that that was my point of view and how that differs from the fully-sighted person’s perspective, which was cut to later.”

Likewise, Evans and his cinematographer — Evans had two for the film — would hold magnifying glasses over Ryan’s book of poetry and shift the focus so words would come into focus or be obscured by light to convey his experience on stage trying (and failing) to pass as a sighted poet.

On the subject of passing, Evans remarked that he came out (in the film) as visually impaired because, “It started to feel disingenuous to not acknowledge that I had a shared experience with these specific individuals.”

He added, “It was a relief, frankly, because there was so much miscommunication and wrongly interpreted signals that put me in a dangerous position. If I’m commuting to Philadelphia for my job, and I’m going through [New York’s] Penn station and as a young Black man, I’m bumping into 12 people, that is apt to be perceived as a hostile, aggressive act. But If I’m using a red-and-white cane, that immediately diffuses the situation.”

That said, Evans indicates that his cane should not be seen as something that prevents him from being self-sufficient. After all, he did make the impressive “Vision Portraits” from scratch over five years with very little money.

When asked about finding a partner and navigating a relationship (something he mentions in the film), Evans demurs, “I’m quite independent, self-sufficient and able to take care of myself. It’s about what that red-and-white cane signifies to other people, and how it’s looked at within the gay community, which can be hung up on physical perfection as opposed to knowing someone’s personality and what they are passionate about. You don’t want to be saddled with a lot of those stigmas. But it makes it challenging, to be in a really dark bar, where it’s so dark you can’t see anyone. Where are the spaces that are accessible to people who are not able-bodied or have some form of disability, that they have chosen to disclose or not, or are visible or not?”

Evans adds, “One in four people identify as having a disability in this country but 0.2 percent of characters in film are represented with a disability. There’s this huge gulf between the lived experiences of people within this country and what’s reflected back at them in film and television. What does that erasure perpetuate? What kind of fear, what kinds of stigmas and misperceptions does that lack of knowledge from accurate representation and honest portrayals perpetuate? And what does it take to stop underestimating what a disabled person can do both in front of or behind the camera?”

“Vision Portraits” is a powerful testament to this issue, as well as Evans and other vision-impaired artists.