In the years before Stonewall and Pride, LGBT activism was criminalized and subversive. In the 1950s, Sen. Joe McCarthy (R-WI), leader of the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings, was looking for Communists.

Though McCarthy’s assistant, 26 year old Roy Cohn, was a closeted gay man, McCarthy hoped to expose gay men and lesbians as subversives — like Communists — through the “Lavender Scare.” Former U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson said that, “The so-called ‘Red Scare’ has been the main focus of most historians of that period of time. A lesser-known element … and one that harmed far more people was the witch-hunt McCarthy and others conducted against homosexuals.”

In 1950, a Senate subcommittee issued a report stating that homosexuals were a threat to national security. Homosexuality was viewed as both sick and criminal and McCarthy worked to weave the two ideas together. After World War II ended, the government dismissed about five homosexuals a month from civilian posts; by 1954, the number had grown 12-fold.

Gay men and lesbians were unsure how to retaliate. There was no model for gay and lesbian civil rights activists to follow. As renowned activist Harry Hay would later be quoted in the New York Times, “We lived in terror almost every day of our lives.”

Hay and others sought to fight that terror. Activist groups began to form, notably in Los Angeles and San Francisco, then on the East Coast in New York City and Philadelphia. One group that would make gay history in America — the Mattachine Society — was started by a handful of gay men, led by Hay in Los Angeles in 1950.

The confluence of the end of the war propelled the beginning of the movement toward gay and lesbian civil rights. Men returning from combat were granted leeway to “sow their wild oats” and “play the field,” giving closeted gay men an easy excuse for not marrying. This allowed many gay men to remain “bachelors.”

But the heteronormative confines of marriage and family were interwoven with the sense of imminent peril being proffered by politicians about Communism. U.S. involvement in the Korean War was driven by this fear, as Vietnam would be a decade later. In 1950, even the Communist Party had issued a warning about the threat of homosexuality.

The U.S. State Department declared homosexuals security risks. Even the appearance of homosexuality — masculine women, effeminate men — became grounds for firing and even arrest.

In 1950, it was not only a crime to be a gay man or lesbian with myriad sodomy and lewdness laws on the books, but the criminalizing of gay men and lesbians was expanding. Arrests were common. No-touching rules for same-sex couples in bars and clubs were enforced regularly by impromptu police raids. It was against the law to cross dress. Women had to be wearing at least three articles of women’s clothing or face arrest. The obverse was true for men.

Concomitant with the harassment and arrests were beatings, and forced sodomy and rape while in lock-up. Lawyers would charge exorbitant fees to get their clients out of jail, later blackmailing them with threats of exposure to families and jobs. Even noted civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, organizer of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s famous 1963 March on Washington, was arrested for “lewd acts and vagrancy” in 1953 after being arrested by police while with two other men in a car.

At 35, Dale Jennings was a handsome war hero and a decorated veteran of World War II. In 1953, he gave a speech to the Mattachine Society at a banquet dinner about how McCarthyism had linked Communism and homosexuality and told the story — his story — of how those two things almost ruined his life.

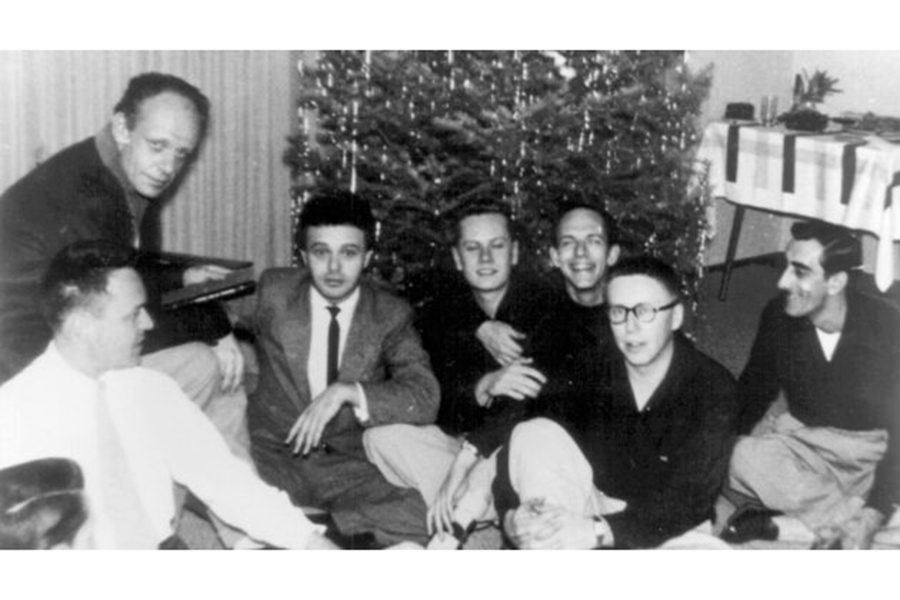

On November 11, 1950, Jennings accompanied Bob Hull, with whom he was having an affair, and Charles “Chuck” Rowland, with whom Hull lived, to meet with Harry Hay and Hay’s lover, designer Rudi Gernreich. Gernreich would later bankroll the Mattachine Society while Hay was its leader, albeit anonymously. Hay was determined to promote his ideas of a homosexual culture and concomitant activism to protect his “people.” Jennings had a different perspective — he didn’t see homosexuals as a group because he thought they were too disparate as individuals — but agreed with Hay that gay men needed protection from the onslaught of harassment and criminalization.

That night would be the first official meeting of the Mattachine Society, the first successful gay rights organization in the U.S. Hay has been called “the founder of the modern gay movement.”

Jennings was arrested in April 1952 for “lewd and dissolute” behavior. Jennings had allegedly solicited an undercover police officer in a public restroom in Westlake Park (now MacArthur Park) in Los Angeles. Undercover police entrapped gay men for years. The men involved — often married and with jobs to protect¬ — quietly pled guilty.

Although Jennings had declined the offer of sex, the man had followed him home and convinced Jennings to invite him in. Then the undercover officer signaled his partner and soon Jennings was handcuffed and sitting in the back of a police car with three officers discussing what would happen next. Jennings expected and feared a beating; police officers regularly drove gay men outside the city limits as they did with Jennings, and beat them to “help them get straight.”

Yet as Jennings recounted the incident later, the officers discussed beating him and how they would do so but most wanted to know why he was “like this,” since he was a war hero.

Hay saw Jennings’ arrest as pivotal for the Mattachine Society — a way to draw attention to the unjust treatment of homosexuals, particularly by police. Hay had been trying to start a homosexual action group for several years. Through Mattachine, Hay had already protested police brutality against Chicanos in Los Angeles. Now, one of their own, a founding member of Mattachine was at risk: Jennings refused to plead out, and his case was held over for trial.

Jennings was the first man to fight such a charge.

Jennings’ arrest put the issues of criminalization of homosexuality, as well as the myriad false arrests in a context activists related to easily. Desperate to have the charges dropped so damage wouldn’t be done to his budding career as a screenwriter, Jennings called Hay who bailed him out of jail. The day after his arrest, Jennings and Hay had breakfast together at the famous Brown Derby restaurant. By the end of the meal, the two men committed to fighting the charges against Jennings and clearing his name.

According to the Mattachine Archives, Hay mobilized Mattachine to help Jennings. He established the Citizens’ Committee to Outlaw Entrapment and Long Beach attorney George Sibley, a labor attorney Hay knew, was hired to defend Jennings in the first-ever case of its kind.

It was a surprisingly long trial, given the charges. Ten days of testimony revealed the corruption in the LAPD and how homosexuals had been specifically targeted by the LAPD because vice busts were easy, homosexuals were despised and most would do anything to avoid exposure.

Both Jennings and Hay got what they wanted out of the trial. The jury deadlocked 11 to 1, for acquittal, and the judge acquitted Jennings of all charges. The judge and jury took the LAPD to task, stating unequivocally that the LAPD had acted with deliberate malice toward Jennings and the LGBT community in general. The judge called the entrapments and bar raids nothing short of “persecution.”

For Hay, the rebuke by the court codified what he believed: homosexuals were a “people,” a group unto themselves. Word of Jennings’ acquittal spread and the Mattachine Society membership grew exponentially. The publication of ONE magazine by Mattachine (printed in Jennings’ brother-in-law’s basement) also helped disseminate information on the breadth of issues that needed to be addressed by gays, notably continuing harassment by government and police.

ONE magazine would bring yet another court battle in 1954 when the United States postmaster in Los Angeles confiscated it as “obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy.” In 1958, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed lower court rulings upholding the post office, finding in favor of ONE.

While Mattachine eventually disbanded and the budding Gay Liberation Front took hold in the 1960s and 70s, Mattachine, Hay and Jennings ultimately altered history with their focus on decriminalizing homosexuality.

Both would live to see sodomy laws overturned in the landmark 1993 U.S. Supreme Court case, Lawrence vs. Texas, which was predicated on the same police entrapment that had fueled their fight for justice.

McCarthy died of alcoholism at the age of 48. Jennings died in 2000 at 82 and Hay at 90 in 2002. n