Few figures in the Philadelphia LGBTQ community are more evocative of the words “road to Stonewall” than Kiyoshi Kuromiya.

Born in the Heart Mountain Relocation Camp for Japanese Americans in Wyoming in 1943, Kuromiya would later tell gay historian Marc Stein in an interview, “I don’t remember a thing about Heart Mountain, although in 1983 my mother and I visited the site of this concentration camp, which the government called a relocation center for Japanese Americans during World War II, two-thirds of whom were American citizens.”

In 1992, Kuromiya received his $20,000 reparations check from the United States government for that atrocity.

Kuromiya told Stein, “I am fascinated with that part of history and I’m sure it affected my own activism and my own attitudes toward our government, war and racial issues.”

Kuromiya moved to Philadelphia from his family’s home in suburban Los Angeles in 1961 to attend the University of Pennsylvania. He was on a full scholarship and studied architecture. He worked with the renowned Buckminster Fuller and would go on to co-author a book with him. He also immersed himself in first the black civil rights movement, then the antiwar and gay liberation movements.

Before dying from cancer in 2000 at only 57, Kuromiya would become one of the premier AIDS activists in the U.S. and a face of AIDS activism in Philadelphia.

At Penn, Kuromiya protested the draft and Vietnam War and became romantically involved with other men. He would later describe those early years in Philadelphia as formative of both his activism and opportunity to live openly as a gay man. He was a co-founder of Gay Liberation Front Philadelphia and a member of Students for a Democratic Society.

Kuromiya participated in the first “homosexual” rights action in front of Independence Hall on July 4, 1965. The same year, Kuromiya marched with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. at Selma. He described his relationship with King as one of a close confidant, and Kurmiya was a caretaker for King’s children, Martin Jr. and Dexter, after King’s 1968 assassination.

On March 13, 1965, Kuromiya led a group of high-school students in a march to the state capital building in Montgomery, Alabama. There were attacks on the marchers by Alabama state troopers and Kuromiya was hit with billy clubs. In a Life magazine profile, Kuromiya described his experience: “I was in the South during the spring and summer of 1965. After Reverend James Reeb was killed, we marched and I was clubbed down and hospitalized.”

Kuromiya said the experience illuminated his perspective on oppression, asserting, “When you get treated this way, you suddenly know what it is like to be a black in Mississippi or a peasant in Vietnam. You learn something about going through channels then, too. I gave my story to an FBI agent in the hospital. He took seven pages of notes, but I remember thinking at the time it was probably just about as effective as relaying information to the ACLU via the House Un-American Activities Committee. Nothing ever came of it, at any rate.”

To protest the use of napalm in the Vietnam war in 1968, Kuromiya sent out flyers saying a dog would be burned alive in front of Penn’s Van Pelt Library. Thousands turned up to protest, only to find a message from Kuromiya: “Congratulations on your anti-napalm protest. You saved the life of a dog. Now, how about saving the lives of tens of thousands of people in Vietnam?”

Kuromiya also served as an openly-gay delegate to the Black Panther’s Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention, held in Philadelphia in 1970, at which he presented a workshop on gay rights.

Kuromiya would say later, “The white middle-class outlook of the earlier [homophile] groups, which thought that everything in America would be fine if people only treated homosexuals better, wasn’t what we were all about. …We wanted to stand with the poor, with women, with people of color, with the antiwar people, to bring the whole corrupt thing down.”

In the mid-1970s, Kuromiya survived a battle with lung cancer and soon after began touring the country with Buckminster Fuller through 1983 when Fuller died. Kuromiya collaborated on six books with Fuller. As Kuromiya told Stein, “I really believe that activism is therapeutic.”

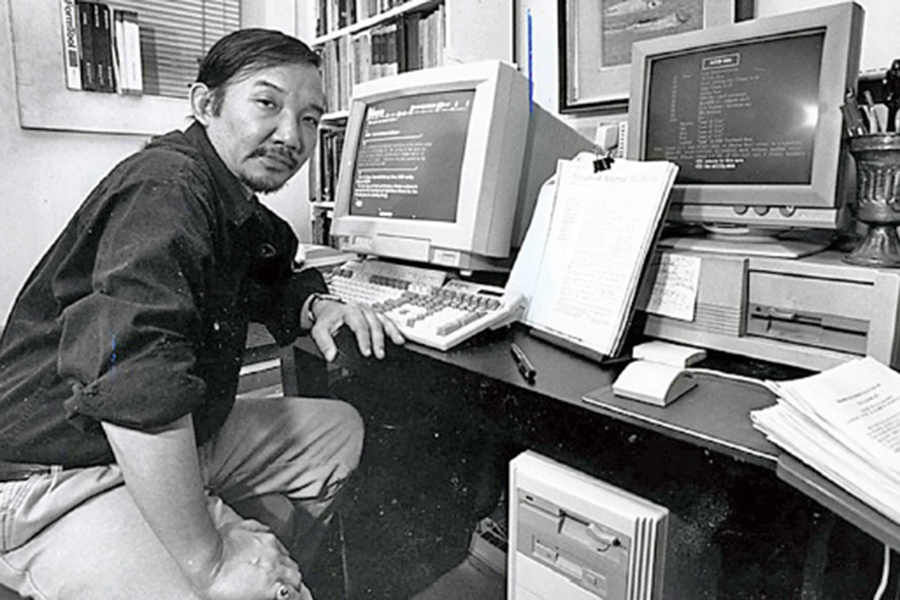

The 1980s led Kuromiya into AIDS activism as the founder of the Philadelphia chapter of the direct action activist organization, ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). In 1989, Kuromiya was diagnosed with AIDS, which intensified his activism. He repeatedly said, “Information is power, “ and founded the Critical Path Project, an HIV/AIDS resource organization that provided information and a 24-hour hotline for the Philadelphia gay community. The Critical Path newsletter, one of the earliest and most comprehensive sources of HIV treatment information, was mailed to thousands of people living with HIV worldwide. Kuromiya also sent newsletters to hundreds of incarcerated individuals to ensure their access to up-to-date treatment information.

Kuromiya was a pioneer of national and international AIDS research advocacy, and his loving and compassionate mentoring and care for hundreds of people living with HIV was world-renowned. Kiyoshi was the editor of the ACT UP Standard of Care, the first standard of care for people living with HIV produced by PWAs.

During the 1990s, he was involved in several impact litigation cases: a successful lawsuit against the Communications Decency Act to maintain the right of free speech on the internet and Kuromiya vs. The United States of America, a Supreme Court case in which he argued for the legalization of marijuana for medical use by people with AIDS. In 1993, Kuromiya was arrested after protesting at the Capitol in Washington, D.C. and at the White House on behalf of people with AIDS.

“I’m in the back of the police van on the way to the police station from the White House. We were mostly people with AIDS in that van and one of the plastic handcuffs were on too tight and was cutting off circulation and this person was scared, so of course I slipped out of my handcuffs. And of course, everyone thought I was Houdini at the time. I said, ‘No, I’m used to this. I know exactly what positions to put my hands in as they’re putting them on, and I can get out of it.’ I borrowed someone’s nail clippers and got everyone else’s off.”

Philadelphia author, activist and archivist, Tommi Avicolli Mecca was a close friend of Kuromiya’s. He summed up Kuromiya’s activism succinctly. “Kiyoshi was a lifelong activist who saw the intersectionality of issues, cofounding Philadelphia GLF, going south on the freedom rides, marching with King in Selma, opposing the war in Vietnam and all war, and, of course, fighting against AIDS in the 80s and 90s.”

Avicolli Mecca added that Kuromiya’s work was broad, encompassing and fundamentally queer, “Kiyoshi wasn’t about assimilating into the dominant heterosexual culture. He was about changing a system that oppresses so many people that put profits over human needs. That will always be his legacy.”