Jonathan Katz’s participation in a gay liberation organization during the 1970s spurred his passion for researching LGBTQ history.

A native of New York City’s Greenwich Village, Katz joined the Gay Activists Alliance in 1971. He then wrote the documentary play “Coming Out!” which was performed the following year at the group’s firehouse.

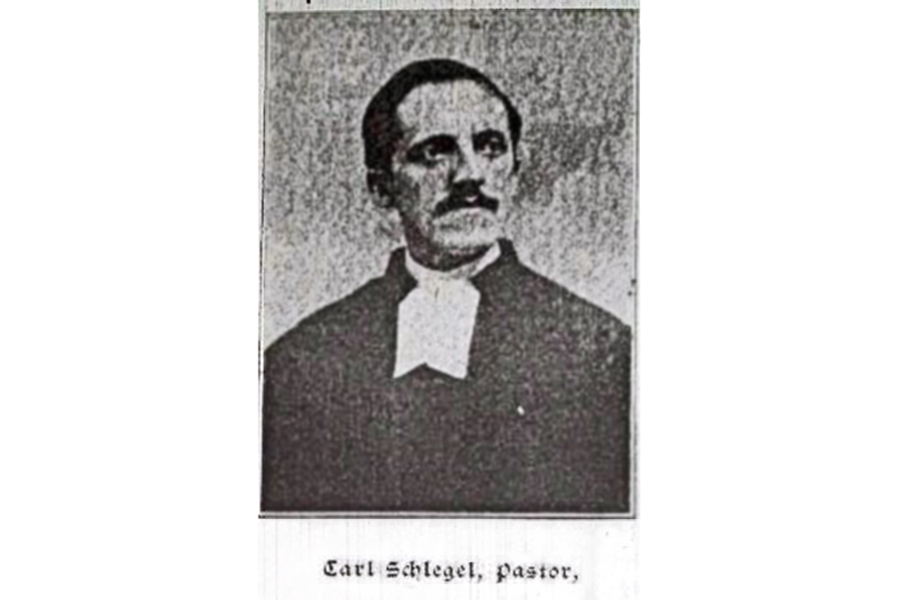

Katz’s interest fueled his recent discovery at Philadelphia’s Presbyterian Historical Society. There, the LGBTQ historian found new evidence supporting the theory that Rev. Carl Schlegel, a German immigrant to the United States, publicly defended gay rights in New Orleans in 1906-07 — making him the earliest-known gay rights activist in the country, Katz said.

“I love the detective work of doing historical research, and I love trying to figure out what it all means,” Katz said. “Not only the recovering of the documents, but looking at the language, the particular words that Schlegel used. …It’s a way I feel connected to other people, other researchers.”

Schlegel, a Presbyterian minister, was known for advocating for the LGBTQ community in the early-20th century and distributing publications by the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, a historic Berlin-based gay rights organization. The group later inspired fellow pioneering LGBTQ activist Henry Gerber to found the Society for Human Rights in Chicago, the country’s first gay liberation organization, in 1924.

A New York church fired Schlegel from its ministry in 1905, likely for promoting ideas of gay acceptance and LGBTQ literature, Katz found. He was sent to New Orleans where members of the Presbytery of New Orleans voted him guilty of “sin” and fired him in 1907 for similar offenses.

Katz’s findings came from “The Minutes of the Presbytery of New Orleans,” a document in the historical society’s archives that detailed the meeting of some of the city’s Presbyterian church officials.

The minutes outline Presbytery members dubbing Schlegel guilty of defending “the lawfulness and naturalness of the condition, and in some cases of the actual practice of homo-sexualism, Sodomy, or Uranism.”

“Uranism” was an iteration of a 19th-century German term for a man sexually interested in other men, according to Katz’s findings. Schlegel was quoted as advocating for “the same laws” for “homosexuals, heterosexuals, bisexuals, [and] asexuals” — introducing terminology that was still considered innovative at the turn of the 21st-century.

“The recovery of the early history of activism about homosexuality, of the proselytizing for law reforms in the U.S. and England and other countries is especially important to recover because it’s an inspiration to today’s activists,” Katz said. “To know that people were striving long, long ago…to do something that people only achieved many years later.”

Katz has authored four books on the history of sexuality and his own memoir, “Coming of Age in Greenwich Village.” He has taught a class on sexual history at Yale University, as well as courses at New York University and The New School, and headed faculty discussion groups at Princeton University. Katz has also spoken at a conference on LGBTQ history at Harvard University.

While Katz determined Schlegel’s “valiant and daring” activism appeared to have no lasting societal impact, there’s still much to be learned from him, Katz said.

“It’s not that he was successful in changing peoples’ minds, but he tried,” Katz said. “Lots of good work is not recognized or not successful, but it’s worthy to devote your life to, whether or not you are successful. Hopefully, you will help to create a slightly better world through your activity, a slightly freer world, a slightly more pleasurable world.” n