In a reversal of its decision, the Philadelphia Historical Commission voted to list a former bathhouse on the city’s Register of Historic Places.

This designation also is historic for another reason: It marks the first time that a building in Philadelphia will be listed, at least in part, because of a historical connection to the LGBTQ community.

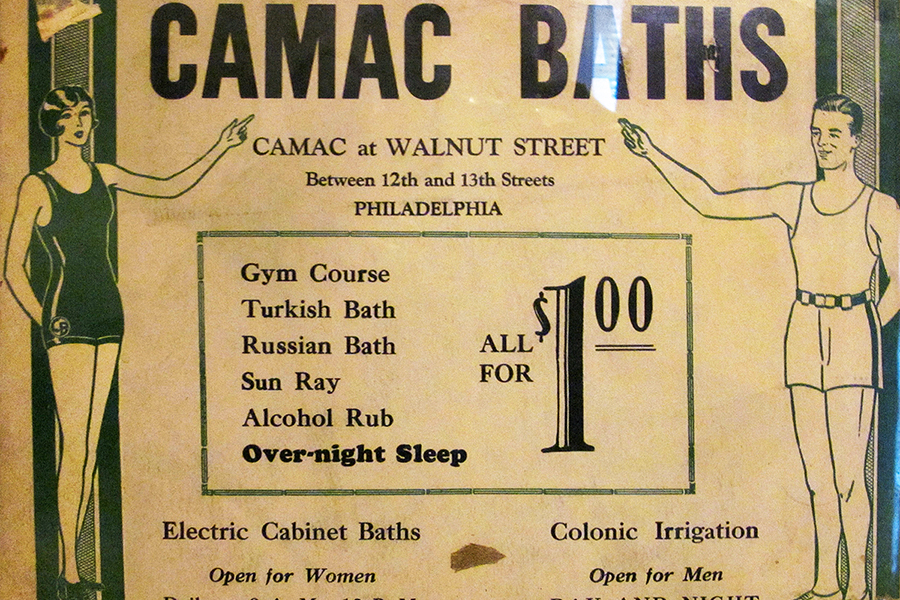

The building once known as the Camac Baths sits on the southeast corner of Camac and Chancellor streets, between 12th and 13th streets, in the heart of the Gayborhood.

The building has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since 1984 for contributing to the East Center City Historic District.

While the building had undergone significant change since its original listing, a subsequent update of the East Center City Historic District in 2017, approved by the National Park Service, reaffirmed that the Camac Baths retained integrity sufficient for national historical status.

But when, last September, historical-preservation group Keeping Society of Philadelphia nominated the structure for the Philadelphia Register, controversy arose around the word “integrity.”

In February, the staff of the Philadelphia Historical Commission rejected the nomination, arguing the Camac Baths had “lost integrity” sufficient for listing in the Philadelphia Register. PHC cited that the building had been changed too much from its original form.

“The three structures included in the nomination, which were not purposely built as either a bathhouse or clubhouses, have lost any historic character and integrity they may have had from their many unsympathetic alterations,” PHC said in a statement then. “Owing to their lack of integrity, they fail to inform the public of any historical significance they may have had and therefore fail to qualify for designation.”

But the mayoral-appointed Committee on Historic Designation, an advisory committee of pedigreed cultural and architectural historians, disagreed with the PHC report and recommended the Camac Baths for designation at their meeting in February.

This intervention came on the heels of Mayor Jim Kenney’s announced intention to strengthen the city’s efforts at historic preservation, and it convinced the PHC to table the final determining vote until its April 12 meeting.

“Of the 23,000-plus properties listed on the Philadelphia Register, the Camac Baths is one of the first, if not the first, to be individually nominated for significance related to LGBTQ history,” said Oscar Beisert, architectural historian and project director at the Keeping Society.

Historical research has uncovered that the Camac Baths served as a discreet gathering place for gay and bisexual men as early as 1938 and continued through the 1950s.

The diaries of Christopher Isherwood (1904–86), the English-American novelist, confirm that the building was a known, though discreet, meeting place/venue for gay/bisexual men, accessible even to new and temporary residents of the city. Isherwood himself frequented the Camac Baths between 1941-42.

According to Beisert, historical research shows that “this building is significant as one of the earliest known and documentable meeting places/venues for gay/bisexual men in Philadelphia, representing the period before establishments in the city could or would openly serve the LGBTQ community. Because documenting this type of meeting place/venue at such an early date is difficult and unusual in Philadelphia and at-large, it is critical that the Camac Baths be recognized as representative of the period when homosexuality was illegal and not even marginally socially acceptable.”

The building continued holding a significant connection with Philly’s LGBTQ community through recent years. From 1990-97, it was home to the city’s gay community center, then known as Penguin Place.

Today, the facility houses the relocated 12th Street Gym, long one of the community’s primary fitness venues.

Beisert was jubilant at the vote, if somewhat surprised. He thought it unlikely that PHC would reverse its previous opposition. But now that it has, he said, this could be the first of many such listings.

“Of the more-than 23,000 historically certified buildings in Philadelphia, you know there’s got to be a number of them with historical ties to the LGBTQ community. It’s time they were recognized.”