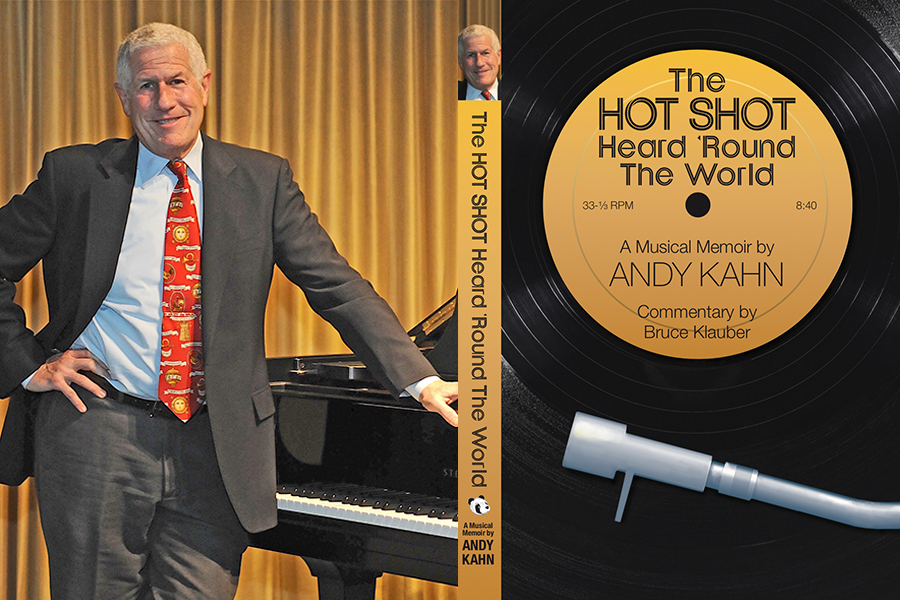

Jazz legend and international disco sensation Andy Kahn splits his time between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, but still found time to pen a musical memoir.

In “The Hot Shot Heard ’Round the World” — named for his legendary 1978 dance hit “Hot Shot” — the proudly out Kahn presents a warts-and-all showcase of the music business, the gay disco scene, Philadelphia and beyond.

The author is scheduled to speak, play and sign his truth at Shakespeare & Co. on April 18.

PGN: To start, why a memoir?

AK: You know how people remark, “You oughta write a book!” I had no idea I was going to do that. Nine years ago, my friend and drummer Bruce Klauber — during a conversation he and I were having about what happened to the music industry when digital recording conquered analog — suggested I write an article about it. He suggested trying to place it in Jazz Times. So I did. When he submitted it, we were informed it was too long for a single article and would be better if written as a series, perhaps in three or four parts. Not considering myself at the time to be a writer in the journalistic sense, I took the task at hand. When I finished, we were told it was now too long for a series of articles and felt more like a short book. And thus, the beginning of a recollection of stories began to take shape, evolving into a memoir with the emphasis on music and the music industry’s influence on my life.

PGN: What, beyond age and memory, made you decide to write?

AK: I was 57 at the time. My partner Bruce and I were in Fort Lauderdale at the end of November in 2008, escaping from having to endure another family holiday dinner. While Bruce was lounging by the pool, I was in the room of the hotel and began to write down my thoughts about the evolution of recording techniques into the digital realm and the effect it had on everyone in the music industry a decade earlier.

PGN: What can you say about being a child actor in your youth? It sounds like nothing but horror in the 21st century.

AK: Being a child actor was never a horror story for me. It was an eye-opening period. Introduced to alternate lifestyles, free love exchanged between different generations of human beings, drug and alcohol ingestion and dramatic personalities — from primadonna to tyrannical — made me want to experience everything. That began when I was 9 years old. Smoking hashish in the original Theatre of the Living Arts. When it was reborn from a shuttered movie house to a spanking-new repertory theater in 1961, it was not something most 10-year-old boys were given the chance to experience.

PGN: Having such a high-minded background in jazz and classical piano, did disco seem like a step down in its composition or approach?

AK: Please do not imply that I had much to do with classical piano instruction! My lame efforts at attempting to acquiesce to the classical teachers my parents sent me to were very short-lived and completely unsuccessful. But … not at all. Disco offered many true jazz musicians the opportunity to be creative with their harmony, arrangements and compositions — simply presented over a driving, infectious rhythmic background that encouraged people all over the world to get up and dance.

PGN: I didn’t realize there was so much backstabbing around your 1978 disco hit “Hot Shot.” To give readers a taste: The record broke and you were a sensation. What was the downside?

AK: Having slid in with a monster international hit record as a previously unknown producer/arranger/songwriter — and believing that now all doors would be wide open for future projects. The reality of finding oneself suddenly under the microscope made everything daunting. What crawled out of the woodwork, with every design at undermining the success that “Hot Shot” had achieved by two unknown producers/songwriters and an unheard-of female vocalist, was vermin, the likes of which I’d never experienced. Even in the theater — where I got to see individual backstabbing occur regularly — the vicious and underhanded techniques employed by record-industry shitheads remains unparalleled for me. The lowest form of humanity occupies the record industry. There, I’ve said it. I hold fast to that opinion.

PGN: You seem to revel in entrepreneurship. How and why did that become important?

AK: Whether it was my first business at age 9 in doing electrical repairs and installations in the neighborhood, to creating brand-new recording studios from the ground up, to taking over my family’s paint and decorating business during my 25-year hiatus from performing in public, entrepreneurship must course through my veins like water travels through the stretch of a garden hose.

PGN: No matter what else you were doing, both Bruce Klauber and Bruce Cahan seem to be always part of your life.

AK: Funny how that is. It’s deeply investigated in the book, but Klauber taught me how to swing, at age 10. That is one of the most important factors to my personality — musically and personally. Understanding the authentic and in-depth meaning of Duke Ellington’s composition “It Don’t Mean A Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing” is what makes my world go around. For this, I am unilaterally and permanently indebted and grateful. Bruce Cahan taught me how to love. I thought I had loved others before him. In fact, I’m sure I did, but not on this level. This is a love of life spent together — as a couple. The effect we know we have on others and the spin of the cosmic universe, in turn, is something we revel in, cherish and wish that everyone else on this planet can achieve and appreciate.

PGN: What new chapters are being written as we speak?

AK: Every day I feel as though I’m composing a new song, chapter or arrangement. My life continues to be challenging and rewarding. The old sayings of not giving up, of seeking your personal goals and absolutely achieving them because failure is not an option, remain valid, truthful and believable. When the combination of those elements ceases for me, and you’re in the neighborhood — please, call 911.