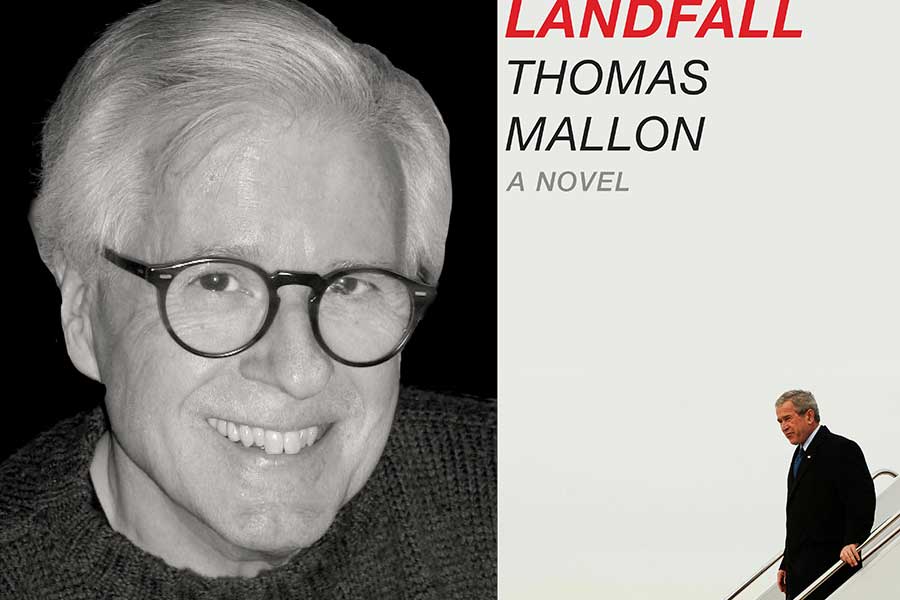

Thomas Mallon is not only an icon of the journalistic arts-and-trade and a one-time titan of Republican thought (“I staggered out of bed on the morning of Nov. 9, 2016, went online to the D.C. Board of Elections site, left the Republican Party and changed my registration to Independent”). He also is a famously out gentleman who in his newest book, “Landfall,” gnashes into the George W. Bush presidency and the woes of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina with brio and smarts.

The author will discuss the book at the Parkway Central Library of Philadelphia 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, March 27.

PGN: I know you once described yourself as a Libertarian Republican, which I get. Just for the heck of it, how does the Trump administration feel to you at present?

TM: The Trump administration is an unmitigated catastrophe for every single American.

PGN: All things LGBTQ move subtly and somnolently through your work. Is that due to wanting to steer clear of your own life or form of the autobiographical?

TM: It’s really different from book to book. My own life wouldn’t bring much excitement to fiction; history offers much better subject matter. But one is always present in one’s books in some way or another. In Finale, the volume of the trilogy set in the Reagan years, there’s a character named Anders Little who’s coming to terms with being gay. He’s also a foreign-policy conservative who works for the National Security Council. He may not like the Reagan administration’s policies on AIDS — I myself was appalled by them — but he sees Reagan as someone actively extending freedom to hundreds of millions of people by putting intense pressure on the Soviet Union and Communism. He chooses to serve that cause.

PGN: Back in the time of ‘Fellow Travelers,’ you wrote: “Having more than once described the writing of historical fiction as being a relief from the self, I was aware as I worked on ‘Fellow Travelers” of venturing further than usual into my own life’s preoccupations and fundamentals, however refracted they might be here by time and geography.” What were those newer preoccupations, then, and how have the affected your work?

TM: In “Fellow Travelers,” I was writing very consciously about a young man, Timothy Laughlin, whose life I envisioned as what my own would have been had I been born twenty years earlier. (One of the first notes I made about him was “Born: Nov. 2, 1931.” My own birthdate is Nov. 2, 1951.) He is Catholic, temperamentally conservative, and also madly in love with another man; he doesn’t see any contradictions among those things, no matter how strongly — and dangerously—the world insists they are incompatible. I have always been engaged by political issues, especially those involving foreign policy. In that sphere, the Nixon, Reagan and George W. Bush administrations were all tumultuous and transformative. I try to dramatize the enthusiasms and ambivalence of a whole range of characters as they confront the changes — and some of my own attitudes get dramatized along the way.

PGN: Did you know when you started the trilogy that Landfall is where you would wind up?

TM: It’s a sort-of accidental trilogy. Watergate led to the Reagan book, but I didn’t think that there would be a third volume after that. It arose out of discussions with my editor, who began thinking of the books as a trilogy before I did. If I’d known it was going to be a trilogy from the start, I’d never have called what turned out to be its middle volume Finale.

PGN: The diversity of writing the details and detritus of three Republican presidents as fiction – what did you find that united them, and their thought and work processes?

TM: I tried to see all three of these Presidents at the lowest point in their fortunes: Nixon during Watergate; Reagan during Iran-Contra and the collapse of the Reykjavik summit; Bush during the Iraq insurgency and Hurricane Katrina. In terms of their personalities I was more struck by differences than similarities. Reagan was the most mysterious, the only one of the three I did not try to get “inside.” He’s seen from the perspectives of the people around him — rather as Gore Vidal tried to do in his novel about Lincoln — instead of from his own consciousness.

PGN: What was the greatest challenge of writing Bush Jr. as comical without being oafish?

TM: What interested me in him as a character was the alternation of different sides of his personality: the wisecracking good ol’ boy was a genuine part of him; so was the short-tempered impatience with colleagues, press, etc. — he is very much his mother’s son.The speed with which these sides of himself alternated struck me as unusual — and probably exhausting for him. I think that painting, which he took up seriously several years after leaving office, had an enormous effect on him. He writes movingly about how it caused him to discover shadows for the first time. I think he became calmer, less absolutist; a more even person. I think he’s a complicated, decent human being — which is how Michelle Obama regards him.

PGN: Of all of his staff, why choose Condoleezza Rice to be … not so much a moral center … but a safe haven for smart comic relief, as if she is looking in from outside?

TM: Rice fascinated me as a strenuously self-disciplined over-achiever, a poignant figure who was under tremendous personal and cultural pressure to be perfect. At the same time, she was caught between the two powerful figures of Rumsfeld and Cheney — neither or whom regarded her highly. Her attempts to remain influential with the President were a daily strain and challenge. She was exceptionally guarded, and remains personally unknown to most of the American public.

PGN: In creating two fictitious characters — O’Connor and Weatherall — create a distanced set of observations that wind up as more truthful to what was/is on your mind regarding W.

TM: What I tried to do with those two characters was to show the moral complexity of some of the big issues of the Bush years. Ross Weatherall starts out as a true believer in Bush; but his experiences in New Orleans disillusion him. Allison O’Connor is at first a sarcastic skeptic when it comes to all things Bush, but her experiences in Iraq make her believe that something has to be salvaged from the botched occupation, and she becomes much more sympathetic to the administration’s later efforts there. The novel contains a number of well-intentioned people (I think the president was one of them) who were trying, and often failing, to do what they thought was right.

PGN: So what does the nonfiction Thomas Mallon appreciate about that Bush presidency?

TM: I disagreed with the administration on any number of things, such as gay marriage — Bush’s VP Cheney, by the way, supported gay marriage well before Barack Obama did. And I think that Bush ultimately overreached in Iraq. But I think one can argue that Obama’s underreachings in the world (his reluctance to intervene in Syria) did at least as much damage. Historians will have to sort this out. What a novelist can do is try to dramatize the characters involved — and allow the reader to consider the human dimensions and personal flaws that lie behind all political actions.