James Ijames is exhausted, and rightly so.

“If I’m going to do something, I’m putting my heart and soul into it,” he said.

Fatigue is part of the equation of being in theater, and the out Philadelphia performer and playwright understands it all too well as he wraps up one project and gets another underway.

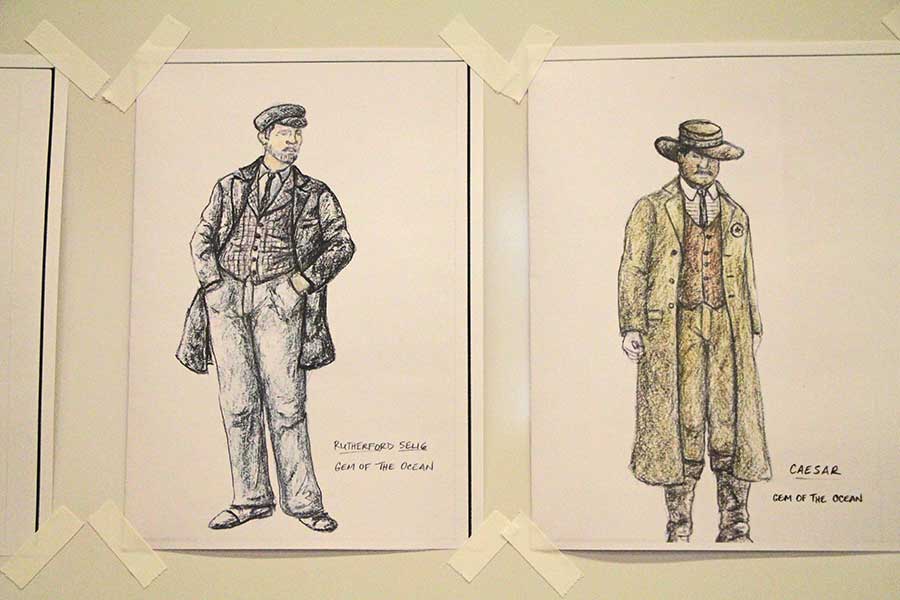

As his play “Youth” completes its run at Villanova University (where he’s also an assistant professor of theater), Ijames has been rehearsing actors at the Arden Theatre Company for his adaptation of August Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean.”

Ijames has a reputation as one of Philly’s most in-demand and acclaimed artists. He has won prestigious awards, including the 2011 F. Otto Haas Award for Emerging Artist and three Barrymore Awards: Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Play for “Superior Donuts” and “Angels in America” and Outstanding Direction of a Play for “The Brothers Size.”

Yet, while he multitasks and prepares for “Gem of the Ocean” to be staged Feb. 28-March 31, he manages to stay humble.

“I certainly don’t think I can cherrypick, but I do think that I am at a point where people trust and take a chance on me,” said the director, referring to the back-and-forth that theater companies typically afford him. “Those moments of working real hard, to the best of my abilities, have led me to this point. I’m certainly not at a point, however, to say I’ll do that and not do that.”

Even before he started directing the Wilson piece, Ijames was occupied in the past year with plays he has written himself, including “Kill Move Paradise” at the Wilma and “Youth” at Villanova. He describes them as disparate works threaded by elements of spirituality.

“‘Kill Move Paradise’ comes out of my own anxiety of being a black body in America now,” he said, explaining he was inspired to create the storyline of a netherworld-based drama in 2015 after white-supremacist Dylann Roof murdered parishioners at a Charleston church.

“I felt anger, but also felt a great deal of fear. My grandmother and mother go to Bible study each week. That’s not far-fetched that they could be those people. Couple that with my complicated sense of religion and me writing about black people in a liminal space, which means their humanity is fore-fronted. The only thing the audience of ‘Kill Move Paradise’ could trust is those four black bodies in space.”

At another end of the spectrum, he said, “‘Youth’ is about where and how faith is made, and maintained. It’s about a group of kids with one disruptor who seemingly can do a thing that only people of great faith can do — perform miracles. At the same time, he claims to not believe.”

Ijames wondered aloud: When audiences are gobsmacked with such complexity, is their faith made stronger or weaker? He said the overriding themes of his most recent plays involve the relationship between the spiritual and the earthly, as well as testing the limits of things that don’t make sense as one’s responsibility in the world.

“One play grapples with the political using the spiritual and the afterlife, while the other uses the supernatural squarely to test life’s big questions,” he said.

Ijames noted that Wilson seemed to use magic reality to test life’s limits and his era’s levels of justice and redemption. Namely, he did that in “Gem of the Ocean,” the turn-of-the-century installment of his 10-play chronicle, “The Pittsburgh Cycle.” The trek to Pittsburgh’s Hill District touches on elements of healing and spiritual awakening more so than other plays (such as “Jitney”) in “Cycle.”

“One of the first monologues that I learned and acted was from his ‘Seven Guitars,’” Ijames said. “I didn’t understand it at all — Floyd’s monologue — but it was beautiful. Wilson’s are the first plays I read of my own choice in high school. When I went to Morehouse College, one of the first full plays I did was ‘Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.’ Wilson was magical in the way he spoke. These were life-shaping moments to me.”

As a playwright, Ijames said, he was deeply affected by Wilson’s work. And while, as a writer, he aspires to turn out such works as “Gem of the Ocean” — another great leap invoking magic to tell a story — as a director, it was tricky.

“There are moments of violence and magic, and that one thing. But now I have to stage them. So what do I believe about how magic looks set next to realism? What do I believe about something that sounds like realism sitting next to poetry? Marrying all those things together — no, they’re not all that different — you count on the ability of humans to find the divine in things here, and in one another.”

“Gem of the Ocean” is also priceless to Ijames and appreciative audiences because of its contemporary language, feel and frankness. Things have not changed too drastically between the play’s 1904 setting and the present day. What keeps striking the director during rehearsals is how current “Gem” remains.

“This battle between what law and order looks like — represented by the Caesar character in this play — and the way in which it is enacted on black and brown bodies different from other folks is very much inside the core of ‘Gem of the Ocean’” said the director. “How do we create an altruistic society? How is a house a place of sanctuary at a time where we’re talking about walls? Who is allowed and who is not? Those questions are a part of ‘Gem’ — questions that still resonate today.

“It is Wilson’s most contemporary play, especially in its depiction of women. I think that Wilson is interested in the future, and he can do that because he is at the beginning of his century. He can write on the precipice of one century with access to history and expectation.”