Philadelphia was inching closer to becoming the first city in the United States to open a safe-injection site to address the city’s opioid crisis. But the project has hit a roadblock — the U.S. Department of Justice.

Pennsylvania’s top federal prosecutor last week announced he was suing the nonprofit facility called Safehouse — with timing that coincided with an executive director being named and the start of fundraising.

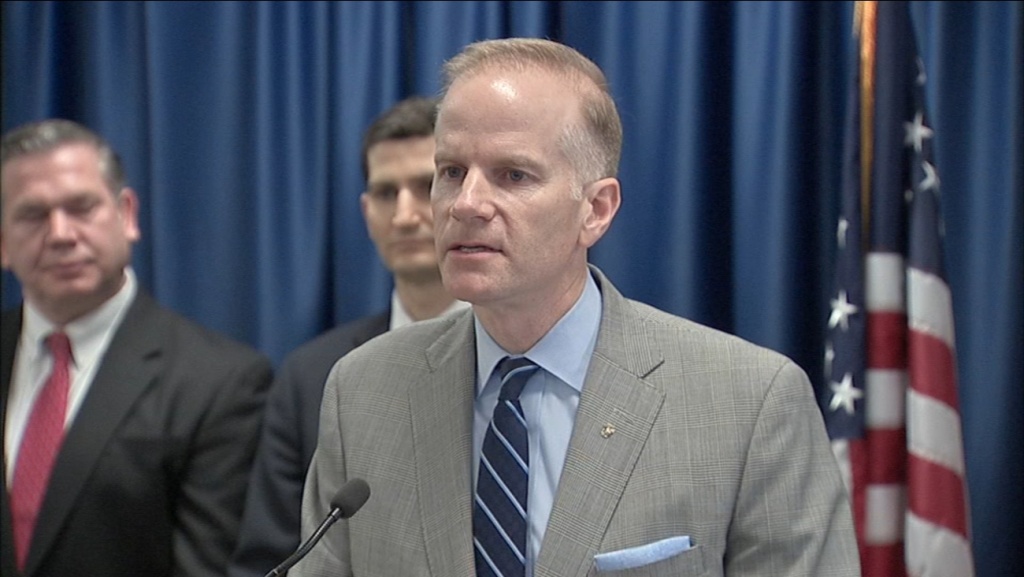

The lawsuit, initiated by U.S. Attorney William M. McSwain, would ask a federal judge to decide if a safe-injection site would violate The Federal Analogue Act, a section of the U.S. Controlled Substances Act passed in 1986, and therefore be illegal. Enacted during the height of the crack epidemic, the federal statute prohibits the opening of a facility for the purpose of making, distributing or using controlled substances.

“These deadly drug-injection sites undoubtedly do violate the law,” McSwain said during a news conference in Center City last Wednesday. “It is the [Justice] Department’s job to promote and enforce the rule of law, not to look the other way. Normalizing the use of deadly drugs like heroin and fentanyl is not the answer to solving the opioid epidemic.

“If Safehouse wants to operate an injection site, it should work through the democratic process to try to change the law,” he added.

Those behind the effort to open Safehouse said McSwain’s interpretation of the legislation is skewed.

“We’ve looked at the law that the U.S. Attorney refers to and it’s very clear on its face that you may not maintain a premises for the purpose of using controlled substances — and we don’t have an intention of doing that,” said Ronda Goldfein, vice president and secretary of Safehouse and executive director of AIDS Law Project of Pennsylvania. “We have an intention of maintaining a premise for the purpose of saving lives — and immediately saving lives. And those are dramatically different kinds of situations.”

Goldfein explained that Safehouse — which likely would be located in Kensington, where the highest incidence of overdose deaths are occurring — would be a medically supervised facility that offers not just a safe injection space, but also an observation room with counseling services, medication-assisted treatment, healthcare referrals and First Aid to treat common user afflictions like injection-site wounds.

“It’s very similar to your basic public health clinic,” she said. “We’re going to create an environment where people feel safe and trusted and protected. The hope is that one of those days they come in, they’ll say, ‘Today’s the day that I’m gonna try to get treatment and reclaim my life.’”

Statistics for safe-injection sites in Europe and Canada make a strong case for Philadelphia. A study out of the University of British Columbia and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS found that in the two years after the opening of a safe-injection site in Vancouver called Insite, overdose deaths were reduced by 35 percent in the surrounding neighborhood and 9 percent in other parts of the city. It has also increased access to drug treatment by sending 443 people to treatment in 2017, according to numbers released from the Insite.

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health estimates that 1,100 people died from opioids in Philadelphia last year, earning the city the highest opioid-death rate of any major town in the United States.

Data from 2015 National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health shows that people who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual are three times more likely to develop an opioid-use disorder compared to heterosexual adults. Goldfein says that a center like Safehouse would provide users direct access to treatment. It would also help to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS.

“The site would be offering clean-injection equipment, which has been shown to work over the 26 years that Prevention Point has been in existence,” she said, referring to the local syringe-exchange program that’s also behind the Safehouse initiative. “In that time, HIV contraction related to intravenous-drug use went from 50 percent to less than 5 percent. So we know that making clean syringes available works.”

The lawsuit filed by McSwain — a President Trump appointee — is being pursued by prosecutors in Pennsylvania and the U.S. Department of Justice, making it the first time the federal government has intervened in a case regarding safe-injection sites.

McSwain said the suit is an amiable first warning of sorts to deter the opening of the site.

“We are not arresting anyone,” he said. “We’re not trying to seize any property or do anything heavy-handed at all. We’re just asking the federal court to look at it.”

But Goldfein said the suit was an expected hurdle and that it won’t deter efforts to open Safehouse later this year as planned, with the support of Mayor Jim Kenney, District Attorney Larry Krasner and former Gov. Ed Rendell.

“We have had a longstanding disagreement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office about the legality of safe-consumption sites. You can disagree with someone only for so long,” she said. “Sometimes there has to be a move forward, and this is that move forward.”

The Safehouse organizers were given 30 days to respond to McSwain’s allegations. From there, the case will be decided by U.S. District Judge Gerald McHugh Jr., a West Philadelphia native who was appointed by President Obama.

“We are hopeful that we will have an opportunity to present our evidence and that it will be heard in a fair and impartial manner,” Goldfein said. “I’m optimistic that we will ultimately be permitted to save people’s lives.”