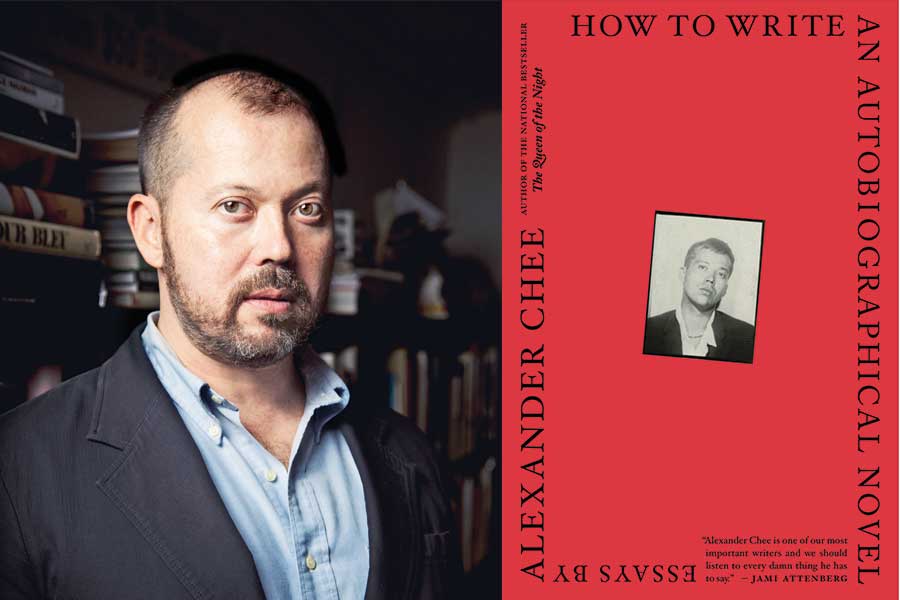

Alexander Chee is an openly gay Korean-American author, teacher and activist. He was a member of ACT UP in the late 1980s-early ’90s and his writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Advocate, OUT and the San Francisco Review of Books. He also penned novels “Edinburgh,” “The Queen of the Night” and, most recently, the essay collection “How To Write An Autobiographical Novel,” which includes stories about his time working with ACT UP and Queer Nation during the AIDS crisis, his first experience in drag and the writing of his semi-autobiographical first novel.

Chee grew up in Maine, lives in New York City and recently visited Philadelphia to read from his new book as part of a collaboration between the literary nonprofit Blue Stoop and Asian Arts Initiative.

We sat down at 30th Street Station for a conversation.

PGN: Do you have any memories of Philly or things about the city that you appreciate?

AC: I have memories of Giovanni’s Room. I remember as a kid going to see the Liberty Bell, having a Philly cheesesteak. I really enjoyed my introduction to Philly’s Chinatown in this visit.

PGN: Giovanni’s Room is a meaningful place for all of us. What do you remember about it?

AC: I remember reading there. It’s hard to explain LGBT bookstores back then. In the kind of acceptance we enjoy now, it’s hard for people to understand the way in which they were these places where you could go to experience a fuller sense of self. So I think it always meant something to me that that place was there.

PGN: Yeah, absolutely. When I was coming out in the early 2000s, I would run into the Oscar Wilde bookshop in New York City and run back to my dorm room.

AC: Right. It’s like taking a little sip of air, and then going back under water.

PGN: My husband was a member of Gay Liberation Front in the 1970s, and it sounds similar to how you’ve described working in ACT UP during the AIDS crisis — that a lot of the minority members had to fight for their space in that group. Gay Liberation Front had contentious nights talking about how they should build on the leverage of Stonewall. But it was a lot of white people. You had splinter groups like Gay Youth and STAR and a lot of discourse that led to great things, but they had to muddle through that.

AC: The sort of basic split that I recall is that the AIDS crisis had radicalized a lot of white gay men who had not been particularly political before then, had not ever aligned themselves with anything other than white male privilege, which is not a community, and also not really an identity; it’s just a kind of status quo. It doesn’t offer any sense of belonging, and the peculiar kind of safety that it offers is one that requires that you don’t examine it, only that you participate in it. So for people like that who have always enjoyed a lot of privilege, there are a lot of skills that they don’t have that you need in the political-movement context. They don’t know how to build consensus because they’re used to being obeyed. They don’t have a sense of how to readjust an argument because they’ve never had to. No one has ever made them. Everyone’s just always been like, “Oh, you’re angry; OK, we’ll make sure that you’re not angry now.” These were the kinds of things we were struggling with then and we’re also struggling with now.

PGN: A lot of the essays in your collection “How To Write An Autobiographical Novel,” and a lot of your work in general, deal with liberating yourself through putting on a mask. And I think a lot of gay people do similar things. They put on a mask and pretend to be straight, and then find it’s hard to drop the disguise. It’s hard to really embrace being out because they spent so long hiding. I wonder if you think young people, with all these resources — do they even need those disguises anymore?

AC: There’s been a certain amount of interrogation of the idea of what coming out means. Coming out is a process. It’s not something that you do once. You do it continually. And every new context that you’re in, there’s always the possibility that someone doesn’t know your identity and maybe they need to know. Early on in my career, I made a decision to be out in my resume, which I used to jokingly call being a professional homosexual. If I didn’t list that I had worked at a gay bookstore or at a gay magazine, it would look like I didn’t have any experience at all, so I really didn’t have any choice, as I saw it. I definitely paid various prices for it. It’s hard to know what, exactly. But I remember a former student of mine who went to work for Esquire, who reported an editorial meeting where he had brought up my name, and the editors said something like, “We really love him, he’s just too gay for us.” So I think people imagine that I’ve had all these kinds of experiences, professional accomplishments, etc., but there are a lot of things I haven’t had. The culture is only now catching up to the place where my work has been since the 1990s. I think there’s a way in which people can experiment with digital identities now, so those are different masks that they’re trying on. Some people also can’t really be in the closet, because they’re too flamboyant or too something else. You never really can hide as much as you think. I used to joke that the person who comes out is always the last to know. But not always. There are always surprises.

PGN: Did anything you learned during the research for your essay collection surprise you? Did you remember the past in a different way?

AC: Yeah. I talk about it in the essay, “The Autobiography of My Novel.” As I say in the essay, the thing that I realized I was doing in my stories was that I was reenacting these dramas from my abuse, where the abuse had taught me to silence myself, to sort of erase the pain that I had felt, and it’s that weird childish illusion that if you stand still, maybe nobody will notice you, maybe you’ll be invisible. That’s just not true. But that paralysis, that frozenness, that standing still as a way to escape being seen was the thing that I had to talk myself out of.

PGN: I think that’s something a lot of gay people — a lot of queer people — go through, too.

AC: And it’s always related to violence — it’s always related to the fears of violence, and I think those fears are as real as ever. We still see people being attacked, we still see people being killed for being queer, being trans. We’re still in this place where we have some rights and protections, but we don’t have full protection under the law. You can still be fired in many states. Now we see the Trump administration actually trying to push that in court, promote that attitude toward us, legally, and that’s very dangerous.

PGN: A lot of the essays deal with trauma and deal with pain. I wonder with any of them, did you ever feel a joy in writing any of the essays? Were any of the essays a joy to write, or were they all difficult in dragging up those experiences?

AC: There’s always pleasure in writing, to a certain extent. The pleasure of figuring something out — which is, you often experience it as relief; you don’t often think of that as pleasure. But I’m wary of people thinking the writing was therapeutic; writing is writing, therapy is therapy. One of the essays is even about how writing alone didn’t save me.

PGN: The reason I ask that question is because I remember you talking about the Asian-American writer Willyce Kim and how she focuses on queer joy over queer pain, and that was one of the reasons you enjoyed her work.

AC: It was. It was interesting to find her novels, so different from what so many were writing back then. It is important to write about the difficulties we’ve faced, to understand them, name them — but then, also, to make room for joy. There’s something about the current age, with social media and algorithms — complaints rouse anger, which creates a feeling of certainty, which can seem comforting in these times, but is also exhausting. And queerness, to me, is always a revolution that begins in pleasures — pleasure as a revolution, even. And I like to remember that.

PGN: And you find joy in people who have been inspired by you, people who have come out from the things you’ve written.

AC: Yes. It is immensely gratifying to get messages from readers who have been helped by the book. That tells me everything I need to know. Whether they are strangers or friends, people who have been able to go into therapy for the first time and talk about things that they’ve never been able to talk about. That’s what I’m in this for. I’ve seen the conversation that not only urges a focus on joy but shades people for writing about queer trauma. And I worry that people will again go into hiding. Because there is a lot of trauma. People are struggling for good reason, and not talking about letting those reasons hide. I’m not writing about trauma to glorify it. I’m writing about it to talk about how I dealt with what happened to me, and how I got through, and to offer people insight into their own lives.

PGN: One of the longtime staffers of [the LGBT bookstore] Gay’s the Word in London was very excited about your collection coming out. He was also excited about “Edinburgh,” your first novel, getting reissued there. Your work does have a worldwide appeal to English speakers and anyone who is queer or struggling with race and identity, and I wonder how that feels, to inspire a person 3,000 miles away in Coventry who happened to pick up your collection and is able to come out after reading it.

AC: I’ve had an international readership of a kind, in a limited way, so this will hopefully expand that. I did an interview on BBC Radio recently, and the interviewer essentially asked how my Korean-American identity was going to matter to an international readership. In other words, Why should we care about you? And I thought it was an interesting question to have to face down. You just don’t know who’s going to get it and who’s not. At least at the end of the interview, he said that the interview had made him a fan.

PGN: People have different essays in the collection that are their favorite. Maybe it’s an unfair question, but do you have one that resonates with you that you enjoy talking about more?

AC: I think I’m most proud of “The Guardians” because it was the hardest to write. I really enjoy reading aloud from “Girl.” That’s one of the most pleasurable essays. Being proud of an essay isn’t the same as it being a favorite. I don’t know if I have enough distance from the collection yet to say which one’s my favorite.