Long-term survivors of HIV face unique challenges – they are the “hidden” survivors of the epidemic. When I was diagnosed with HIV in 1989, I wasn’t sure I’d be here in 2018 to talk about it.

At the time, there was no effective treatment for people living with HIV; it was basically a death sentence. For those of us who did have access to healthcare and treatment, we were given what we now know is suboptimal therapy that not only rendered us resistant to more effective medications that were being developed, but also had life-altering side effects that remain with some of us to this day. These side effects from those earlier, more-toxic treatments have added to the stigma of aging with HIV and have disfigured us, made us frailer, and caused our hearts to literally skip a beat.

Don’t get me wrong — I am grateful to be here. As a white, gay, cis man living with HIV who turns 60 this year, I also recognize and acknowledge my privilege. I have access today to a one-pill, once-a-day therapy that keeps my virus fully suppressed so that I’m unable to pass on HIV to others, and I experience virtually no side effects. But I also know that when I walk into a room, I have “the look” — the sunken cheeks, the veiny arms and legs, the extended belly. “You should be grateful to be here,” we’ve been told, “thankful to be alive!” But to what end? Grateful to be here to suddenly be rolled off of disability after being out of work for 20-30 years, expected to join the ranks of the work force without any specialized training or support? Grateful to be here only to fall into addiction or isolation because our support networks, friends and former lovers no longer exist? Grateful to be here while there is scant culturally competent care for aging LGBTQ+ seniors who are living with HIV? We as a society in general do not value our elders – how does the LGBTQ+ community regard those of us aging, let alone aging with HIV?

There is much work to be done, but if anyone can lead the way, it’s people living with HIV and our allies. We were the ones who took care of each other back at the start of the epidemic, and we will come to the forefront of the battle once again. The lesbian community was there for many gay men back in the 1980s when we were dropping like flies and no one else would touch us; thank heavens for these unsung heroes. Community-based organizations like TPAN were founded by people living with HIV so that we could survive and thrive. Informational resources like “Positively Aware” delivered the information we needed to live healthy, happy lives.

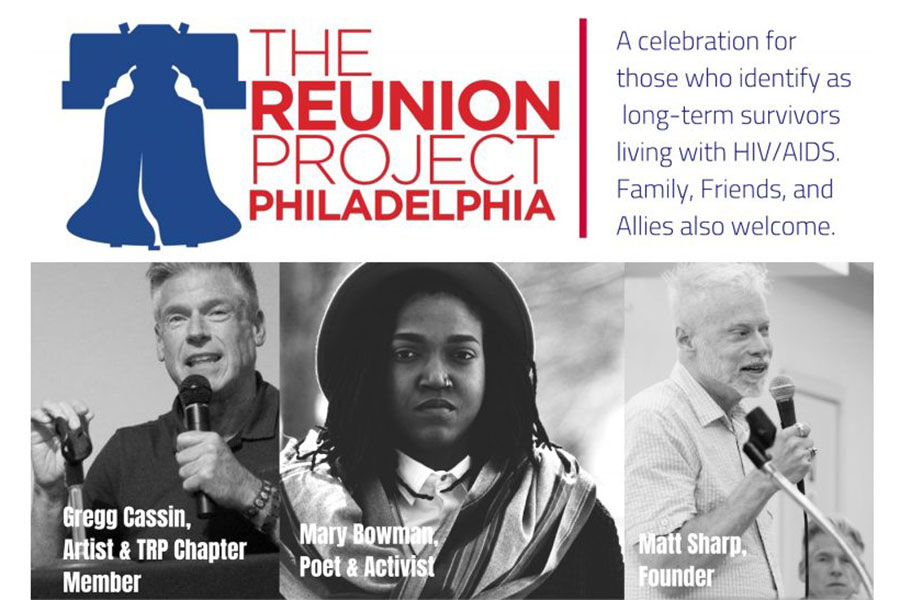

Earlier this year, The Reunion Project convened a community-led, diverse coalition of survivor advocates to discuss the needs and priorities of survivors and issued a report in June. Go to tpan.com/reunion-project for more info. As someone living with HIV for 29 years, I am excited to be part of a national network of survivors that is giving voice to those who don’t have one and who have in many respects been left behind.

Currently, 50 percent of people living with HIV are over age 50, and by 2020 it will be 70 percent. But we knew this was coming. Where is the sense of urgency? Where is the crisis task force taking up our agenda? Do we matter?

I believe we do. As the saying goes, with age comes wisdom. Long-term survivors have an opportunity to come together and join forces, mentor those coming up behind us on how to age and live with HIV gracefully and to advocate for those who have no voice. An entire generation was lost, so who now is going to step up and advocate for us?

Those of us who have survived.

Jeff Berry is the editor in chief of Positively Aware magazine, and director of Publications at Test Positive Aware Network in Chicago. Find him on Twitter @PAEditor.