Garrard Conley’s poignant memoir “Boy Erased,” about his experiences undergoing gay-conversion therapy, is appearing on the big screen, adapted by writer, director and actor Joel Edgerton.

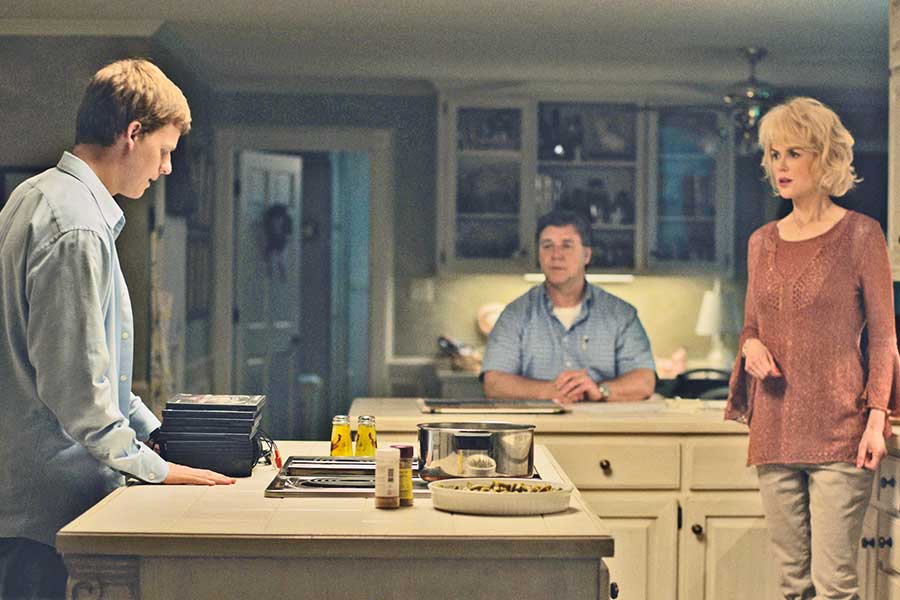

Edgerton’s adaptation alters the source material in several respects, but it still focuses on Jared (Lucas Hedges), whose Baptist-preacher father Marshall (Russell Crowe) and steel-magnolia mama, Nancy (Nicole Kidman) send him to a program (called “Love in Action” in the book) to “cure” him of his homosexuality. The benevolent film shows how Jared and other teens fare in the program run by Victor Sykes (Edgerton), whose methods consist of verbal and physical abuse.

“Boy Erased” addresses the issues surrounding, and the motivations for, gay-conversion therapy. Edgerton, who met with PGN during the recent Philadelphia Film Festival, aims his story at parents who need to be educated about this nefarious practice. The filmmaker acknowledged the role his own parents played in his early life, calling them “everything to me” and “my source of information and my protectors.”

“The thought of having those two people telling me not only that there was something wrong with me, but that I was no longer welcome in their family if I weren’t willing to change something that was out of my control — I don’t know how much damage that would cause me, and how easy that would be to forget.”

The director researched gay-conversion therapy before reading Garrard Conley’s book. “I’d heard trace elements, and my response had always been, ‘Are you fucking kidding?’ It’s one of those things that was surprising, but yet it made sense. In Australia, in the early ’70s, homosexuality was considered a mental illness. In the wake of that opinion changing, on a government- policy level, it created this open space for the church to have to do something. They couldn’t chuck people in an institution anymore. I knew conversion therapy was born out of that time. I heard about tortuous practices and the pushing and misappropriation of other therapies and ideologies.”

Reading Conley’s memoir certainly struck a nerve with the filmmaker. He had been thinking about marriage equality after making the film “Loving” (2016), about the landmark 1967 case in America concerning interracial marriage. His interest in institutions prompted him to read “Boy Erased.”

“I had this deeply emotional response to Garrard’s story that I could easily judge as absurd. But knowing that it really happened — and it was still happening — it felt like something needed to be done about it,” he recalled. “The project picked me.”

Edgerton soon met Conley, who became involved in many aspects of the production, including reading drafts, seeing edits of the film and even being on set. The filmmaker met with John Smid, the former director of Love in Action and the basis for the character of Victor Sykes in “Boy Erased.” Edgerton also went to church with Conley’s parents and visited Dr. Julie, played by out gay actress Cherry Jones in the film. Suddenly, he was deeply,

creatively involved.

The filmmaker acknowledged that his approach to the sensitive material was to follow Conley’s voice in the book.

“In his beautiful, empathetic nature, Garrard understood that everybody was, in their own discombobulated way, trying to help. They just had the wrong information. They had beliefs that put them on a certain side in terms of where homosexuality comes from. In their mind, it came from a behavioral, sinful place. That doesn’t make them bad people. The best way for us to help other people understand and dismantle conversion therapy is to be empathetic to that point of view so people can judge it for themselves. Victor Sykes and the parents in the movie are not meant to be out-and-out villains, just other human beings with the opposite point of view.”

That said, there are some changes Edgerton made from the book, which is more of an internal, confessional story. The memoir features symbolic baptisms, as well as themes of erasure and purification that are absent from the film. Edgerton bemoans the scenes he had to leave out, saying, “It’s a case of killing your darlings. There is so much in the book that I find interesting. Behaviors Garrard had that were born out of frustration — like peeing in a bottle or on a carpet or emaciating himself. We shot a scene of thoughts of suicide and attempted suicide. S, who is Sarah (Jesse LaTourette) in the film — I actively took out her situation [in the book] and created a different narrative for her because I don’t want anyone to think that we are representing any of these people in the therapy as deviants. Because that’s what Love in Action did.

“Other alterations include the character of Cameron. I did that with the approval of Garrard. I told John Smid, when I went to meet him, that I was depicting the fake funeral. In the book, there is a page where Garrard talks about holding a fake funeral for a boy — and that boy is still alive. He went through a six-hour exorcism. If you look online about gay-conversion exorcism, they are long, drawn-out physical- and verbal-abuse practices to exorcise the demon of homosexuality. I didn’t feel that that was dishonest. I wanted to include that page and include the story of Cameron as far as I did because of the [reaction kids had] to conversion therapy.”

But the strongest elements of “Boy Erased” are not the harsh scenes of “therapy” — like the slow-motion scene of Cameron being beaten — which can feel manipulative, but the bond that develops between mother and son. A running mama-knows-best joke in the film has Nancy warning her son not to stick his hand out a moving car window, as Jared defiantly does.

Edgerton emphasized the mother-son relationship because “Nancy was his chaperone to [therapy]. She had a chance, outside of the shadow of the father, to really tune into what was going on with him.” Kidman gets a terrific monologue near the film’s end that will generate cheers from viewers.

As for Garrard’s father, Edgerton renders Crowe’s character as someone who is trying and still evolving. “I hope — not that it’s my place — but I hope the film changes [Garrard’s father] Hershel’s mind.”

And speaking of hope, “Boy Erased” does offer encouragement for Jared. Edgerton may have been interested in what he described as “the dark suppression of sexuality and how dysfunctionality in individuals can lead to the abuse of others.” But Jared’s non-sexual romance with Xavier (Théodore Pellerin) provides what the filmmaker called “a ray of shining light of honesty and tenderness. I wanted the almost-entire film to be the story of what one boy went through to get to a place where he could finally have a sexual life that was honest and true to himself.” n

“Boy Erased” opens Nov. 9 at the Landmark Ritz East. 125 S. 2nd St.