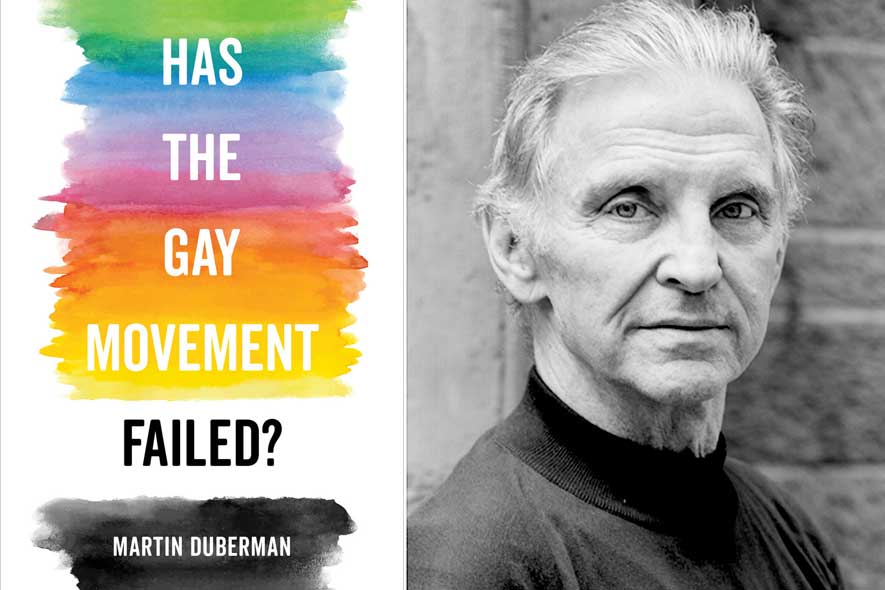

Martin Duberman aims to shake the LGBT community’s complacency with this polemical book, “Has the Gay Movement Failed?”

Duberman outlines his case for why marriage equality and the right to serve openly in the military represent paltry gains given the right’s eagerness to pass bathroom bills and religious-liberty laws.

Duberman’s judgment may be harsh, but it isn’t easily dismissed. A distinguished historian and prolific author, he’s written more than 25 books, including “Cures: A Gay Man’s Odyssey.” An outspoken activist, he also founded CUNY’s Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies in 1991.

In recent years, Duberman was surprised by the overly confident tone of books such as Linda Hirshman’s “Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution.” Curious to see how it compared to firsthand accounts of the early gay movement, he reread Karla Jay and Allen Young’s 1972 anthology, “Out of the Closets: Voices of Gay Liberation.” Many of its contributors were active in the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a small, radical group that flourished briefly.

The GLF stood in stark contrast to the homophile movement that preceded it: “Vociferous and demanding, GLF announced the advent of a new kind of queer: boisterous, uncompromising, hell-raising,” he writes.

It’s precisely those qualities, he believes, that are sorely lacking in today’s LGBT rights movement, which he describes as mainstream, centrist and shortsighted. “Its tactics, goals and ambitions are simply those of a typical ethnic group, hell-bent on getting inside the machine and careful not to throw even a small wrench in the gears.”

In contrast, the GLF called for a full-fledged assault on all deeply entrenched, systemic flaws. “GLF’s concerns went considerably beyond gay issues themselves,” Duberman notes. Equally important, the GLF viewed sexual pleasure as intrinsic to genuine freedom.

The writer asks the question: How did marriage, an institution vilified by the GLF, become the principal focus of the mainstream LGBT movement for the past two decades?

Certainly, the AIDS crisis factors into it, but the answer, Duberman suggests, is much simpler: The majority of people, including LGBT people, simply want to fit in. As he puts it, marriage “landed on the top because that’s where the majority of gay Americans want it to be.”

As Duberman points out, most LGBT people are working class, though you’d hardly recognize that from the agenda of mainstream LGBT groups like the HRC. “What’s objectionable about the Human Rights Campaign,” he argues, “is not that it works to achieve full protection and citizenship for gay people, but that it seems to care a lot more about those already privileged than about those suffering at a basic level from economic deprivation.”

Besides, even if the institution of marriage benefitted by incorporating positive elements of LGBT relationships, which Duberman regards as being more egalitarian, emotionally expressive and sexually adventurous than hetero ones, there’s an intractable impediment: straight white men. That demographic has strenuously resisted any threat to its privileges, and continues, in his opinion, to find the mere idea of gay sex abhorrent.

So what is to be done? First, Duberman advocates abandoning single-issue politics. Instead, the LGBT movement must adopt an intersectional agenda focused on basic economic rights. Second, it will have to make alliances with other leftist organizations, even when those groups don’t wholeheartedly embrace their LGBT allies.

The stakes are simply too high. “The amount of suffering in this country, when compared to its resources, is iniquitous,” Duberman writes. “If we are ever to reduce it, we must combine with allies who we don’t love but who share with us a common enemy — the country’s oligarchic structure, its patriarchal authority, its primitively fundamentalist moral values.”