Willyce Kim is the first Asian-American lesbian writer to be published in the U.S. She spent her childhood years in Hawaii and California before graduating from San Francisco College for Women in 1968. Kim was influenced by musicians such as Bob Dylan and Joan Baez and writers including Adrienne Rich and Diane Di Prima. She self-published her first poetry chapbook, “Curtains of Light,” with her sister in 1970 and soon after she began working with the Women’s Press Collective in Oakland. As a member of the collective, she published works, took photographs, and traveled the country to distribute literature and give readings at colleges, bookstores and women’s bars. In the ’70s and ’80s, she published three poetry collections, two novels, and contributed to literary magazines including The Furies, Phoenix Rising, and Conditions.

“She celebrated lesbian life and lesbian love,” said poet and artist Kitty Tsui, who met Kim in the late ’70s and co-founded the Asian women’s writers collective Unbound Feet. “She used to read in the Bay Area with Pat Parker and Judy Grahn. They did a lot of poetry readings, and that’s when I became familiar with her work. When I came out in the 1970s I came into a community of all white women. She was the first Asian-American lesbian that I saw in the flesh, so she really was a great role model for me because I thought I was the only one.”

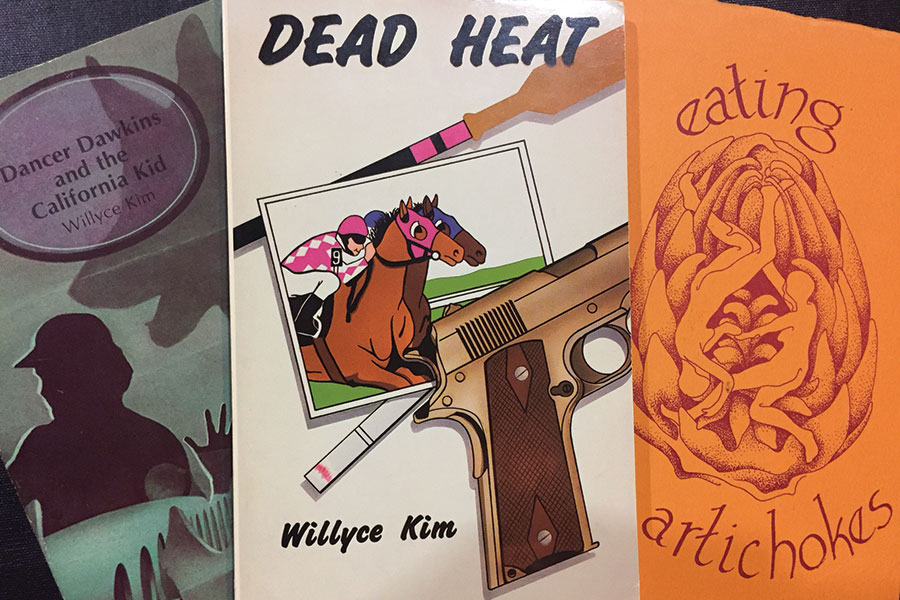

Kim’s writing deals with female empowerment, friendship, and family, and she handles sexuality — often pairing it alongside food metaphors — with sensuality and humor. In a scene from her 1985 swashbuckling novel “Dancer Dawkins and the California Kid,” Dancer Dawkins eats ice cream and the shop clerk compares her flavor euphoria to having an orgasm. The title poem in the collection Eating Artichokes, published by the Women’s Press Collective in 1972, closes with the line “your entire artichoke can become a very heavy sexual fantasy.” Kim also addresses issues of women’s liberation, specifically Asian-women’s liberation, human trafficking and colonialism in her work. Her characters unabashedly stand up for themselves and the people they care about.

The prose in her novels consists of short vignettes — some only a paragraph long — that build on one another. Publishers Weekly, in a review of Kim’s second novel, Dead Heat, wrote: “Kim’s lean, deadpan style belies her gift for seeing subtle humor in the ordinary, shambling state of human nature. Her characteristic technique of breaking down the plot into brief scenes successfully conveys the sense that aimless events are converging into a mosaic of meaning, independent of the efforts of her anti-heroines and perhaps far beyond their ken.”

Kim, along with the members of the Women’s Press Collective, published works about lesbian women at a time when it was not socially acceptable and often dangerous in many parts of the country. After enduring Catholic schools in her childhood, she went to college near the Haight-Ashbury in 1964, two years before Compton’s Cafeteria Riot and five years before Stonewall. At the time of her first two book publications, the American Psychiatric Association still considered homosexuality a mental illness. Organizations such as the Women’s Press Collective were safe spaces for voices like Kim’s, and through their publishing and activism they encouraged women of all races, economic classes and sexualities to live their own way. In a 1985 review of her first novel, Feminist Bookstore News wrote: “Kim’s writing makes clear the difference between merely describing lesbian relationships and delighting in them.”

In addition to writing, Kim did printing and teaching jobs, and for several decades worked as a supervisor at the University of California at Berkeley library. Her works have influenced the likes of author Dorothy Allison, poet Pat Parker and the novelist Alexander Chee, who wrote: “She helped found a press based in a community of feminists, she took photos of them, she wrote about them and herself — she’s an inspiration. I think her decision to write high-spirited adventure novels about lesbians is perhaps a part of that same off-handed freedom she seems to have cultivated, and I love that. In today’s context, we would call that focusing on queer joy over queer pain, and maybe that’s her lesson for us.”