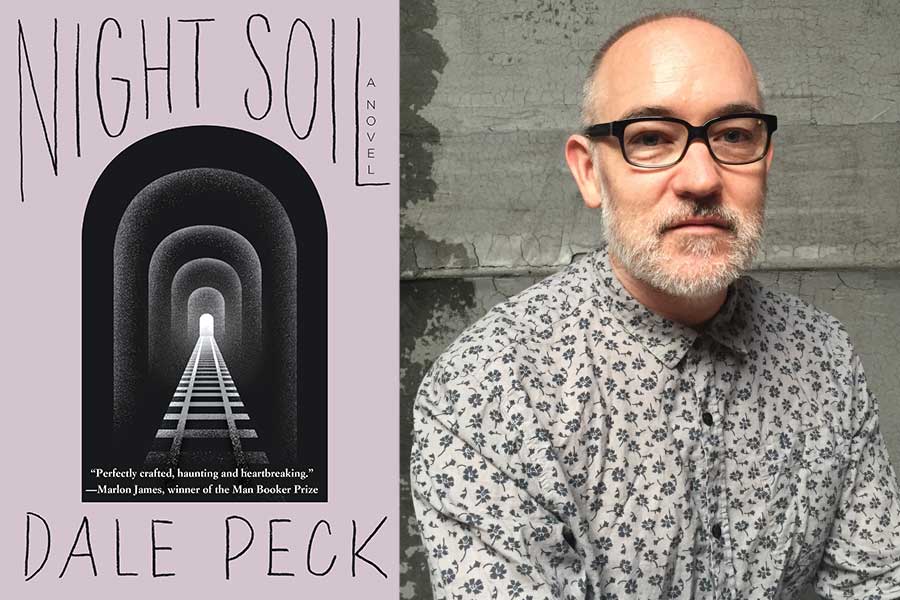

Out gay author Dale Peck’s debut novel “Martin and John,” came out 25 years ago and helped establish him as a writer of note. Meanwhile, his latest novel, “Night Soil,” has just been published and it’s a testament to Peck’s literary talents.

The book, a dense read, is narrated by Judas, the 17-year-old gay son of a famous potter, Dixie Stammers. Judas tells the story of his life and his extended family in an almost-confessional tone.

Reading “Night Soil” can feel like one is being told some deep, dark secrets — and, given the family skeletons as well as Judas’ anonymous sexual exploits — that is an apt categorization. This quality certainly adds to the book’s appeal.

However, the author frequently overwrites, and some of the prose is particularly challenging. In one passage, Judas catalogues numerous toilet articles, including his mother’s various douching products — “more varieties than there are, as far as I know, of vaginas, let alone vaginal irritation,” Judas explains. There are several pages describing terraced houses in great architectural detail. Peck alphabetically lists 66 different trees, then teases readers with species and cultivars. Later in the book, the author literally spends five pages describing Judas’ masturbatory habits.

He also goes as far as to include visuals to illustrate the “twenty-five-foot-wide vortex” and “Flemish bond” patterns Judas creates with the inheritance of his father’s books — approximately 15,000 titles, forming 314 stacks, each 7-feet tall.

The author will prompt even learned readers to frequently consult a dictionary to look up some of the more obscure words he uses. Since Peck likes lists, here are some of the fancier words he employs: “fastigiate,” “vitiligo,” “pleached,” “fugacious,” “palanquin,” “phragmites,” “amphorae,” “elenctic,” and “eidetic.”

Together, all of these elements are almost enough to make readers throw the book across the room rather than actually read it. But to Peck’s credit, there are vivid images of Judas washing his mother’s smock, dousing it in lye, and the teenager’s fascination with his elaborate birthmark that covers half his body, making much of his skin purple. A description of harvesting clay in a garden is also fascinating.

Peck employs some really nifty similies, such as “the pine trees seem to crowd each other like a concert audience,” or when Judas says the frame of the door “fell into my arms like an anorexic cheerleader.” Judas is described as “working with the patience of a philatelist” to shimmy a door loose. There is also an impressive passage where Judas, about to describe an engraved photograph, wonders whether he should “start with the horror and move on to the banality, or open with the bucolia, then blindside you with the brutality.”

“Night Soil” does reward the patient reader who may struggle through the first half of the book. In the early chapters, Judas provides lengthy descriptions of the Academy, a private boys’ school founded by his great-great-great-great-great grandfather, a coal magnate, along with a detailed discussion of his mother Dixie’s handmade pots, which are notable for each being as perfectly round as a cannonball. There is not much plot, but plenty of background from Dixie’s missing twin brother, Guy, who disappeared when she was 13, to Judas’ father’s uncle Anthony, who leaves the teenager an inheritance.

The plot kicks in around the same time the queer content appears — about halfway through the story. Judas starts frequenting State Comfort Station NE-28. It is here in a rest stop “that had slipped from local consciousness” that Judas takes in the overpowering stench of shit and, after reading the creative graffiti, discovers the toilet’s glory holes and positions himself to be penetrated both orally and anally at the same time, like a pig on a spit. Peck’s descriptions are quite graphic, but they engage because they are so lurid. Judas soon becomes enamored with a student at the Academy and has an erotic sexual relationship with him in the crypts of the Academy and beyond.

Judas also does some research into the family history and makes startling discoveries, which eventually lead to the conclusion of the central narrative that is appropriate, and even emotional.

“Night Soil” also includes a 35-page coda, entitled, “Parable of the Man Lost in the Snow,” a lesson that students at the Academy endure — there is really no other word for it — to teach them critical thinking. Some readers may appreciate this section of the novel, and it may very well be a parable for Judas’ story. But anyone already exasperated with Peck’s book will want to skip this chapter, which gets philosophical and psychological beyond anything in the previous 200-plus pages.

Peck seems to be daring readers with his taxing novel. It is not without merit, but it does require considerable effort.