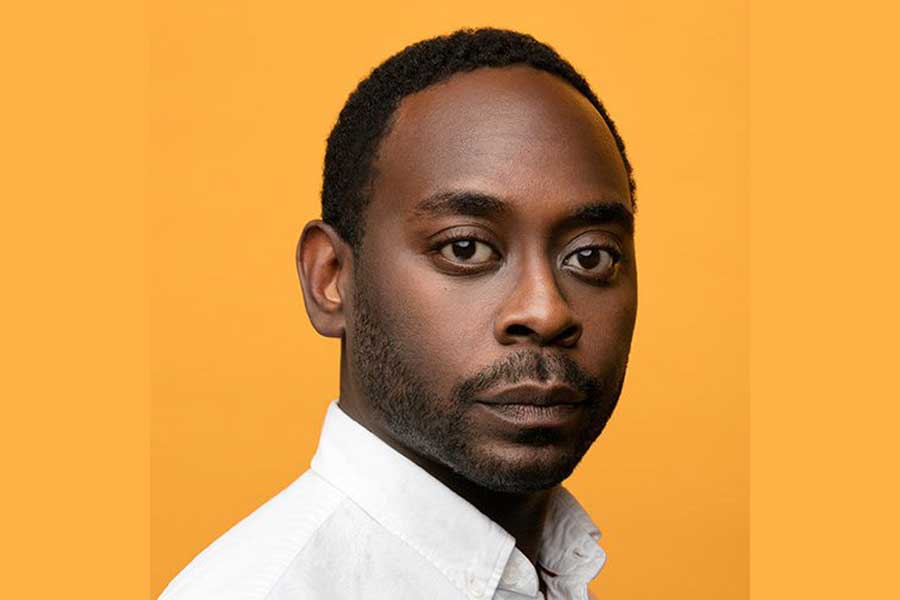

Whether as a playwright, a performer-actor or a producer with the recently late, great Orbiter 3 company, South Philadelphia’s James Ijames seems incapable of making bad decisions or wrong-headed moves.

Forget about awards such as an F. Otto Haas for Emerging Artist, two Barrymores for Outstanding Supporting Actor (“Superior Donuts,” “Angels in America”) and one Barrymore for Direction (“The Brothers Size” with Simpatico Theatre Company), to say nothing of a few Pew Fellows. James is an insightful, inventive creative — a proud gay black man whose work seems to insistently blossom anew, even when tackling work he’s essayed in the past or plays that examine the American before-and-after.

Take “Kill Move Paradise,” currently opening in preview at the Wilma Theatre for its Sept. 4-23 run as part of the 2018 Philadelphia Fringe Festival, after having had its world premiere with the National Black Theatre in Harlem.

Ripped from the headlines of what Ijames calls “the contemporary myth that all lives matter, the expressionistic “Kill Move Paradise” looks at four young African-American males’ earthly existences quickly cut short, and a play’s time in which they must remember how they lived and died — some because they were black like Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland and Sam DuBose.

The four characters work within the framework of external narratives and the outward signs of stereotypes placed on them. Rather than be tied down by plots, “Kill” operates on a transcendental plane, a place where “physical and spiritual transformation” takes place, “activated through their healing of one another,” Ijames said.

As an artist with a self-proclaimed obsession with “the American experiment” (“how we can use art to expose how imperfect this place is, in an effort to make it more perfect”), a ready preoccupation with “inheritance and legacy… a building of a new kind of legacy” and in Paula Vogel’s words, “to make the familiar strange and the strange familiar,” Ijames brings the ardor of police brutality and a personal, yet existential, disgust with the existing power structure to the proceedings.

“It’s personal to me because it’s probably the angriest I’ve ever been in my writing, and it exposes my own anxiety,” he said. “About death, about being black in America. But I guess most of my plays are personal when you get down to it. right?”

The subject matter of “Kill Move Paradise” is all around us, he said, whether it’s black men and women being killed by law enforcement or trans women being killed or the many other ways marginalized people are victims of systemic racism, patriarchy and misogyny.

“The characters have some parallels to real people, but are wholly my invention. In some ways they are versions of me. I wanted the title to be reminiscent of a video-game title, because they invoke both a kind of exhilarating euphoria and a desensitization to violence and brutality.”

Everything that he writes and performs must reflect the African-American Ijames, the gay Ijames, the male Ijames, even the Philadelphia Ijames. “All of those notions are present in my work. I don’t think I sit down to write and think, How can I expresses every corner of who I am in this scene? That’s strange. I think who you are naturally finds its way into what you make.”

Since the play’s original conception and inception, things have changed, some far more dramatic and life-altering than others. Ijames noted that since the first mounting of “Kill Move Paradise,” there is a larger slate of victims; people who have been killed, either by police violence or vigilantes.

“That list has grown since I first wrote the play almost four years ago,” he said. “We have also done some work on the script to make the play stronger. You learn a lot about the play in rehearsal and with new actors and new directors. So it’s a chance to really get the play to a place that feels good.”

The newest director, Wilma’s Blanka Ziska, is a true collaborator in bringing this “Kill Move Paradise” to Philadelphia stages. “

I really love working with Blanka and trust her completely. Her approach to the work both with design and in the room with the actors is exciting and daring. I’ve never really seen anything like it. It’s a true collaboration. She’s an incredible interpreter of plays, and I’m really thrilled that she’s working on mine,” said Ijames.

When it comes to the necessary activism in the foundation of “Kill Move Paradise” like shale and sand, Ijames doesn’t picket or protest. He puts his money where his mouth is.

“Activism for me is in the daily small acts of radical compassion, empathy and disturbance. How I choose to spend my money and time. The ideas I expose my students to, so their learning isn’t limited but is inclusive and expansive. And I try to write in such a way that provokes change. I’m going to be doing artEquity facilitator training this fall so that I can be a voice of diversity and inclusion in the region and in our theater community.”

The writing that provokes change:

No one sets out to purposely create controversy or stir a pot, but knowing what I know about his work in the past and the tone of this play, it is certainly provocative.

“I think provocation and controversy are different things. I am certainly interested in provoking people to think, to action, to empathy in all of my plays. I actually don’t think the play is all that controversial. It’s in the same world as like Sartre’s “No Exit” or — and I’m not comparing myself to this writer — Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot.” And of course I’m sensitive to what’s in the world around me and that will find its way into my work. I like to escape too. We can have both. This play has both escapism and difficult provocation for an audience.”