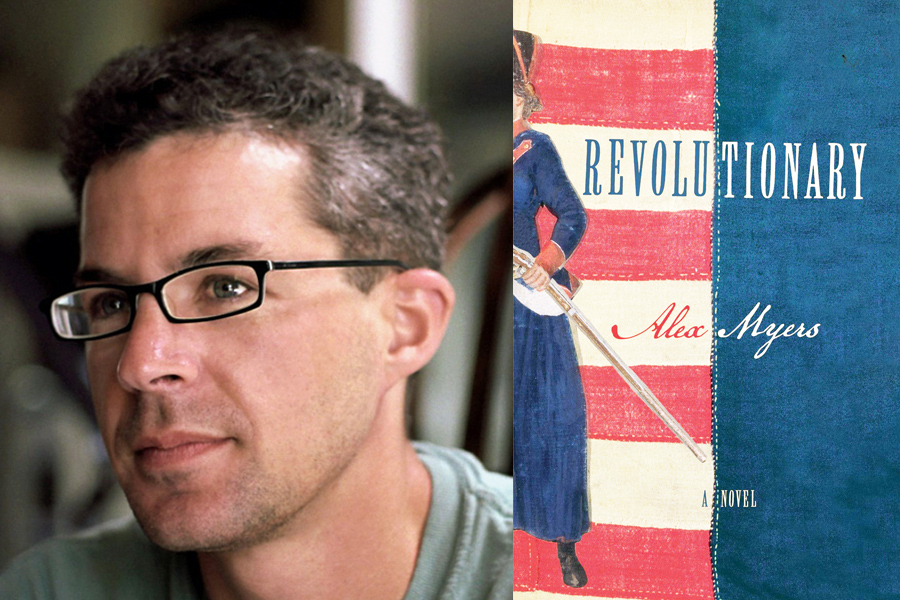

In celebration of Women’s History Month, the Museum of the American Revolution will welcome transgender author Alex Myers (born “Alice”) to its History After Hours series March 6 with an event entitled, “Fierce Females.” Myers penned the 2014 novel “Revolutionary,” based on his real-life ancestor Deborah Sampson Gannett, who dressed as a strapping male soldier to fight in the Revolutionary War.

The author spoke with PGN about mixing fact and fiction to create his novel.

PGN: What is your understanding of the night you will be part of — “Fierce Females” — and Philadelphia’s newest museum?

AM: Females in general, let alone the fierce ones, often get ignored in the Revolutionary period. We focus on the other FF, the founding fathers. I’m looking to counter-balance that narrative. And that is part of what I think the museum is about: telling a story that we think we all know. The stories of women from the American Revolution are sometimes condensed down to Molly Pitcher and Abigail Adams — a lot of stories of women as supporters, helpers. These stories keep the women in their proper spheres: wives, mothers, etc. The truth is that women fought on the battlefield with men all the time in the war. Molly Pitcher was loading a cannon when she was shot. These women were fierce! But we hear instead about how she carried water for the men and don’t really stop to wonder why she was on the battlefield in the first place.

PGN: Do you believe you would have been so deeply entrenched in her transformative story and that history in general if you had not been born “Alice”?

AM: Probably not. Her story really spoke to me and still does. It is so like, and unlike, my own journey. I heard her story from my grandmother when I was a little girl. I remember thinking that I wanted to be like Deborah — that I understood her and that she would have understood me. I can recall thinking about what her life must have been like, and wondering whether other people had done things like that. As a kid, I was desperate for role models of women who had anything near an identity like mine. They were few and far between.

PGN: Please tell me about the idea of fictionalizing her story. I love exploded reality but it blurs what is and what isn’t.

AM: With Deborah, I dove in to the facts of her life and found that there wasn’t a lot that was verifiable. She tells us what she did in a memoir, but a lot of this is clearly made up. When I researched her and realized that so much of her story was unknown, or unable to be corroborated, I decided to make the “skeleton” of the novel out of the facts that could be substantiated and then embellish on my own. So, for example, she claims she enlisted earlier than we can verify, so I took a later date of enlistment, which matched all the documentation I could find. Once we presume her membership in a unit, we can track some of that company’s movements. This gave me a sort of skeleton for the piece. From there, I looked at where the holes were. The accounts are often very vague: “The company rotated through duty along the Hudson” would be a typical report. I could really make up almost anything I wanted. So I read a lot of history books and whatever I could find on the period, and had fun imagining what it was like for her, trying to keep within the bounds of the possible.

PGN: Are the differences between the truth and the fiction so radically different?

AM: I’d offer the example of Deborah’s own memoir. It is more fictional than my novel. We tell the story we want to tell and call it fact or fiction depending on our era [or] our motive. But I am a thorough subscriber to Tim O’Brien’s idea of a “true” story and “story truth.” With Deborah, I really believed that she wanted to live as a man. That was the truth. Now, how to tell a story that would portray that truth? Fiction was necessary. It wasn’t appropriate for her to speak desires such as these in her time period. So I had to invent and work around her constraints.

PGN: What do you know/what have you gathered about Sampson’s true transgender nature?

AM: Nothing I can support with fact. I have only my own best guesses. For me, the most profound “evidence” is that after she came back from the war, she lived with a relative — an aunt, most likely — and told people she was Ephraim, her brother. The fact that she tried to continue passing as a man suggests to me that she preferred to live as a man, but wasn’t able to make it work due to social and monetary constraints. It seems she wanted the money, perhaps the adventure and, I think, the chance to be a man. It is impossible to say what she wanted … she doesn’t tell us that in so many words. Researching her life, I imagine it was impoverished, routine, constrained and rather bleak. I do think money was a huge motive. But I also think that she enjoyed living as a man, and felt that it fit her personality.

History After Hours: Fierce Females will take place 5-8 p.m. March 6 at the Museum of the American Revolution, 101 S. Third St. Visit http://bit.ly/2F8HJNz for more information.