In 1996, Cheryl Dunye broke queer-cinema ground with “The Watermelon Woman.” She was the first out African-American-lesbian filmmaker to direct — as well as write, edit and star in — a feature film.

This scrappy little landmark of independent queer cinema, set and shot in Philadelphia, will screen at the Lightbox Film Center (formerly International House) 7 p.m. Feb. 21. The event is free with a reservation.

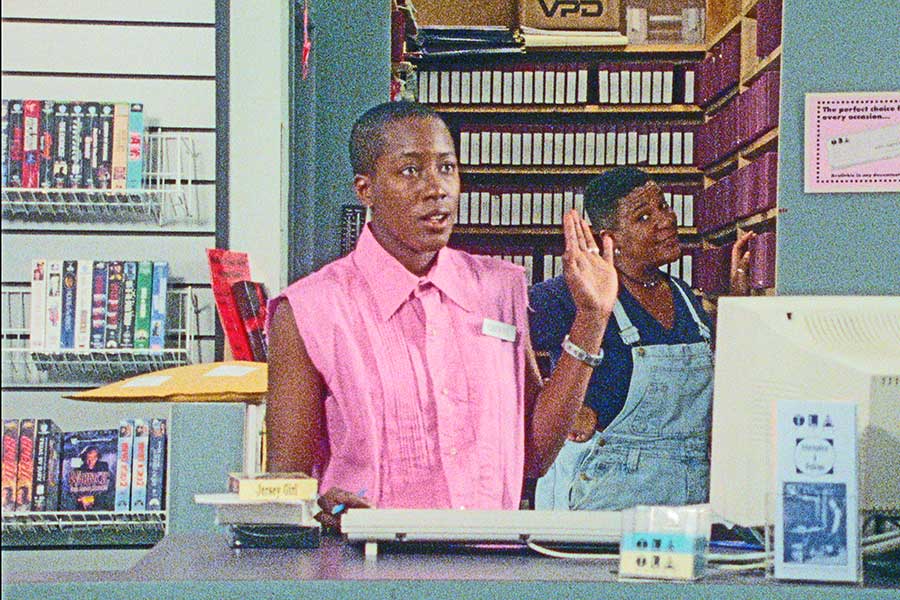

Duyne stars as Cheryl, a video-store clerk and budding filmmaker, who is fascinated by the (fictional) African-American actress Fae “The Watermelon Woman” Richards (Lisa Marie Bronson) after seeing her play a mammy role in the 1930s film “Plantation Memories.” Cheryl starts a video-documentary project investigating Fae’s history because “black women’s stories have not been told.” In the process, she makes startling discoveries about Fae’s life, work and relationships — as well as her own.

“The Watermelon Woman” is a fun and provocative episodic film. The loosely structured narrative creates multiple layers of meaning as Dunye incorporates photographs, archival-film footage, wedding and performance videos, on-the-street interviews (look fast for PGN’s Suzi Nash) and a film-within-a-film. She shoots on location throughout Philadelphia, setting scenes inside TLA video and the Free Library, as well as outside the Ritz Theater and the Philadelphia Museum of Art to create what Dunye calls “urban realism” in her film. (There is also an affectionate shout-out to queer bookstore Giovanni’s Room.) Other scenes are set in Bryn Mawr, Rittenhouse Square, South Philly, Swarthmore and Wynnewood.

On screen, Dunye is ingratiating whether she’s talking in direct address to the camera, or dancing on a rooftop with the city skyline in the background. Her camaraderie with her best friend Tamara (a scene-stealing Valaria Walker) is infectious. Dunye nicely depicts the way best friends behave, as when Tamara tries to set up Cheryl on blind dates, with little success. But she also shows how besties get on each other’s nerves: Cheryl’s obsession with her project splinters their friendship.

Likewise, Cheryl’s relationship with Diana (Guinevere Turner), a white customer at the video store who becomes her lover, is also compelling. The women generate considerable sexual tension in their conversations and plenty of heat in the sex scenes.

However, “The Watermelon Woman” is about more than just representing African-American lesbian experiences on screen. The film’s theme is history, both African-American and/or queer.

In one sequence, Cheryl meets with Lee Edwards (Brian Freeman), a gay man who talks about the heyday of the black-owned and operated theaters in 1920s and ’30s Philadelphia: the Royal, the Dunbar and the Standard. She interviews out academic Camille Paglia, who offers an analysis of portrayals of race, gender and sexuality in culture. And in an amusing scene, Cheryl and her colleague Annie (Shelley Oliver) visit C.L.I.T., the Center for Lesbian Information and Technology, where an archivist (out writer Sarah Schulman) effuses about the collection and admonishes Cheryl for filming the materials.

The film also includes a notable sequence where Cheryl has an unpleasant encounter with the police, who erroneously think she is both male and a thief.

It may seem as if Dunye is cramming too many stories and visual styles into her film, but the various narratives and approaches connect and assemble. When Cheryl discovers that Fae had an interracial romance — back in an era when such relationships were taboo — it mirrors her affair with Diana. Likewise, when Cheryl interviews her mother (played by her own mother, Irene) about Fae, she has little memory of “The Watermelon Woman.”

In contrast, other interviewees can recall exact details that led Cheryl down another rabbit hole. Moreover, when a librarian (the late, great gay writer David Rakoff) is unhelpful providing materials on Fae, other sources contain a treasure trove of images and information. Dunye’s point, which comes across beautifully, is that sometimes we have to search deeper into our own history, and sometimes we have to create it ourselves.

And sometimes — as is the case when Cheryl confronts a woman who denies Fae’s lesbianism — you have to scare folks with the truth.

Dunye’s film is, as she says, ultimately about inspiration, hope and possibility. The filmmaker creates all three with “The Watermelon Woman.” Dunye has paved the way for positive African-American lesbian representation. Her film may be more than two decades old, but it is still significant and highly satisfying.

Just as Cheryl looks to the past to understand her present, audiences should watch (or rewatch) “The Watermelon Woman” to look back at where we were and how far we — as well as Dunye and her cast — have come since her groundbreaking film.