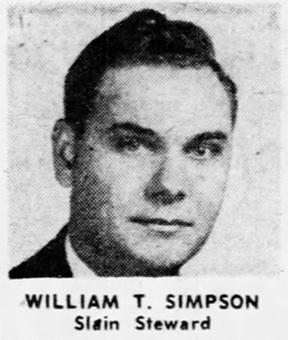

The “Homosexual Panic” that started in the 1950s can be traced back to one event — the murder of Eastern Airlines flight attendant William T. Simpson in August of 1954.

Maybe more importantly wasn’t the murder itself, but how Miami Daily News reporter Milt Sosin covered the tragedy.

The Man: A gay flight attendant

Like most gays at the time, Simpson lived a pretty modest life. He was 27 and among many gay men who worked for Eastern Airlines as a flight attendant. Eastern Airlines was based in Miami and was Dade County’s largest employer at the time.

He was a low-key guy who would often skip the “crew parties” that were planned among his coworkers. He rarely visited the underground gay bars that existed in Miami at the time. Simpson had no family nearby. He came to Miami in 1951 from Louisville, Ky., for his career and his sexuality. For the most part, the gay community in Miami lived in obscurity, but if you were gay, you knew Miami was full of gay men.

On the evening of Aug. 2, 1954, Simpson landed at Miami International Airport after a final shift working aboard a flight from Detroit. For most of the flight, his colleague, fellow flight attendant Dorothy Hoover, remembered him having a giddy attitude, mentioning several times a date he had planned for that evening.

The Murder: A heinous crime

Simpson reportedly left his NW Fourth Avenue apartment around 10 p.m., according to his landlord, who was the last to see him. Two hours later, his body was found face-down in some gravel by Dick Cline and his girlfriend Joan at a spot near the Arch Creek Bridge, near NE 134th Street and Biscayne Boulevard.

Today, a Flanigan’s Bar & Grill marks the spot, but in the mid-1950s this area was a “lovers’ lane,” featuring a small, secluded beach area under the bridge where one could park a car right along the Little Arch Creek waterway and engage in sexual activity.

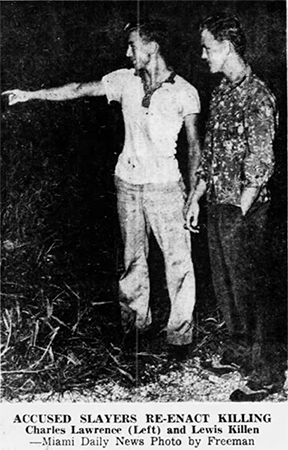

Simpson never made it to his date. It is believed that on the way there, he was propositioned by a young man named Charles Lawrence on the side of the road. Unknown to Simpson, Lawrence was notorious for “rolling” gay men (as local media called it then) — luring them to a secluded spot where his accomplice, Lewis Killen, would jump out and help rob the victim.

Usually, Killen would wait until Lawrence began engaging in sexual activity with the victim before attempting the robbery. Killen and Lawrence would not kill their victim, but in Simpson’s case, for reasons still not clear, something spooked Lawrence when Simpson didn’t cooperate like other victims had done.

Lawrence shot him in his left side and Simpson, stumbling out of the car yelling, “Leave me alone! Leave me alone!” finally tossed over his keys and wallet before collapsing a few yards away.

According to the North Miami police report, Lawrence and Killen made off with $25 and claimed they thought Simpson would live. They said they were surprised when they found out the next day that he had died.

The Reporting: Murder blamed on “gay drama”

Miami Daily News reporter Milt Sosin was on the story from the moment it broke. He wrote his first front-page article aptly titled “EAL [Eastern Airlines] Man is Slain on Lovers Lane” in the afternoon edition of the paper Aug. 3, 1954.

Along with the headline, there was a picture of the head of Simpson’s corpse.

Sosin suspected Simpson was gay because of the location in which the murder took place. Sosin referenced the potential killer as a man and suggested that it was possibly a sex crime.

The story immediately gained traction, but rather than trying to report on the heinous crime itself, Sosin instead focused on Simpson’s sexuality. At the time, homosexuality was rarely mentioned in mainstream media. Following the police investigation, Sosin learned that police felt they were busting a colony of maybe 30 gay men in the area, but he knew he had a major story when he learned that police actually discovered the area was actually home to about 500 gay men — much larger than they could have imagined.

The follow-up front-page story focused on Simpson’s sexuality, rather than the crime, in a story on Aug. 9, 1954, with the headline “Pervert Colony Uncovered In Simpson Slaying Probe.”

The article detailed that nearly 500 gay men conjugated in a northeastern part of downtown Miami around where the Omni Center is today. The article went on to further accuse Simpson of mixing with the wrong crowd and getting involved in “gay drama,” which it suggested might have been the motive behind his murder. One investigator quoted in the article even claimed the murder might have been because Simpson was looking to become “queen” of the colony.

The Trial: The gay-panic defense

There was no doubt about who committed the crime — Lawrence and Killen both admitted to the murder — but, even so, they played the gay-panic defense, testifying in November 1954 that, while they did like to “roll” gay men, Simpson took it too far. They claimed Simpson made them feel unsafe and made unwanted sexual advances towards Lawrence.

The jury appeared to be influenced by the fact that local newspapers alarmed them and the rest of the public about the activity that was going on.

The Miami Herald and Miami Daily News mostly ignored the trial, instead focusing on stories of homosexuality around the Miami community.

With the term “pervert” being used to describe Simpson in court, the jury might have also felt sympathetic to Lawrence’s claims.

Lawrence and Killen were eventually convicted of a lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Both men are alive today and in their 80s, living in Palm Beach County.

SFGN contacted both men by phone. Lawrence hung up after learning what the call regarded and Killen never returned the voicemail.

The Aftermath: The media warns community of the gays

Simpson’s murder was the catalyst of what quickly seemed liked endless homophobia in South Florida. Various Christian activist groups stepped up and called for Dade County politicians to rid the area of homosexuality by raiding known gay bars, clubs and hangout spots.

WTVJ ran a documentary warning people of the dangers of gay people in the mid-1960s. All three major area newspapers (The Miami Herald, Palm Beach Post and Ft. Lauderdale News) would run article after article throughout the ’60s informing readers to be aware of their neighborhood surroundings and who their neighbors might be, in the event that one was gay.

In response to this panic, the state of Florida set up the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (commonly known as the Johns Committee). This committee was responsible for distributing literature throughout the state warning citizens of gay activity. The committee also targeted, interrogated and stripped teachers of their credentials whom members suspected of being gay.

In the 1970s, singer and orange-juice spokeswoman Anita Bryant launched her now-infamous “Save Our Children” campaign in Miami-Dade county against the LGBT community — showing gay panic was still alive and well.

Graham Brunk, born and raised in South Florida, is a librarian in Palm Beach County and has an interest in local LGTBQ historic events.