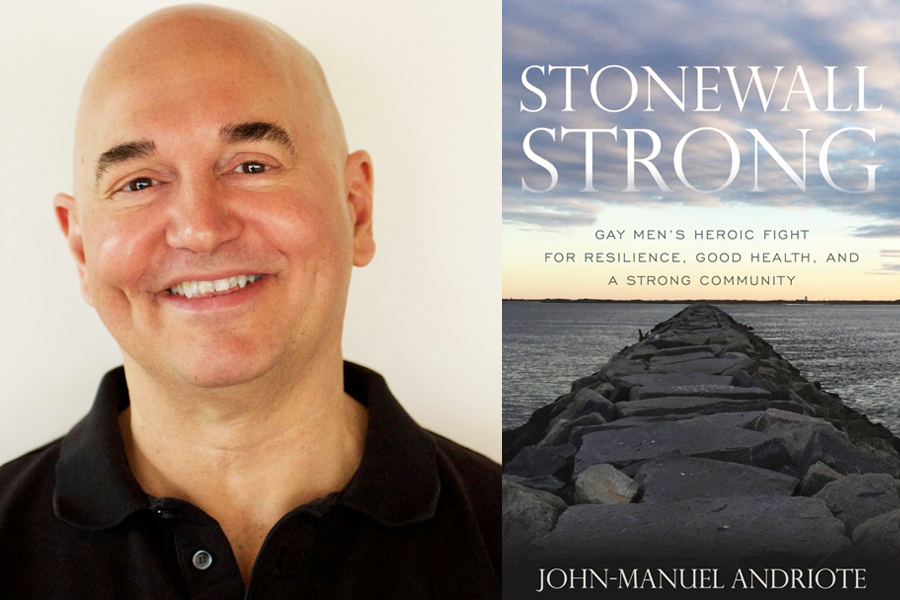

Below is an excerpt from “Stonewall Strong: Gay Men’s Heroic Fight for Resilience, Good Health and a Strong Community,” by John-Manuel Andriote. The book will publish Oct. 8 by Rowman & Littlefield; www.stonewallstrong.com.

In 1961, Frank Kameny and Washington, D.C., native Jack Nichols organized the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., an affiliate of Harry Hay’s original group in Los Angeles in name more than in style. Nichols had been deeply affected at age 15 when he read Edward Sagarin’s 1951 book “The Homosexual in America.” Nichols recounted decades later in a letter to “The Gay Metropolis” author Charles Kaiser that he was most touched by Sagarin’s quotation from the prominent African-American activist and author W. E. B. Du Bois: “The worst effect of slavery was to make the Negroes doubt themselves and share in the general contempt for black folk.” Nichols well understood the harmful effects of self-stigma in gay men’s lives.

Kameny and Nichols realized that one of the biggest obstacles to gay people’s progress in society was the psychiatric profession’s classification of homosexuality as a mental illness. In a 1964 speech to the New York Mattachine Society, Kameny said, “The entire homophile movement is going to stand or fall upon the question of whether homosexuality is a sickness, and upon our taking a firm stand on it.”

In March 1965, the D.C. group threw down the gauntlet to the psychiatric establishment whose scientifically dubious classification of homosexuality served, as needed, to justify discrimination against gay people. “The Mattachine Society of Washington,” read the group’s public statement, “takes the position that in the absence of valid evidence to the contrary, homosexuality is not a sickness, disturbance or other pathology in any sense, but is merely a preference, orientation or propensity, on par with, and not different in kind from, heterosexuality.”

On April 17, 1965, Kameny, together with other members of the Washington Mattachine Society and members of the lesbian group Daughters of Bilitis, launched the first gay and lesbian protest in front of the White House. Ten members picketed against Cuban and U.S. government repression of homosexuals in the first organized protest by gay people demanding equality. On July 4 of that year, Kameny and Nichols organized the first-annual Fourth of July pickets outside Independence Hall in Philadelphia. Their presence before America’s most hallowed building was intended to remind Americans that not all their fellow citizens were granted the equal justice under law promised in the Constitution, written and adopted right there.

Many of the new generation of activists who thrived on the energy of Stonewall after the 1969 riots looked at the Mattachine Society’s coat-and-tie, blouse-and-skirt politeness as an anachronism, a hangover of an earlier time. Wistful longing for a place “somewhere over the rainbow” was giving way to a new insistence on equality here and now. “We were going to smash that rainbow,” says Stonewall “veteran” and Philadelphia Gay News founder and publisher Mark Segal. “We didn’t have to go over anything or travel anywhere to get what we wanted.”

But it was the Mattachines who had been chipping away — bit by bit, year by year — at the very bedrock of legal and social homophobia. The Washington Mattachines had already made it clear in their 1965 declaration to the psychiatric profession that there would no longer be a market in the homosexual community for their “pseudo-scientific” views of homosexuality. In 1970, the executive committee of the National Association for Mental Health declared that homosexual relations between consenting adults should be decriminalized. The group’s San Francisco chapter adopted a resolution asserting, “Homosexuality can no longer be equated only with sickness, but may properly be considered a preference, orientation or propensity for certain kinds of life styles.” Braced by the affirmation, gay activists began to strike with vehement regularity at the American Psychiatric Association.

“Psychiatry is the enemy incarnate!” shouted Kameny, seizing the micro- phone as he and other gay-rights activists effectively took over the world’s most important gathering of psychiatrists during its prestigious Convocation of Fellows. The Mattachines may have been known for their button-down style of protest, but Kameny was no ordinary Mattachine. He was a man who believed with every fiber of his being that gay is good. “Psychiatry has waged a relentless war of extermination against us,” he told the assembled doctors. “You may take this as a declaration of war against you.”

The APA’s nomenclature and statistics committee met with a group of gay activists, including Bruce Voeller from the newly formed National Gay Task Force (NGTF), who presented the scientific evidence proving homosexuality was not a mental illness. The committee, headed by Robert Spitzer, prepared a background paper on homosexuality for the APA’s board. In it they defined the simple standard by which psychiatrists to this day determine mental illness: For a psychiatric condition to be considered a mental illness, it must either cause distress or impair an individual’s social functioning. “Clearly,” wrote Spitzer, “homosexuality, per se, does not meet the requirements for a psychiatric disorder since … many homosexuals are quite satisfied with their sexual orientation and demonstrate no generalized impairment in social effectiveness or functioning.” For the record, he noted, “the terms ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’ are not really psychiatric terms.”

Two years after Kameny declared war on psychiatry, the American Psychiatric Association’s board of trustees voted unanimously in December 1973 to remove homosexuality from the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual,” the bible of psychiatric disorders. The board acknowledged that “the unscientific inclusion of homosexuality per se in the list of mental disorders has been the ideological mainstay for denying civil rights” to homosexuals. For good measure, they called for the repeal of sodomy laws and for the passage of antidiscrimination measures to protect the rights of gay people. Ronald Bayer, co-director of Columbia University’s Center for the History and Ethics of Public Health, pointed out that the APA’s diagnostic change “deprived secular society … of the ideological justification of its discriminatory practices.”

At a time when physicians, including psychiatrists, were held in very high esteem, it was unheard of that the prestigious medical field could possibly include homosexuals. To prove otherwise, former New York City health-services director Dr. Howard J. Brown came out publicly as a gay man in October 1973. His announcement made the front page of the New York Times. He told the paper he decided to come out because times were changing. “You get to a point in your life where you want to leave a legacy,” he said. “In a sense, this can help free the generation that comes after us from the dreadful agony of secrecy, the constant need to hide.”

Brown capitalized on the publicity his coming-out generated by helping to found the NGTF on Oct. 16, 1973, which helped achieve the massive victory with the APA for gay people only two months later. He wrote in his 1976 memoir, “Familiar Faces, Hidden Lives”: “The gay activists who converged on Washington on Dec. 15, 1973, were the first group of patients in history to insist that they were not sick and to demand that the label be removed.” When the APA voted to de-pathologize homosexuality, Brown says, “Never in history had so many people been cured in so little time.”

Even before the APA’s 1973 decision, Dr. Richard Pillard had already become the first openly gay psychiatrist in America. Pillard had just turned 82 when I interviewed him for this book in October 2015. He recalled his own experience in psychoanalysis as a patient. He was married at the time and had three daughters. After four years of analysis, he realized he was a gay man and needed to find a male partner. He divorced his wife but remained, and remains, close to her and his three daughters. “I concluded I am a gay man,” he said, “and this is not a mental disorder.”

Besides knowing Howard Brown, another inspiration for the newly out Dr. Pillard was an invitation in the spring of 1970 from the Boston University student homophile league. Now he would know other openly gay people right there in his workplace. “Less than a year after Stonewall, the idea of coming out was becoming embedded in our psyches,” said Pillard. “I remember telling a colleague I was going to give a talk to the student homophile league, and he said, ‘My God, there’s a league of them?’”

Pillard said that coming out had immediate rewards. Best of all, he said, there were no more “dark secrets.” He thought a moment, then added, “That is gay liberation. Freedom from our own fear.”

John-Manuel Andriote has written about LGBT, HIV/AIDS and other health and medical subjects since the early 1980s. He is the author of “Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America”; “Hot Stuff: A Brief History of Disco/Dance Music”; “Tough Love: A Washington Reporter Finds Resilience, Ruin and Zombies in his ‘Other Connecticut’ Hometown”; and a “fable for kids ages 5-105” called “Wilhelmina Goes Wandering.” His articles have appeared in the Washington Post, The Atlantic, the Huffington Post and leading LGBT publications across America. Andriote regularly speaks at conferences and universities, is interviewed by print and broadcast media and has been an adjunct communications professor at Eastern Connecticut State University. For more information on “Stonewall Strong,” visit www.stonewallstrong.com.