Many things have been said and written about “Stonewall,” the historic confrontation in June 1969 after a police raid at the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia-run gay bar on Christopher Street in New York City’s Greenwich Village that ignited the Gay Revolution — and an incredible change in attitudes and feelings about queer people throughout the world.

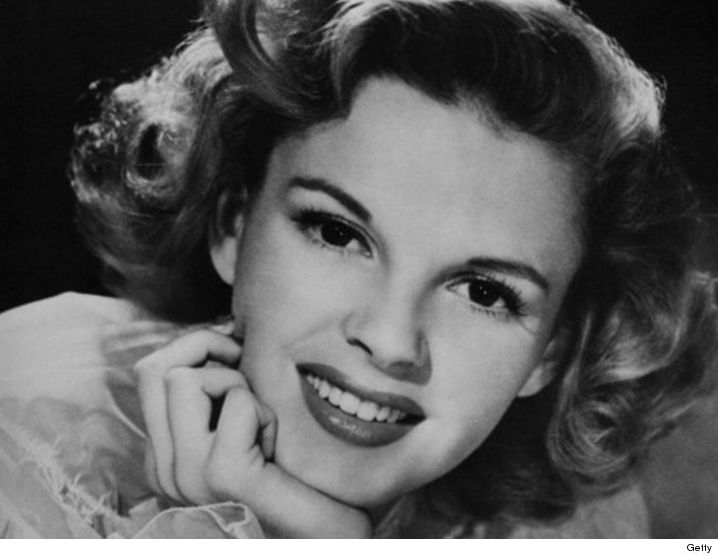

Among them, it happened on the night of a full moon, so a lot of the craziness on the streets can be blamed on that — not true. Another rumor is that it was all sparked by the death — and funeral, at Frank E. Campbell’s mortuary, uptown on Madison Avenue and 83rd, around the corner from the Metropolitan Museum — of gay icon Judy Garland. The “girls” were just so discombobulated by grief that they let go of all restraint and started breaking windows, uprooting parking meters (remember them?), throwing 40-pound garbage cans through the windows and even biting cops on the legs.

Again, no!

The Judy Garland myth, I’ve always felt, was the most pernicious of them all: Basically, it said that it took Garland’s death to make LGBT people angry enough to fight back. That was not true: We had been fighting back all along; there were numerous instances of us doing so against huge odds. Just a few were the melee at Cooper Donuts in L.A. in 1959; a 1965 action by San Francisco’s groundbreaking gay-friendly Council on Religion and the Homosexual when the cops tried to close down a drag ball the council sponsored to raise funds; also in 1965, the racially mixed “sit-in” at Dewey’s, an all-night coffee shop in Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square, after its management refused service to “masculine women and feminine men”; the famous and really brutal Compton’s Cafeteria riots in San Francisco in 1966; and the “Sip-in” in Julius’, an ostensibly straight bar in Greenwich Village, that same year.

People who were at Stonewall (and I was around the corner at another bar both nights, but came out for it on the second night) have all emphatically denied any Garland connection — including Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, a reliable witness; the late Jerry Hoose, who was later in the Gay Liberation Front; and David Carter in his well-researched book “Stonewall: the Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution.” I can certainly say that, in my own youth in that period, Garland was as far away from my mind as Uranus. Like most kids on their own in New York (I was 21 then), we were mostly centered on trying to survive in what was a much more contentious city. I describe New York in that period as a place of endless “class, race and ethnic resentment,” as well as knife-to-the-throat homophobia (police entrapment; regular violence and harassment on the streets; and, at work, intimidation and even blackmail) that was only slightly moderated by having enough money — i.e., those often-talked-about “rich queens” — that you could float along in some bubble above street level.

Power did not come from the streets then as we later felt, when gay groups joined other identity groups and seriously organized. What the Judy myth did was make many older, “bourgeois” gay men, lesbians and their allies feel comfortable. If what happened at Stonewall was outside their comfort zone — and for many it was — they could feel all gooey and happy knowing the “girls” were driven to this by some of the feelings they had: sadness over the death of Mickey Rooney’s girlfriend in those sweet 1930s musicals from their youth. As Mark Segal, publisher of PGN, said in a recent column about the Judy myth: “It trivializes the riot and our actions, especially those of the street kids and trans people.”

Trivializing us was a constant in that period: If queers did it, it had to be stupid, worthless or shallow. It could not come from any deeper feelings, and it certainly could not be born out of rage, anger, passion or honesty. It was certain we had none of these: We were the “decorative” elements of society that could be wiped away when mainstream power decided our presence was no longer worth it. So blaming a truly violent event of people standing up to the brute might of the New York City Police Department — with all its riot gear, tear gas, horses, squad cars, night sticks and guns — on the death, of all people, of Judy Garland … well, you could certainly gloat about that around cocktails on the Upper East Side. You could do a great, superior “Tsk, tsk” about it. But it was a lie.

Judy in her casket at Frank E. Campbell’s had nothing to do with Stonewall. We did.

Perry Brass’s 19 books include fiction, nonfiction, poetry, short stories and bestsellers like “The Manly Art of Seduction” and “King of Angels, A Novel About Childhood’s End and Sexual Awakening in Kennedy Era Savannah, Georgia.” His work often deals with the heartfelt feelings from his roots in New York’s Gay Liberation Front directly after the Stonewall uprising. He is a founding coordinator of the Rainbow Book Fair. Find more info at www.perrybrass.com.