America’s newest museum, Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, does something quite revolutionary: It recognizes the LGBT community as having played a part of that revolution. And it does so with several exhibits.

This may seem strange to point out, as LGBT people have been a part of every facet of life and war throughout history — and at times the major historical players, from Alexander the Great to World War II codebreaker Alan Turing. But up until now, you might have thought that LGBT people were invisible at the founding of the United States, and had no role in our country winning its independence. Thanks to this museum, that notion ends here and now.

In addition to lauding the community’s historical efforts, another of the museum’s themes is that the revolution continues; we still have work to do. As Dr. Philip Mead, the museum’s director of curatorial affairs and chief historian, states: “We’re so pleased to have a story of the American Revolution here that we hope includes all Americans and messages for people around the world.”

Here’s how LGBT media played a part in getting that story to the museum.

It’s a rare experience when you actually get to see something that you’re passionate about take root. It’s even more special when academics in the field run with that material, embrace it and make it a major point of their own project. What the museum has done is a great leap in LGBT history. Those involved are well aware of that and embrace it, maybe more than me. And I just love when those who join the march begin to lead it or add to it to create discussion.

So what has me so euphoric? It’s a story that goes back about six years. I was watching a TV talk show on which LGBT rights were being debated when a conservative on the panel stated something to the effect of, “When our founding fathers created this nation, they didn’t have those [LGBT] people in mind.”

Well, this angered me and, as you’d expect, became a challenge.

In response to that TV show, I pitched a project entitled “We Are America,” as part of the LGBT History Project I coordinate that appears in numerous newspapers around the country each October. We commissioned writers and began research on LGBT people who were instrumental to the cause of the Revolutionary War.

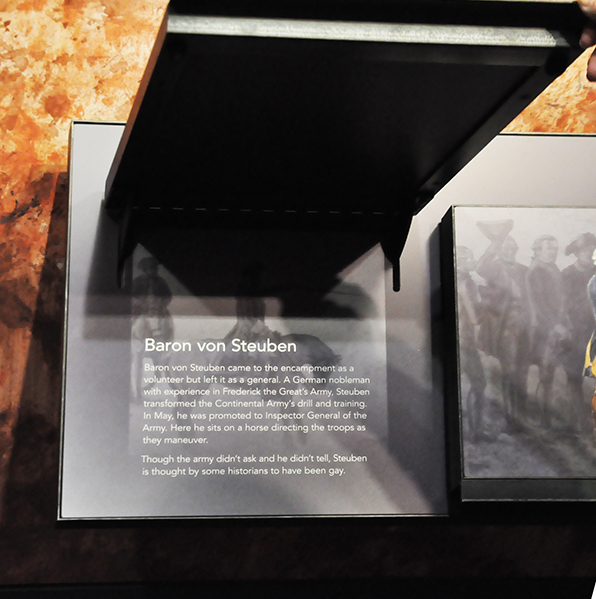

In our research, there was one character who stood out and fascinated me. His name was Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. He was a brilliant and somewhat flamboyant military genius. I read almost everything that I could find on the web and then the wonderful and revealing biography “The Drillmaster of Valley Forge.” The book was written by Paul Lockhart, who at this point most would say is the foremost expert on von Steuben and a teacher of military history. Von Steuben was outrageous and he was going to be my contribution to the project — never did I expect how passionate I’d become about him earning his rightful place in history.

Why von Steuben? Simply, his being acknowledged as a gay man would bring about major change in the way we look at the founding of this country. Without von Steuben, there would be no United States of America, and that means a gay man was a founding father. If we could prove that the founding fathers knew he was gay, then the founding fathers not only had us in mind when founding this country, but also expected us to have equality, or what could pass for equality at that time. Clearly, one of those equality points was the issue of gays in the military. For that is where von Steuben and founding father Benjamin Franklin come in.

Never did we expect that in our research we’d find such names touching on the subject as Washington, Jefferson, Franklin and Adams and many others. The project of explaining von Steuben’s impact became so big and touched on so many founding fathers that we had to break it into various segments: a piece on Franklin, another on Washington and so on.

Here in quick order is a short version of part of the von Steuben story:

In the late 1700s, von Steuben had a somewhat-celebrated military leadership career in the various German states, though at numerous times he was accused of having sex with his male recruits. He never denied the allegations, but did leave (escape) those countries before he could be charged or arrested. He arrived in Paris hoping to impress the Continental Congress’ ambassador to the Court of Louie XVI, Benjamin Franklin, and get a commission in the Continental Army commanded by George Washington. At the first meeting, Franklin was unimpressed. Von Steuben left Paris, but another scandal brought him back. Von Steuben and his friends — connected either to the court of Louie XVI or to Franklin — asked Franklin to have another meeting with von Steuben, knowing of those scandals and the chances that he could be arrested in Paris if he did not escape Europe.

Franklin met with von Steuben and agreed on the plan to escape, but not before von Steuben went shopping and enlisted an entourage. How could one not find him fascinating?

There can be little doubt here that Franklin, the Bill Gates of his day and a major celebrity in Paris at that time, with spies at his disposal, would not have known of von Steuben’s “problems.” This makes Franklin the father of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

Before von Steuben boarded his boat, he ordered fine, new special uniforms made with epaulets and medals, found a personal staff and, just to look like royalty, brought along a couple of dogs. He was then smuggled out of Paris on a ship that had munitions for the Continental Army, along with letters of introduction to Washington and Congress by Franklin.

The ship arrived in New England, and von Steuben met members of the Adams family and John Hancock before heading to meet Congress, and then on to Valley Forge to meet Washington.

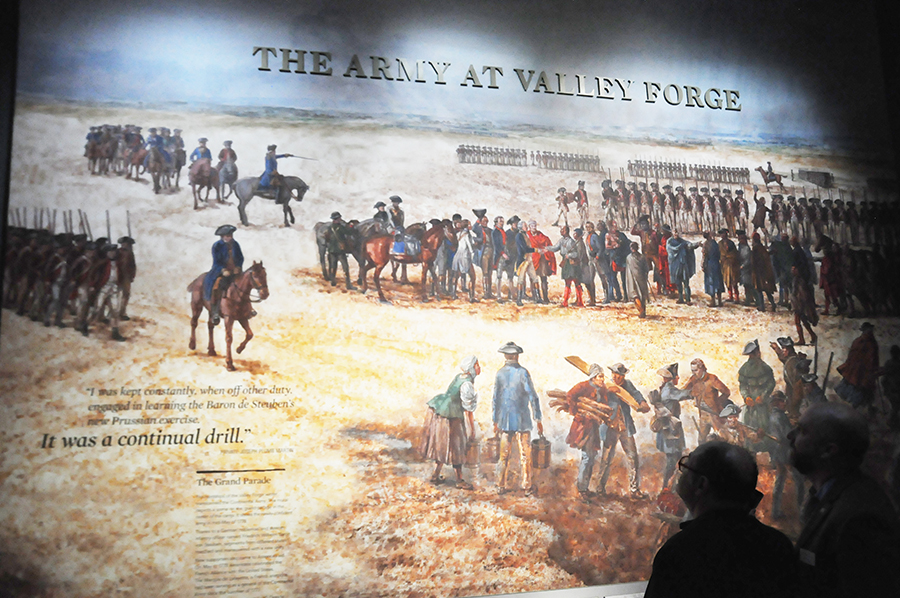

It was at Valley Forge that von Steuben pulled together Washington’s rag-tag Continental Army and began to make them into a cohesive, collective force. He taught them to drill, created a regulation book (which continued to be used by U.S. military until the war of 1812), instituted standards of sanitation and became Washington’s chief of staff.

Today, there are few, if any, professional historians who would doubt that von Steuben was gay. In our research, we unearthed correspondence among members of the Adams family regarding the subject. The whispers about von Steuben led the Continental Congress to delay granting him a pension, and it was Washington’s last act as commander of the Continental Army to write the Congress on behalf of von Steuben’s “moral character.” And finally, at the urging of Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury of the new country, Congress granted von Steuben an annual $2,500 pension.

According to the New York Public Library (“The Papers of von Steuben”), the following is a list of von Steuben’s major achievements:

February 1778: Arrives at Valley Forge to serve under Washington, having informed Congress of his desire for paid service after an initial volunteer trial period, a request with which Washington concurs.

March 1778: Begins tenure as inspector general, drilling troops according to established European military precepts.

1778-79: Writes “Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States,” which becomes a fundamental guide for the Continental Army and remains in active use through the War of 1812, published in over 70 editions.

1780-81: Serves as senior military officer in charge of troop and supply mobilization in Virginia.

1781: Replaced by Marquis de Lafayette as commander in Virginia.

1781-83: Continues to serve as Washington’s inspector general, and is active in improving discipline and streamlining administration in the army.

Spring 1783: Assists in formulating plans for the post-war American military.

Washington rewarded von Steuben with a house at Valley Forge (still in existence and open for visits), which he shared with his aide-de-camps, Capt. William North and Gen. Benjamin Walker. Walker lived with him through the remainder of his life, and von Steuben, who neither married nor denied any of the allegations of homosexuality, left his estate to North and Walker. His last will and testament, which includes the line “extraordinarily intense emotional relationship,” has been described as a love letter to Walker.

Von Steuben, like many LGBT people and their histories and contributions, has remained invisible or unrecognized until recently. That is what is so revolutionary about what the Museum of the American Revolution has done.

The largest original mural in the $150-million museum features von Steuben drilling the troops along with key figures at Valley Forge. Each figure has a biography. Here’s what the museum wrote about von Steuben: “Baron von Steuben came to the encampment as a volunteer but left it as a general. A German nobleman with experience in Frederick the Great’s Army, von Steuben transformed the Continental Army’s drill and training. In May, he was promoted to inspector general of the army. Here he sits on a horse directing the troops as they maneuver. Though the army didn’t ask, and he didn’t tell, von Steuben is thought by some historians to have been gay.”

On my recent visit to the museum, when Mead showed this to me, my response was, “What you’re going for is inclusion of the entire American family.” He smiled and responded, “Correct, the revolution belongs to all of us.”

He pointed out other LGBT exhibits.

One features a scene of two Quaker women visiting American prisoners of war at Independence Hall, then known as the Pennsylvania State House. The exhibit was based on the diary of a Quaker woman named Elizabeth Drinker, who wrote about the “two Hannah Catherells.”

“Now there’s ambiguity in this scene,” Mead noted. “It’s possible that this refers to a niece and an aunt who were both named Hannah Catherell in the Quaker community. It’s also possible that it refers to Hannah Catherell and Rebecca Jones, two women who lived together who were described at the time as ‘yolk mates.’”

When I inquired what “yolk mates” means, Mead explained, “They were coworkers, co-laborers in this place, in a school, for the good of the young people of Philadelphia. So some historians speculate that this may have been a same-sex couple. While we may not be able to prove that, we thought some of these displays were useful in getting people to think about the presence of the gay community here in Philadelphia in the 18th century.”

When I asked Dr. R. Scott Stephenson, the museum’s vice president of collections, exhibitions and programming, about the museum’s LGBT inclusion, he put it this way: “You can’t tell the story of E pluribus unum without the pluribus.”

Another possible LGBT connection exists in the Revolution Gallery.

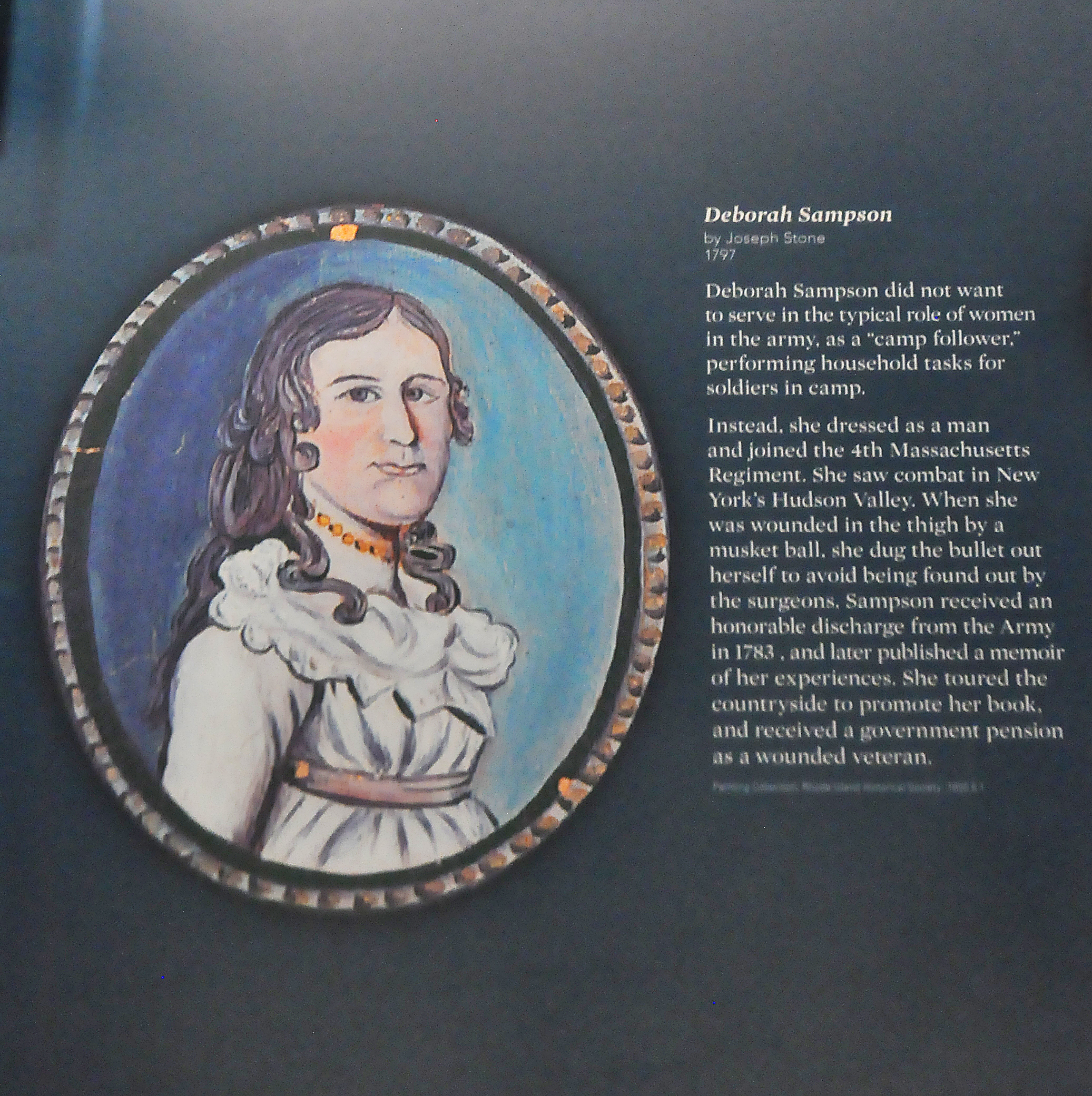

One of the people highlighted along a wall of revolutionaries is Deborah Sampson. A post-war, 1790s portrait depicting Sampson in a dress with a necklace and typical women’s haircut is featured alongside a summary of her contributions.

“You’ll learn here that, during the Revolutionary War, she dressed as a man to join the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment,” Mead explained. “She saw combat and was discovered after she was wounded. She was honorably discharged from the Continental Army on the basis of her gender and later published a memoir of her experiences, ‘The Female Review.’

“This is the place where we talk about the highest aspirations of the revolutionary generation in 1776,” Mead added about the gallery in which Sampson’s story is featured. “We talk about the limitations of the revolution in immediately expanding voting rights and other civil liberties of many groups. But our point here is that the revolution continues; it’s an idea, it’s ongoing. So while the 1760-90 period might not have seen major changes for all of these people, the ideas of the revolution made advancement possible. And along the way we meet people who have anticipation of those changes; they are pushing them forward with their own lives.

Mead next took me to the final screening room before you leave the museum for a film about the continuing revolution of our nation. The set-up features a clip of Abraham Lincoln and the words: “These revolutionaries were inspired and forged as a generation by their sacrifices and their belief that people have a right to liberty, equality and a role in governance.

“In 1858 Abraham Lincoln answers,” the narrator continued. “He sees a connection between the ideas of a revolution and the hopes of millions of immigrants arriving on U.S. shores. He describes these new arrivals as American revolutionaries, people without family ties to the revolution itself. He says that the revolution includes all people who are inspired by those words of 1776 and who look for the Declaration of Independence and feel they have a right to claim it. He called that the electric cord that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together.”

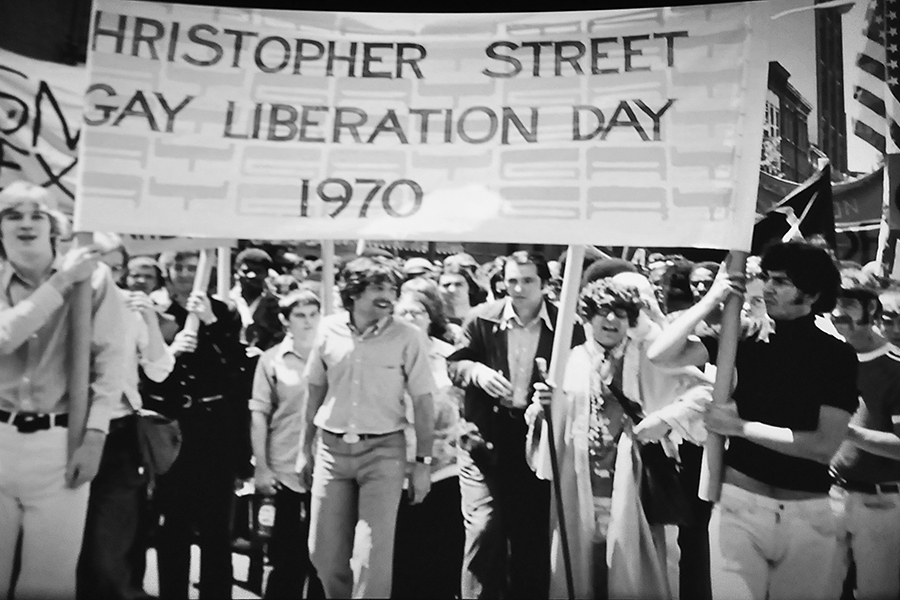

As these words played, we saw pictures of slaves winning their freedom, immigrants arriving at Ellis Island, laborers organizing, women fighting for the right to vote — and then a picture of the first Gay Pride March fill the entire screen. I cried.

For more information about the Museum of the American Revolution, visit www.amrevmuseum.org/.