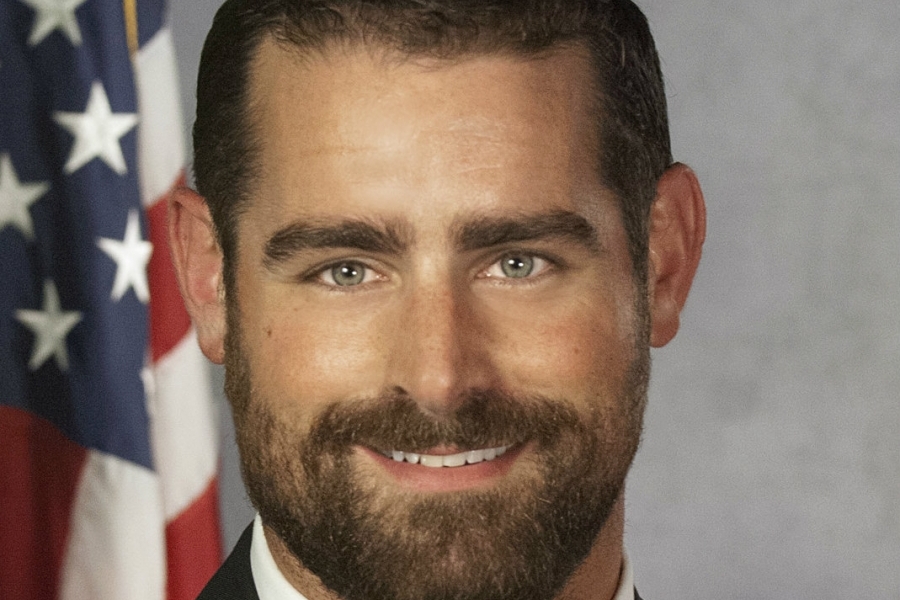

According to documents PGN exclusively obtained, a state commission is investigating Rep. Brian Sims following scrutiny about his travel reimbursements and speaking fees.

PGN obtained a copy of an Ethics Complaint Form from a source whose identity we are withholding. The individual filed the complaint with the State Ethics Commission, contending Sims, the first LGBT person elected to the state legislature, violated the state Ethics Act.

According to the Ethics Act, “No public official or public employee shall accept an honorarium.”

A March 31 letter from the Ethics Commission, signed by Executive Director Robert P. Caruso, that was given to PGN states: “The Investigative Division of the State Ethics Commission has initiated a full investigation in relation to the complaint” that the individual filed.

Caruso told PGN he was not permitted to comment on the investigation or the complaint.

“Confidentiality requirements in the law preclude me or any members of the commission or commission staff either confirming or denying the existence of an investigation or if we even received a complaint,” he said.

The complaint that individual filed listed five news stories published this past fall that raised questions about Sims’ travel reimbursements; a PGN story from October, entitled “Sims scrutinized for travel expenses and speaking fees,” was among the stories listed as evidence supporting the allegations. The media coverage stemmed from a City & State story, which was cited in the complaint; that report contended that “Sims failed to properly report thousands of dollars in travel reimbursements [in 2015] while collecting more than $42,000 in speaking fees since his election in 2012.” A sixth article outlined a speaking engagement Sims conducted at Penn State University about “his career as a legislator” and on his “current legislation before the House.”

“I would like an investigation to be conducted on all of his speaking engagements to ensure that there was no inappropriate acceptance of honoraria and no inappropriate content of his speeches,” the complaint read, noting that “inappropriate” referred to violations of the Ethics Act.

In a statement sent to PGN Wednesday, Sims said his “office learned recently that a complaint had been lodged against me, presumably for the civil rights and equality lecturing that I perform. Transparency and ethics have always been at the forefront of my work and every term I have served, I have sought and received advice from House legal counsel that my lectures are ethical and legal based on the State Ethics Commission’s 91-004 Baker Opinion and established precedent.”

The 1991 commission finding determined that then-state Sen. Earl Baker did not violate the state ethics law by accepting a $500 speaking fee. In a 4-3 decision, the commission found that “a senator who has degrees in political science, publishes works and speaks on subjects of political science is not prohibited from receiving a fee for speaking on the subject of legislative priorities for local government because such would be nonpublic occupational or professional in nature and not a honorarium.”

“I can’t stop my political opponents from wanting this to be an issue but the continuity of the work I began before taking office to foster understanding and tolerance is moral, legal and ethical,” Sims said. “It is the state’s duty to ensure the integrity of our government and a review of this work, and the transparency with which I’ve approached it, will make that clear.”

After the City & State story published last year, Sims issued a statement to the publication that the university speaking engagements he conducted were about his coming out and LGBT-rights work and were “not tied to my work as a legislator.”

Though declining to comment on this particular case, Caruso spoke to PGN about the general process for an Ethics Commission investigation.

He said the commission receives “roughly 500 complaints” each year and conducts a 60-day investigation on anywhere between 125-150 of the complaints. The investigation allows the commission to “establish if there is reasonable cause or reasonable belief that the complaint that was filed contains sufficient allegations that a certain public official violated the [Ethics Act].”

If there is enough evidence, the subject of the complaint will receive a target letter advising him or her about the complaint and that the commission is conducting an inquiry.

“If the commission determines there was a violation, they can direct the public official to remove themselves from the conflict,” Caruso said. “The commission can direct that the public official repay any amount of gain that they received.”

Caruso said investigations usually include interviews, subpoenas and review of financial documents.